Mormon leaders call for end to racism, protest violence

SALT LAKE CITY — Top leaders from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints urged members Saturday to root out racism and make the faith an “oasis of unity” while also decrying violence at recent racial injustice protests they said amounted to “anarchy.”

A church leader also offered guidance ahead of next month’s presidential election: Peacefully accept the results.

The election advice from Dallin H. Oaks, the second-highest-ranking leader of the faith, came after President Donald Trump has refused to commit to accepting November’s results and tries to sow doubts about the voting process.

Oaks didn’t mention Trump by name, but referenced teachings from church founder Joseph Smith for members to follow laws where they live.

“It means that we obey the current law and use peaceful means to change it. It also means that we peacefully accept the results of elections,” Oaks said. “We will not participate in the violence threatened by those disappointed with the outcome. In a democratic society, we always have the opportunity and the duty to persist peacefully until the next election.”

In the same sweeping speech at the signature conference of the faith known widely as the Mormon church, Oaks said peaceful protests are protected by the U.S. Constitution but spoke out forcefully against actions at recent rallies that he said go beyond what is protected by law.

“Protesters have no right to destroy, deface or steal property or to undermine the government’s legitimate police powers,” said Oaks, a former Utah Supreme Court justice. “The Constitution and laws contain no invitation to revolution or anarchy.”

The speech was delivered at a conference being held in Salt Lake City without attendees because of the pandemic and when many members are living through a reckoning over racial injustice, especially in the U.S. following the May police killing of Black man George Floyd.

Oaks tried to strike a balance between preaching unity and obedience to the faith’s 16.6 million adherents worldwide. He called on members to help root out racism against people of all cultures.

“This country should be better in eliminating racism, not only against Black Americans … but also against Latinos, Asians and other groups,” Oaks said. “This nation’s history of racism is not a happy one and we must do better.”

Fellow church leader Quentin L. Cook, also a member of a top governing panel called the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, made a similar plea for the religion to become a big tent for people of all racial and cultural backgrounds.

“With our all-inclusive doctrine, we can be an oasis of unity and celebrate diversity,” Cook said.

Neither Oaks nor Cooks mentioned the church’s past ban on Black men in the lay priesthood, a prohibition rooted in the belief that black skin was a curse. The ban stood until 1978 and lingers as one of the most sensitive topics in the faith’s history.

The church disavowed the ban and the reasons behind it in a 2013 essay — explaining that it was enacted during an era of great racial divide that influenced the church’s early teachings. But the church has never issued a formal apology for the ban, a sore spot for some members.

The Utah-based religion doesn’t provide ethnic or racial breakdowns of its members, but scholars say Black members make up a small portion of followers.

Members of African descent account for at least 8 percent of Latter-day Saints globally while African-Americans likely make up 3-5 percent of U.S. members, according to Matt Martinich, a church member who analyzes its numbers with the nonprofit Cumorah Foundation.

Estimating how many members are Latino or Asian is much more difficult, Martinich said.

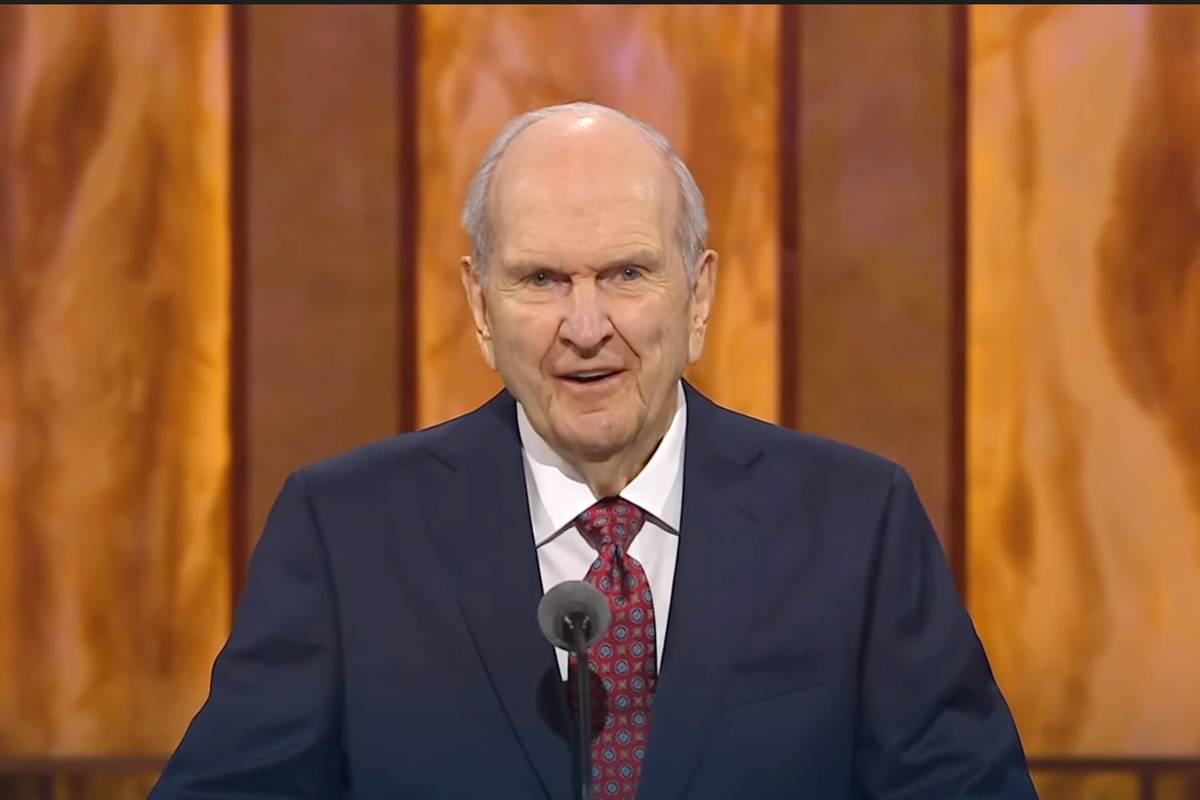

The pleas for unity echoed messaging from church President Russell M. Nelson who, since taking over in 2018, has preached racial harmony and mutual respect. Nelson has launched a formal partnership with the NAACP.

The church grew more diverse in 2018 when it selected to the previously all-white Quorum of the Twelve the first-ever Latin American apostle, Ulisses Soares, and the first-ever apostle of Asian ancestry, Gerrit W. Gong. There are still no Black men on the panel.

Second conference with no audience

Saturday’s conference is the second one held this year without an audience. In April, a similar event marked the first time since World War II that the conference was held without attendees.

The faith’s top leaders sat 6 feet apart on a stage alongside floral arrangements. They wore masks when they weren’t speaking, each sitting in elegant dark red chairs. Many of the leaders are older than 70, including the 96-year-old Nelson.

Gong was not there alongside fellow leaders because he might have been exposed to the coronavirus and stayed home, church officials said. His speech was prerecorded.

The conference normally attracts some 100,000 people to the church conference center in Salt Lake City.

Addressing the pandemic, church leaders said it will help people grow spiritually.

“We are here on earth to be tested, to see if we will choose to follow Jesus Christ, to repent regularly, to learn, and to progress,” Nelson said.

In his comments about politics, Oaks preached civility but followed long-standing precedence for church leaders to remain politically neutral.

He spoke on the same day that Kamala Harris — the running mate of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden — toured a church history site in Salt Lake City after landing in the state ahead of Wednesday’s vice-presidential debate at the University of Utah.

“In a democratic government we will always have differences over proposed candidates and policies,” Oaks said. “However, as followers of Christ we must forego the anger and hatred with which political choices are debated or denounced in many settings.”

While church leaders sometimes weigh in about what they consider crucial moral issues, they are careful not to endorse candidates or parties. Church members have historically leaned heavily Republican, but the GOP’s grip on the faith’s voters has slipped slightly under President Donald Trump, according to the Pew Research Center.

During the 2016 presidential election, the church defended religious liberty after Trump suggested banning Muslims from entering the U.S.

Church leader Patrick Kearon made a brief mention of the current political climate in the conference’s opening prayer when he said, “We yearn for a return to grace, dignity and civility in public life.”