The history of Cathedral Canyon: From dream to dust

If you close your eyes and listen, you can almost hear the ghosts.

The ghosts of a visionary landowner, a restless outlaw and a murdered man.

Or maybe it’s just the wind whistling through Cathedral Canyon, this dusty slice of Southern Nevada history carved into the desert outside Pahrump.

Visitors from all over the world once flocked to this unusual outdoor sanctuary, about 50 miles west of Las Vegas, to admire stained glass and other artwork set into the canyon’s walls, stroll a path that led to a pump-fed waterfall, gaze upon a towering statue of Jesus and stand before the grave of a once-wanted man whose bones are buried at the canyon’s edge. But time and vandals have since destroyed the place. Today, you’re likely to run into more tumbleweeds than tourists.

“What was once beautiful is now weird and eerie,” reads one of the few travel-site reviews of the canyon posted in recent years. “Don’t go,” reads another, “it’s upsetting.”

Interest in the offbeat spiritual site dwindled after the man who built and maintained it, former Las Vegas attorney Roland Wiley, died in 1994. In the ensuing years, the neglected canyon largely faded back into obscurity.

Then came the morning of Aug. 1, 2021. Just after sunrise, a distraught man who had been sleeping in his car nearby called 911.

He’d just seen two men in the canyon, he said. They were standing over a body.

Wiley, a one-time Clark County district attorney and two-time Nevada gubernatorial candidate, said he first had a vision for Cathedral Canyon while suffering from a bad case of tularemia, better known as rabbit fever.

In other accounts, he said the idea to transform the small box canyon about a mile off Tecopa Road into an open-air cathedral came to him while he was exploring the ruins of ancient churches destroyed by earthquakes in Antigua, Guatemala.

“I saw the crumbled walls of the cathedrals with statues sticking out in the ruins,” Wiley told the Review-Journal in 1982. “Those cathedral walls reminded me of the fallen banks at the canyon.”

Wiley had come to Las Vegas in 1929 to launch what became a lucrative law career. He bought the roughly 14,000-acre Pahrump Valley ranch on which the canyon sat in 1936. The young attorney, a tall, self-described Iowa farm boy, fell in love with the land that straddled the Nevada-California border.

“My goodness, there’s no place like it,” he said in a 1988 interview for the Nye County Town History Project, extolling the ranch’s mesas, ravines, benchlands, box canyons and “countless little hills (of) all different shapes and sizes.”

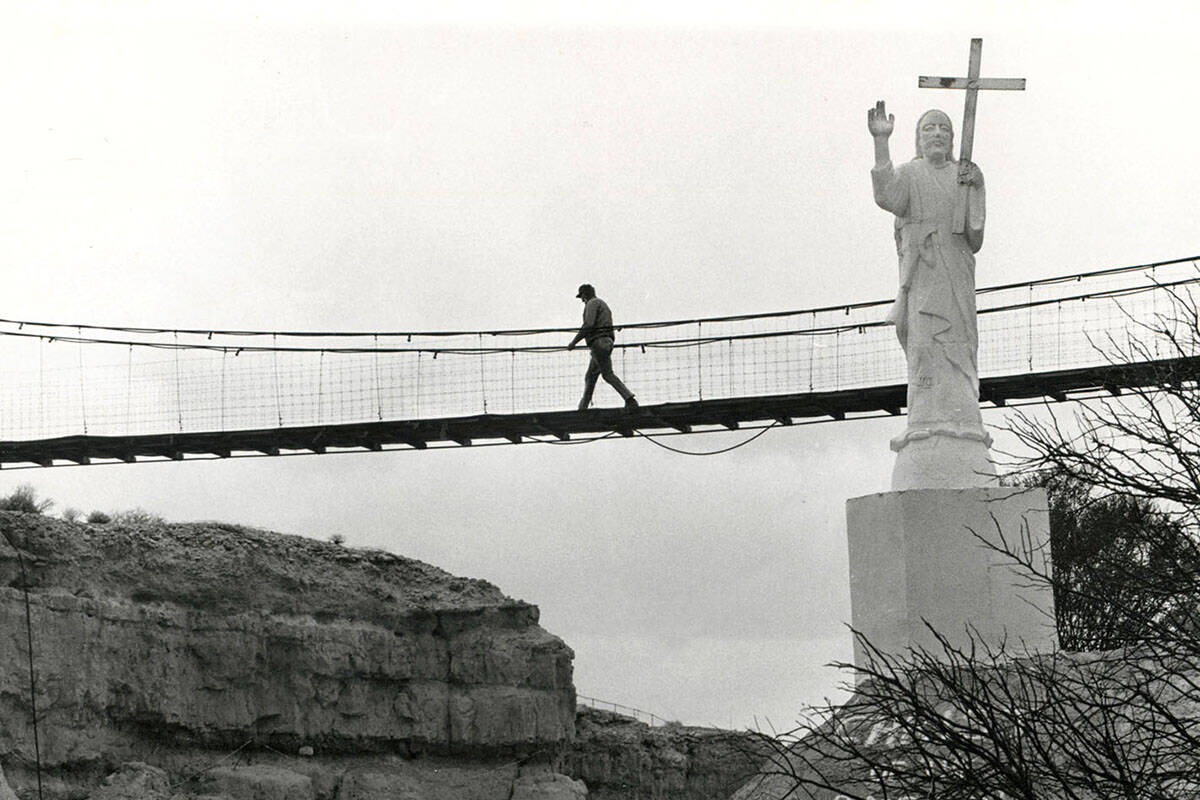

Wiley began work on his peculiar passion project in 1972. The first thing he built was a suspension bridge that spanned Cathedral Canyon’s approximately 100-foot width. He added a staircase leading from the top of the ravine to its floor, 50 or so feet below, along with sound and lighting systems and even bathrooms. Statues and placards containing poems and inspirational quotes from the likes of Abraham Lincoln and Albert Einstein lined the path at the bottom of the canyon. At the top, Wiley posted a message he’d written himself.

“It is my hope that this cathedral under the skies will give to you a set of new eyes,” the sign read in part, “and a whole new way of seeing things.”

Wiley threw open the canyon’s figurative doors and welcomed anyone who cared to visit. And plenty of people did. In its heyday, the “multi-denominational” church drew as many as 4,000 visitors a month. The site hosted church services, Easter egg hunts, art shows, trail rides, at least one wedding and a rock concert. People even showed up to spread the ashes of their deceased loved ones.

“It was a big deal back then,” says Arlette Ledbetter, who first visited the canyon with her sister, Debbie Scott, shortly after they moved to Las Vegas in the early 1970s. The then-teenagers were awestruck by what they saw.

“There were poems and statues in rock cubbies, one after another,” says Scott, now a semi-retired craps dealer in Pahrump. “You would come across one treasure after another.”

Ledbetter, who now serves as Pahrump’s tourism director, remembers the canyon filling her with wonder. “It was so beautiful — that natural rock setting. It was an intensely spiritual moment.”

Scott visited the canyon again after her brother died in a 1978 car accident. “I took my mom out there. It was a comforting, peaceful place.”

One of the first poems the two women came across in the canyon that day was “Immortality,” Clare Harner’s 1934 work about bereavement. The poem’s famous first stanza reads: “Do not stand/By my grave, and weep,/I am not there,/I do not sleep.”

Scott’s mother “carried that poem home in her wallet” after her brother died, she says.

“It made that a very special moment.”

Cathedral Canyon drew all types of people, from church groups to motorcycle gangs, Wiley said in a 1991 Review-Journal interview. He was proud that visitors respected the site even when nobody else was around.

“I’ve got a lot of nice things in here and nobody molests them at all.”

Wiley kept the unorthodox oasis open 24 hours a day and never charged an admission fee. Those who came after dark could turn on the lights themselves by flipping a switch. Wiley recommended visiting at night, when the illuminated canyon shone like a beacon in the blackened desert.

By the time Wiley landed in Las Vegas, an alleged murderer named Queho had been hiding out for years in the nearby canyons cut by the Colorado River.

Authorities linked the man, known to take odd jobs in Eldorado Canyon mining camps, to six or seven area killings between 1910 and 1919, including the shooting death of a watchman at the Gold Bug Mine. But over the next two decades, Queho, a Native American believed to have been born in the 1880s, became the scapegoat for nearly every murder committed in remote area locations.

“I’ve seen accounts that say he killed at least 26 people,” says historian Mark Hall-Patton, the retired administrator of the Clark County Museum.

Despite his legendary outlaw status, Queho lived on for more than a decade after 1919 “without killing anyone that we find any record of,” Hall-Patton says. “He was a killer, but not by any means as prolific a one as has been attributed to him.”

Queho managed to evade every posse assembled to apprehend him, outsmarting law enforcement officials until February, 1940, when prospectors found his mummified remains in an arid cave high above the Colorado. Along with him, they found a badge that once belonged to the watchman at the Gold Bug Mine.

An unseemly squabble ensued over Queho’s remains, which passed through a number of different hands and were even put on display for years in a replica cave at the Las Vegas Elks Club’s Helldorado Village. What was left of Queho “would get stolen and be found again and go back and forth,” Hall-Patton says. “It was not a particularly nice way of handling them.”

Finally, in the mid-1970s, an unlikely interceder acquired the man’s remains. Roland Wiley bought the bones and then buried them near the entrance to his beloved Cathedral Canyon. “Roland said, ‘No, this is wrong, this guy should be buried,’” Hall-Patton says. “Which is both wonderful because he was finally buried and sort of unfortunate because it’s nowhere that Queho ever was.”

Queho’s name appears misspelled on the concrete tombstone over his grave, and his death date is erroneously listed as 1919. Though Wiley got the details wrong, at least “he tried to honor (Queho) and give him a place where he could be out in nature,” Hall-Patton says. Today, the unusual gravesite is the best preserved of Cathedral Canyon’s few remaining artifacts. Situated not far from the canyon’s entrance, it overlooks an old airstrip Wiley built to speed up his weekend commutes from Las Vegas. Beyond that is miles of empty desert.

It’s a midsummer morning, already blazing but not brutal enough to keep me indoors. A friend and I decide to visit Cathedral Canyon. After heading west from Las Vegas on state Route 160 for about half an hour, we take a left on Tecopa Road. From there, it’s about five miles to the marked turnoff to the canyon, which lies across the road from a historical monument to the Old Spanish Trail. We take the potholed turnoff to the right and, a few minutes later, reach two stacked tractor tires that mark the canyon’s edge. We find the site empty, quiet and bathed in golden morning light. The purple Spring Mountains lie in the distance beneath a brilliant blue sky.

The picturesque scene reminds me of something Wiley told the Review-Journal years ago: “There’s no monotony in the desert. The colors and contours are always changing.” It feels peaceful here at first, serene. But soon after entering the torn-up canyon, a different feeling begins to take hold.

Gone are the statues, save the 20-foot Christ of the Andes, whose head looks to have been shot off. Gone is most of the artwork and all of the stained glass. Gone are the placards, the benches, the waterfall, suspension bridge and even the toilets. Gone is most of Cathedral Canyon’s former charm.

But the site has not simply been left alone, over the course of the nearly three decades since Wiley died, to be reclaimed by the desert or returned to its once-natural beauty. Instead, its walls have been sprayed with graffiti. Broken liquor bottles, bullet casings and empty cans of spray paint litter its floor. Rebar stakes jut from the side of the canyon where a staircase once stood. In one area sit the remains of a campfire, half a pizza box and an old can of soup covered in flies. A sour smell wafts through the air. The place has been destroyed.

My friend and I can’t help but wonder exactly where, a couple of years before, the body was found.

It happened early on that other summer morning, a Sunday in 2021. The man who had been sleeping in his car nearby said he came upon two men standing over a bloody body, later identified to be that of 27-year-old Roy Jaggers.

“The one gentleman who stood closest to the body seemed proud of what he done,” the witness later testified, according to the Review-Journal. “He smiled at me, like he did something good.”

Police soon arrested Las Vegas resident Heather Pate, then 27; her boyfriend, then-36-year-old Kevin Dent; and her former boyfriend, Brad Mehn, then 37, in connection with Jaggers’ gruesome murder.

Officials alleged that Pate — who was Jaggers’ neighbor — and Dent had kidnapped the Las Vegas man and taken him to Nye County, where they met Mehn. The three then tortured Jaggers with various tools and weapons for hours, police said, before taking him to Cathedral Canyon. There, Jaggers was forced to walk off a cliff before Mehn shot him multiple times, prosecutors said.

The Review-Journal reported that, according to prosecutors, Pate and Dent believed that Jaggers, who often babysat for Pate, had harmed one of her children. But during closing arguments at Mehn’s trial, prosecutors accused him of taking Pate’s word about Jaggers “without any evidence.”

In April 2023, Pate pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and first-degree kidnapping charges, while Dent pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. They were sentenced in July to life in prison with the possibility of parole. A jury in May convicted Mehn on first-degree murder and kidnapping charges and sentenced him to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Visiting the canyon two years after Jaggers’ death, I find it impossible not to think about the moment that turned Wiley’s cathedral into a crime scene. Indeed, I first learned of the canyon’s existence through news stories about the murder that had taken place at a “former roadside attraction” in the desert outside Pahrump.

As the sun and temperature continue to rise, my friend and I make our way back to the top of Cathedral Canyon. Shortly before leaving the site, I stand at the edge and gaze down at the ruins, thinking about dreams and how they die.

On August 15, 1994, Roland Wiley died at age 90. Days later, his widow, Mary Wiley, told the Review-Journal that Cathedral Canyon would be preserved.

“He loved that canyon,” she said.

Wiley’s family reportedly hired a man in his 80s to take care of the site, but it quickly fell into disrepair. At least one community effort to restore the canyon failed as would-be preservationists were unable to secure permission from Wiley’s family to proceed, the then-director of the Pahrump Valley Chamber of Commerce told the Review-Journal in 1999.

By that summer, the canyon’s suspension bridge had been barricaded and “No Trespassing” signs had been posted. (No such signs were visible the day I visited, decades later.) “It was not considered safe to go out there,” Steven Scow, an attorney who represented the Wiley family, told the Review-Journal in 1999.

As the years rolled by, the canyon continued to deteriorate. Vandals tagged and trashed the place. Fewer tourists visited. Wiley had intended Cathedral Canyon to be “a gift to the community, to anyone who wanted to go out there,” Hall-Patton says. “He saw it as a free folk art environment, and it really was. … I’m never happy seeing the past destroyed like that.”

The site mostly disappeared from headlines until that disturbing morning in 2021.

“Realistically,” Hall-Patton says, “I don’t think anything can be saved.” Still, he would like to see “some kind of marker” at the site to indicate “what the place once was.” He says the local chapter of E Clampus Vitus, a fraternal historical organization to which he belongs, would be thrilled to install a historical marker, with the landowner’s permission. Without one, “it just looks like it’s been trashed, so why not trash it more.”

In July, 2023, Scow confirmed via email that he represents Cathedral Canyon’s current owner and declined to comment on the landowner’s behalf. Scow didn’t respond to a follow-up message asking him to confirm whether the canyon was still owned by a relative of Roland and Mary Wiley.

As of this writing, the canyon still appears on the Pahrump Valley Chamber of Commerce’s website along with other “things to do” in the area. (The chamber’s CEO did not respond to a request for comment.)

“Despite the fact that the canyon is now in ruins,” the site’s description says, “its spirit is untouched, and the peacefulness of the canyon is undeniable.”

Roland Wiley’s grave lies beside that of his wife in the shade of an enormous pine tree on a gentle slope in a downtown Las Vegas cemetery. Sunrise Mountain rises from the valley floor in the east. Water splashes in a nearby fountain.

On an unseasonably cool morning in early August, street sweepers make their way down Main Street, just outside the cemetery, where the neighborhood’s homeless inhabitants huddle with their belongings along the sidewalks between shelters.

A couple of gravediggers work beneath a sky soupy with rainclouds and smoke that has drifted into the valley from a wildfire burning in the desert near Searchlight.

Engraved on the flat headstone that marks Roland Wiley’s final resting place are the following words: “Blessed are those who dream dreams, and make them come true.” ◆