‘Women Who Broke the Rules’ shares Coretta Scott King’s childhood

Leaders come from surprising places.

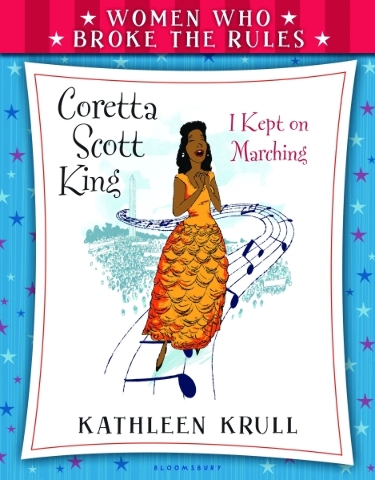

The quiet girl that sits the next row over may know how to inspire people. The know-it-all in your class could own a business in the future. The kid everybody picks on might become president. But in the new book “Women Who Broke the Rules: Coretta Scott King” by Kathleen Krull, illustrated by Laura Freeman, you’ll read about one woman who didn’t necessarily want to be a leader. She only wanted to sing.

Born in April 1927, Coretta Scott grew up on her family’s farm and was “a bit sheltered” as a girl; still, she was very aware that some things were unfair, which always made her angry. Everybody in Marion, Ala., knew Coretta was a fighter, that she had “the guts to climb up and over the Rules,” and that she had a temper, but there was one thing that calmed her: music.

Because her mother was the church pianist, Coretta was encouraged to sing solos as a very small child. She was known to rush through chores so she could spend time with her music. In high school, she was the school’s most promising singer-musician. Later, she landed a scholarship at an Ohio college, where she studied music and education, “in case a career in singing didn’t work out.” From there, she attended the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

Six months after arriving in Boston, she was introduced to a man named Martin.

At first, Coretta didn’t think much of Martin Luther King Jr. He wasn’t her type, and he was awfully outspoken. On the other hand, he spun dreams of a wonderful future. Their dates led her to a church, to a concert, dancing and eventually to marriage.

But being the wife of Martin Luther King Jr. wasn’t always a happy life. Coretta worried about Martin constantly, though she was proud of him. Their work together on boycotts was making change, but there was always danger. She could do what she needed to do, though — as long as she had her music.

I have to say that I was pleasantly surprised by “Women Who Broke the Rules: Coretta Scott King.”

So many biographies of King begin with her marriage to Martin, but Krull starts much earlier, putting an emphasis on Coretta Scott King’s lifelong love of music and her desire to have a career, despite the reality that women generally didn’t do that sort of thing then. That gives the story a tone of determination and quiet inspiration, a note that gets louder as the book progresses. I especially like that Krull writes at length of King as a child, which will resonate with young readers who likely won’t have any first-hand memories of this remarkable woman.

Don’t feel guilty for enjoying this book before you give it to your 9- to 12-year-old reader. It’s a quick and pleasant story you’ll both like; in fact, if she needs a biography to read this spring, you can put “Women Who Broke the Rules: Coretta Scott King” in the lead.

— View publishes Terri Schlichenmeyer’s reviews of books for children weekly.