Former sports writer shares first-person account of Ali and ‘Hurricane’ Carter

The first thing Muhammad Ali did as the limousine slowly crept away from the Passaic County Courthouse in Paterson, N.J., was reach into his pocket and take out a fistful of hundred-dollar bills. He placed the wad into one hand of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter while Carter nervously fingered the gold chain around his neck, which was clasped to a glittering gold medallion.

The medallion and chain had been given to Ali by officials in the Philippines when he beat Joe Frazier on a technical knockout after 14 rounds of the “Thrilla in Manila” on Oct. 1, 1975. Ali placed it around the neck of Carter “for good luck” before handing him the bundle of cash.

“I can’t take that from you, Muhammad. You’ve done so much for me already,” Carter said, referring to Ali’s role as co-chairman of the Carter-Artis Legal Defense Fund, which consisted of dozens of notables who raised money to help the one-time middleweight contender and John Artis, his co-defendant, get a new trial.

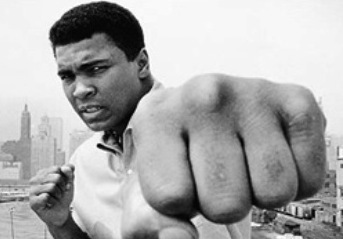

Three days earlier, on March 17, 1976, the New Jersey Supreme Court had unanimously overturned the triple-murder convictions of Carter and Artis. But now, as crowds lined the route, chanting, “Ali, Ali,” and “Hurricane, Hurricane,” Ali glared ferociously at Carter. He wrinkled his brow, then shot back, “You take it or I’m goin’ to punch you out. How do you expect to live? You ain’t got nothin.’ ”

Carter took the wad of bills and embraced Ali as a tear or two rolled down his face.

How do I know all this and so much more of what the man who died June 3 — indeed, the man who became known as “The Greatest” — did for Hurricane Carter over a period of years? I was the fly on the wall in that limousine.

It was late Saturday afternoon, March 20, and the limousine was the first in a motorcade of five, headed to the New York Hilton Midtown for a celebration, all of which was underwritten by the heavyweight champion.

In addition, during the brief court proceeding in Paterson that set Carter free, Ali added $5,000 to the $20,000 bail that had just been posted. Moreover, Ali pledged to bear personal responsibility for Carter, assuring the court that he would not leave the country.

And, at Ali’s request, Carter was granted permission by the court to travel to Marco Island, Fla., and stay at Ali’s palatial home while he prepared for his new trial.

At the conclusion of the court proceeding, Carter grabbed me firmly and led me past mobs of reporters and swarms of others who had gathered outside the courthouse and into the limo.

“You’re coming with us,” Ali said to me as he pushed me into the rear of the car. “Us” consisted of Ali, Carter and Brother James, who was Ali’s Muslim bodyguard.

I never did find out why the heavyweight champion of the world needed a bodyguard.

But I did get to know Ali fairly well during that period, especially before and during a Bob Dylan concert at Madison Square Garden on Dec. 8, 1975, attended by 20,000 to raise funds for the Carter-Artis defense. And earlier, on Oct. 17, 1975, when Ali led a parade of luminaries through the streets of Trenton — as more than 15,000 spectators watched — and to the capital office of then New Jersey Gov. Brendan Byrne, to request clemency for Carter and Artis.

I had spent more than a year digging out information that told me Carter’s first trial was filled with prosecutorial indiscretions. I visited him often in Trenton Prison, and I wrote numerous articles, up to the time the Supreme Court said in its decision, “We conclude that defendants’ right to a fair trial was substantially prejudiced so that the judgment of conviction must be vacated and a new trial ordered.”

In the March 22, 1976, edition of the Newark Star-Ledger, the newspaper I worked for at the time, I wrote the following of my exclusive interview with Ali on the Saturday evening of Carter’s release: “Certainly for Ali, who stretched back on the sofa of his 39th-floor (Hilton) suite as he spoke softly, the previous 36 hours were, as he put it, ‘hectic, real hectic.’

“Ali recalled the events as he stared at the ceiling. ‘I want to keep helping this man because he represents a whole lot to a whole lot of people — black people, white people, rich people, poor people, Christian people, Jewish people, Muslim people, all kinds of people. He represents the injustice suffered by all the other Rubin Carters and John Artises that are in the jails.’ ”

Herb Jaffe was an op-ed columnist and investigative reporter for most of his 39 years at the Star-Ledger of Newark, N.J. His most recent novel, “Double Play,” is now available. Contact him at hjaffe@cox.net.