Report ranks Nevada last in health care for kids

When it comes to providing health care for children, Nevada is sick, a new national health report has found.

To illustrate: If Nevada improved its child health care performance to the rate of Iowa — the top state when it comes to preventive care visits — 161,540 more children up to age 17 in the Silver State would receive both routine and preventive medical and dental care visits each year.

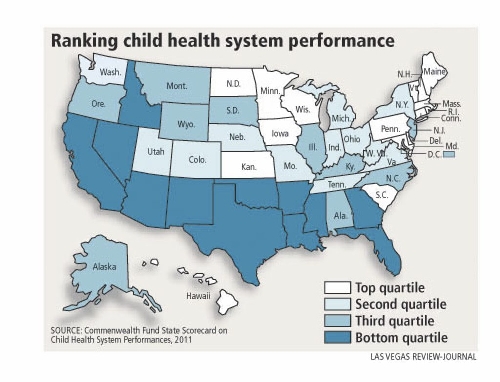

The report, issued today by the Commonwealth Fund, ranked Nevada last — behind 49 states and the District of Columbia — on its "State Scorecard on Child Health System Performance."

A physician, Dr. Edward L. Schor, and four researchers compiled the study.

The scorecard examines state performance on 20 key health system indicators for children within the broad areas of access and affordability, prevention and treatment, and potential to lead healthy lives. Nevada ranked 48th in access, dead last in prevention and 43rd in potential to living healthy lives in the future.

The Commonwealth Fund, a private foundation with bases in New York City and Washington, D.C., was founded by philanthropist Anna M. Harkness in 1918 with the broad charge to enhance the common good. It supports independent research on health care issues.

"This report needs to be a wake-up call to the public and private sector. We need to work together," said Dr. Mitchell Forman, president of the Clark County Medical Society.

"The very young, along with the elderly are the most vulnerable among us. … One thing is sure: Cutting Medicaid reimbursement rates now is the wrong thing to do."

In his recent State of the State address Gov. Brian Sandoval proposed cutting reimbursement rates to physicians who see Medicaid patients by 15 percent. More than 275,000 Nevadans are already enrolled in the free health care program for the poor, disabled, handicapped and elderly. As the recession continues, the number is increasing by 3,000 to 4,000 a month.

Doctors already say the reimbursements for seeing Medicaid patients don’t cover their costs, and many opt out of the program.

The Commonwealth Fund report noted that until 2000 the number of uninsured children in the nation rose rapidly "as the levels of employer-sponsored family coverage eroded for low- and middle-income families." The trend, the report points out, was reversed across the nation as a result of Medicaid expansion and the renewal of the Children’s Health Insurance Program, known in the Silver State as Nevada Check Up.

Currently, the report said, public programs such as Medicaid and Nevada Check Up fund more than one-third of health care for all children nationally.

More cuts to Medicaid reimbursement, said Dr. Ron Kline, president of the Nevada State Medical Association, will "basically guarantee" that fewer physicians see Medicaid patients, cutting down health care access even more to poor children.

"You’ll actually see people using emergency rooms, the most expensive way to deliver health care, far more than they do now for their children’s health care," Forman said.

According to the report, only 45 percent of Nevada children have a "medical home," its term for the medical practitioners who they see regularly. By comparison, in the best state, New Hampshire, the number is nearly 70 percent.

Dr. Tracy Green, the Nevada State Health Officer, said Tuesday that unlike many states, Nevada has a severe shortage of doctors. In 2007, the last year with firm statistics, the state had 218 physicians per 100,000 residents, ranking 48th among states in the number of physicians per capita.

"We’re planning school-based health centers throughout the state to improve access," she said. "In rural areas, we’re very short of doctors."

Green said she hopes to attract more foreign doctors to the state through the J-1 visa waiver program. The program allows foreign medical graduates who have completed graduate medical training in the United States to remain and work in under served, often rural, areas.

According to the report, 83.4 percent of Nevada children ages 0-18 were insured either through public or private programs, more than 10 percent less than the best state, Massachusetts, which has nearly 97 percent of children covered by insurance.

"The good news," Kline said, "is that the vast majority of our children are covered. The difference isn’t that great."

For children up to age 6 in a Nevada family of four to qualify for Medicaid-based health care, the family must not make more than $2,444 a month, state officials said. Once the children are over 6, the family cannot make more than $1,838 per month.

For children in a family of four to qualify for Nevada Check Up-based health care, the family can make no more than $3,675 a month. In many states, according to Miki Allard, a staff specialist with the state division of welfare and supportive services, a family can make much more money and still have children on public health programs.

People have to decide, Forman said, whether they want health care for children to be a priority.

"You have to remember," Kline said, "that we have a lot of employers in Nevada who don’t offer health insurance, but who pay wages that are too high to parents for their children to be covered by public programs."

Green pointed out that the state has programs in place to ensure that all Nevada children, even if they don’t have financial means, can be vaccinated. Yet the report stated that only 65 percent of young children up to 35 months received all their vaccinations, ranking the state 46.

"Too many people aren’t aware of our programs," she said. "We have to get the word out, for example, that the Southern Nevada Health District offers such programs."

More than 30 percent of Nevada children have oral health problems, according to the report, ranking the state 49th in a section of the report regarding future oral health.

Also in that "future" section was the problem of obesity, where 34 percent of Nevada children aged 10 to 17 were obese, ranking the state 41st.

"Children need to be taught in school at a very early age in health classes what a good food and bad food is," said Dr. Ivan Goldsmith, an internist who runs the TrimCare weight management program in Las Vegas. "They need to be shown what a good diet is, what proper nutrition and exercise are, so they can live long lives. Then they can go home and help mom and dad with the shopping."

Green, while optimistic that the state can do better in bringing health care to children, is also realistic.

"It’s not going to be easy when we have the budget constraints we have now," she said.

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.