Pandemic fatigue: Coping with COVID-19’s mental toll

The social butterfly had his wings clipped.

That’s what it felt like, anyway.

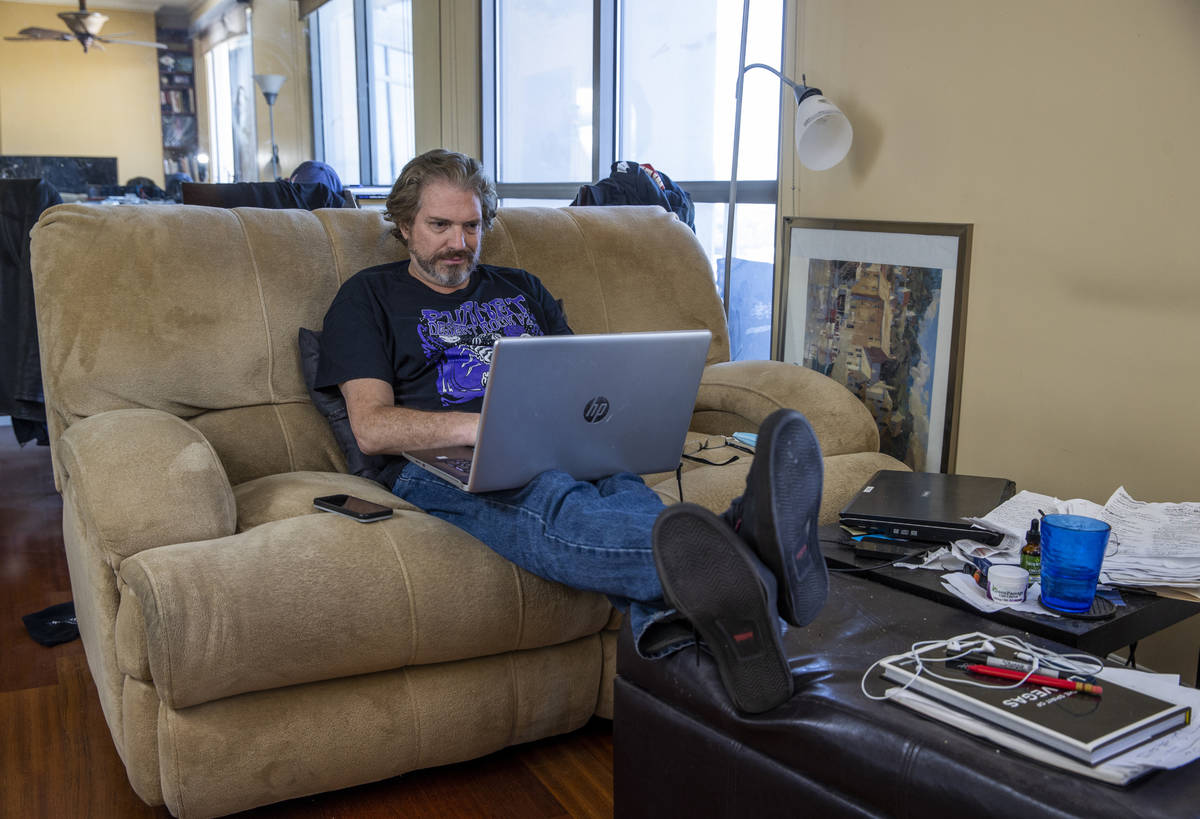

When the pandemic shutdown last spring temporarily froze the blood in Las Vegas’ veins, music promoter John Gist didn’t sweat it, at first — even though he was as much a fixture at local rock shows as amplifier stacks and sheepdog coifs.

“For a hot minute, I embraced it,” recalls Gist, voice as robust as his personality. “I was like, ‘All right, it’s a little timeout. No big deal. I’m an only child. I can handle it.’ And then the realization started kicking in as you watched the news over and over and people are just freaking out.”

Days of isolation turned into weeks. At one point, Gist didn’t leave his condo for a month and a half.

“It really drags you down mentally, someone social like me,” he explains. “It’s been a massive, challenging test to have to deal with it and be alone. I’m a single man, no roommates, so it’s been very lonely. For some of us, we enjoy the social aspects of life, and when you get that cut off, it’s like a drug.

“I try to keep a good attitude,” he continues, “but the fatigue is that there’s still so many limitations and uncertainty, the fatigue of just not having my life back.”

Gist is hardly alone in weathering pandemic fatigue. A year after the coronavirus first put the city on social lockdown, we’re still feeling the impact of the pandemic on our collective mental health.

Though progress is being made in the battle against COVID-19, with vaccinations becoming more available, there’s still a palpable sense of uncertainty hanging like a thick fog obscuring the finish line in the marathon back to normalcy.

Recent decisions by states such as Texas and Mississippi to reopen completely and abandon mask mandates, while other parts of the country take a more measured approach, only add to the confusion and unpredictability.

“Anxiety is rooted in the experience of uncertainty and, in particular, an uncertain threat,” notes Stephen D. Benning, an associate professor in the UNLV Department of Psychology. “Part of why the national uncertainty may be growing now that some states are repealing mask mandates entirely is that they don’t necessarily seem to be doing so based on a consideration of the same facts across states nationwide.

“Because we have a set of state-by-state choices that governments make for their populace,” he continues, “it does not seem as if those governments are always using the same metrics. When people see a lack of consistency in the release of behavioral heath measures that seems divorced from the data, people do become more uncertain.”

It’s all taken a toll on Nevada: A recent report from online insurance platform QuoteWizard ranked the state second in the nation for experiencing the most anxiety or depression during the pandemic, trailing only Louisiana.

Las Vegas has been dealt a particularly savage blow, with the city’s tourism- and entertainment-based economy among the hardest hit in the country.

“It’s definitely been quite a year; the uncertainty of what’s going to happen was the hardest part of it,” says Natalia Badzjo, who co-owns Big B’s Texas BBQ with her husband, Brian Buechner, and serves as the director of customer development at Wynn Las Vegas. “One day everything goes well and we are on the road to reopening, and then two weeks later we get shut down again. Just having no predictability was the biggest factor. This thing was so unknown.”

Severed ties

The headaches eventually landed Stacey Lorene Lockhart in the hospital.

They’d come on at the end of the day, these lightning strikes of pain rolling through her temples like a storm front of jangled nerve endings.

There is a physical dimension to pandemic fatigue, in addition to the mental strain.

Call it feeling Zoomed out.

“I tell you what I’m tired of: Zoom meetings,” sighs Lockhart, executive director of nonprofit HopeLink of Southern Nevada, which provides rental and mortgage assistance, among other services. “I have some days where I swear I’m on Zoom meetings all day long, and by the end of the day, your head hurts and your shoulders hurt.

“For a while, we were doing so many of them that I had headaches so bad that I ended up in the emergency room and had to see a neurologist,” she says. “I think it was from being on the computer, staring so hard, trying to see people and listen. It was overwhelming at one point.”

Running a nonprofit during a pandemic is stressful enough. “We have more money going through HopeLink in one month than they used to have in an entire year,” Lockhart notes, heightened by the dire financial straits many of her clients are in.

“I find myself worrying about everyone else all the time,” says Lockhart, whose husband is at high risk for COVID-19 because of past heart failure. “What are people going to do? What are we going to do to help other people? I have nights (where) I have a hard time sleeping because stuff is constantly going through my head.”

What can make pandemic fatigue especially difficult is that many people have been deprived of some of their normal coping mechanisms, such as in-person encounters with friends and family.

Lockhart, for instance, hasn’t visited her daughter in over a year because she doesn’t want to risk traveling.

“Humans, ultimately, are social creatures,” says David Tatlock, a physical therapist and musician. “When you lose most of the doorways in your life to encounter and enjoy the fellowship of sharing life with other humans, it takes a toll on you.

“I’m very strongly extroverted,” continues Tatlock, who fronts R&B/funk troupe The Soul Juice Band. “So, for me, it’s like a complete life change for a year. I have to operate completely different of my normal personality, how I interact with people.”

This is a challenging adjustment for a self-professed hugger.

“I’m a person who loves human touch, loves human interaction, and I’ve lost a lot of that,” he says. “It’s been difficult on mental health.”

Amplified anxiety

Think of it as being chased by a bear.

That’s what dealing with anxiety and depression can be like.

Sometimes the bear is in the room with us — in the case of a panic attack — its breath hot on our neck.

At other times, it stalks from afar.

We don’t see it — we just know it’s coming for us.

This can result in a prolonged sense of unease, which is exasperated by times like these, with no definitive timetable to put the pandemic behind us.

“That apprehension, that worry, our body’s only designed to deal with that for a certain period of time,” Jay Somers explains while sharing his bear analogy. “Ten thousand years ago, we were running away from a bear, it lasted 10, 15 minutes. We either got away or the bear got us. It didn’t go on for months.

“The adrenal gland in our body produces stress hormones,” adds Somers, a physician assistant working at Nevada Family Psychiatry. “We’re designed to run away or to fight danger, but that danger is not meant to last for days or weeks or months or years. When it does, we get into this fatigue state. I think that’s what’s gripping people the most these days. They’re not acutely impaired, but they’re chronically impaired to the point where it’s really starting to affect their lives.”

Especially concerning is that these issues could have lingering effects.

“People are having more mental health symptoms than they normally would, and that increase seems to persist over time,” UNLV’s Benning says. “One of the things that was really striking about why some of these symptom changes occurred is that they occurred when people’s physical activity decreased and their screen time increased.

What’s disheartening “is that when there was an intervention done to increase people’s physical activity, that didn’t lead to a rebound of their mood or a decrease in their depression symptoms or anxiety symptoms. “What it suggests is that it’s not necessarily the lack of physical activity itself that has contributed to people’s increased symptoms, but rather the lack of social connection,” Benning says.

“Coronavirus has caused all sorts of losses in our lives,” Somers says. “Not being able to connect with family and friends, and losing things like birthdays and anniversaries and holidays, as with many things in our lives, we don’t realize how important these events are until we can’t do them anymore.

“That really has this kind of lingering effect,” he continues. “It’s kind of like walking with an anchor behind you. You can do it for a short period of time, but suddenly you’re like, ‘Oh, my god, this is really tough.’ ”

Finding a way to cope

It’s 10 a.m. and she’s still in her pajamas.

This is a rare moment for HopeLink’s Lockhart, who is normally up and at it by 4:30 a.m.

This past Monday, though, was different.

“I got up this morning and I was just like, ‘I’m tired. All of this, all of the time,’ ” she says. “I finally went, ‘You know what? I’m taking a day just to chill.’ ”

Hitting pause on life is one way of attempting to manage pandemic fatigue.

Tatlock has coped, in part, by using his medical research background to parse various COVID-19 studies available on science search engines such as PubMed and then sharing the data on his Facebook page.

“I was just trying to give out good information. That might have been my way to press through it,” he says. “I started becoming this guy who was trying to peddle hope.”

Of course, there is no universal panacea for easing the mental strain of an ongoing pandemic.

“The reality is that there’s no magic pill, there’s no mantra, there’s no perfect therapy that suddenly makes this all reasonable,” Somers says.

For restaurant owner Badzjo, it’s been about maintaining a glass-half-full perspective — even if the glass occasionally has seemed like it was full of rancid milk.

“For a while, when we went back to the harsher restrictions, I was ready to throw my hands up, like, ‘Let’s just shut down for a few weeks and be done with it,’ ” she acknowledges. “But I’m glad I didn’t. It definitely took some internal fights to decide, ‘OK, let’s just keep going.’ A lot of people were in the same boat, just too tired of fighting, but I feel optimistic now, just seeing people be more comfortable and seeing things coming back slowly but surely.”

Music promoter Gist also says his perspective has brightened of late.

One key for him: watching less news coverage of COVID-19, which he contracted last year.

He keeps his mind off things by taking long drives, cranking his favorite bands until those bands can return to the stage.

“I try not to over-stress,” he says. “This COVID taxes our brain, man.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter and @jbracelin76 on Instagram.