Budding birdwatchers can tweet about ‘Birdology’

Somebody called you a birdbrain last week.

At first, it really made you mad. What kind of a thing is that to say? You’re way smarter than a bird and your brain’s much bigger, but what are you gonna do?

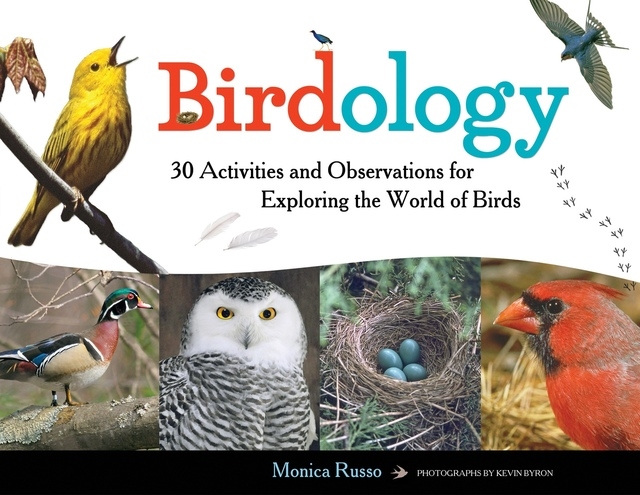

You’re going to read “Birdology” by Monica Russo, photographs by Kevin Byron, and next time someone says you’re a birdbrain, you’re going to say, “Thank you!”

No matter where you live — city or country, apartment or house — there are birds outside (and sometimes inside). There are, in fact, “at least” 9,000 different bird species in the world, and more than 700 species are found in North America. That makes bird watching an easy hobby for just about anywhere.

But what, exactly, are you watching for?

Let’s start with the bird’s body. Did you know that all birds have feathers? And did you know that birds are the only creatures with feathers (though some dinosaurs had them, too). Without feathers, a bird couldn’t fly or keep itself warm.

You might have heard the old saying that someone eats like a bird. That could be very interesting, because birds don’t have teeth. They do have beaks, however, and those beaks are specialized to help the bird eat its dinner of seeds, plants, bugs, fish or small animals. When a bird opens its beak to “speak up,” what it says could warn its flock of danger, remind others to stay away or tell you what kind of bird you’re hearing.

Even a bird’s feet can indicate a lot about its home and habitat. Ducks’ feet are wide and webbed, to make it easier to swim. Ruffled grouse have feet that help it walk on snow. Insect-eating birds have feet that can grasp twigs, while large birds — the ones that hunt for meat — have sharp talons at the end of their feet for capturing prey.

A hummingbird’s wingspan is around 3 inches, while the marabou stork’s wingspan is about 12 feet! Some birds build nests underground, while the nest of the Australian malleefowl is taller than you. Pigeons are non-native; they were imported from Europe. Sparrows came from Europe, Africa, Great Britain and Asia. And if you want to help birds, then volunteer — learn more inside this book!

So now who’s the birdbrain? Not your youngster. Not your curious future ornithologist, especially when you put “Birdology” in her hands.

From bird anatomy to habitat and volunteer opportunities, children will find a good overview of birds and bird watching in this book in terms that challenge them but won’t frustrate them. Russo and Byron don’t overwhelm their readers, but they do include activities, a glossary and resources; parents and grandparents will be happy to note that the authors urge a look-don’t-touch bird watching method, so kids can enjoy this hobby safely.

This is a great book for naturalists and bird watchers to share with a 7- to 12-year-old who wants to know what the feathered fuss is all about. Once you’ve got “Birdology,” you’ll both be singing its praises.

View publishes Terri Schlichenmeyer’s reviews of books for children and teens weekly.