Mesquite hospital’s closure of obstetrics unit opens generation divide

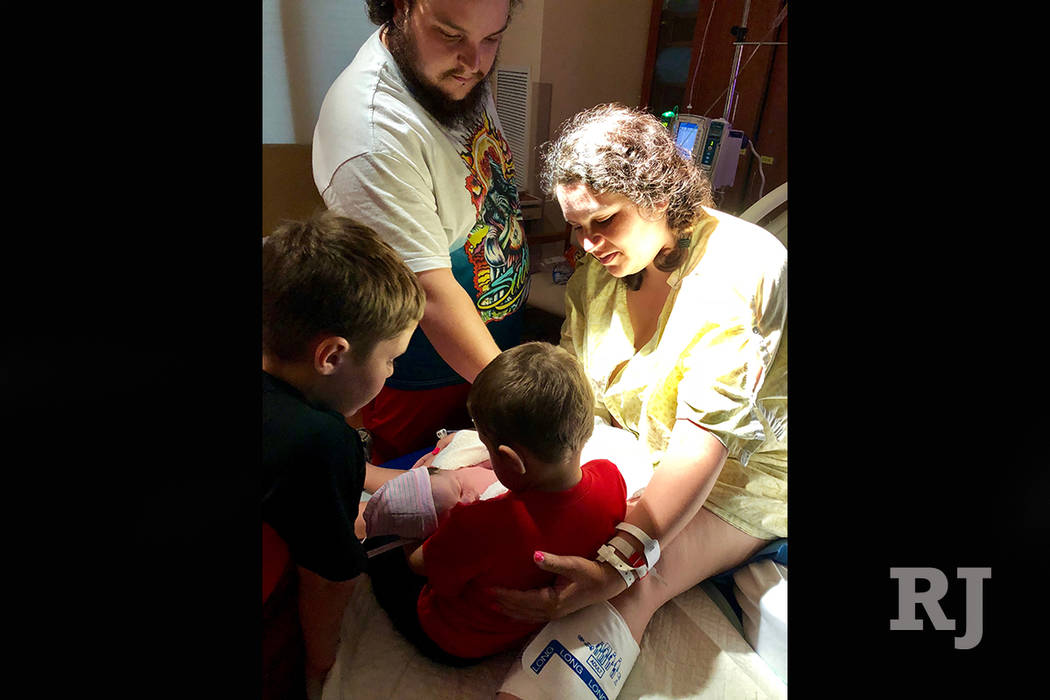

MESQUITE — Amanda Cook dreamed of being a mom of four until Mesa View Regional Hospital closed its labor and delivery unit last week.

Now, she says, having another baby could mean the difference between being a living mother of three or dying during childbirth and leaving four children motherless.

“I don’t want to have one more baby if there’s not a safe way for the baby to be delivered,” said Cook, 28, a Mesquite resident since 1996 who has a blood clotting disorder that makes childbirth risky.

The hospital’s labor unit and nursery closed Oct. 1, despite a 2002 development agreement under which the city provided the land for the hospital for $1 in exchange for it providing a list of services, obstetrics included.

Since the closure, moms-to-be must now travel to deliver their babies in a hospital, either to St. George, Utah, about 40 miles northeast, or to a hospital in Las Vegas, 82 miles southwest.

Cook is one of several Mesquite residents who voiced concerns at a Sept. 11 City Council meeting, saying that the closure of the town’s labor and delivery unit would drive out young families and keep new ones from moving to a city where more than half of the residents are over 50, according to census data.

Divide between young and old

Theresa Woolridge-Ofori, a Mesquite dentist and wife to one of two obstetrician-gynecologists in the fast-growing town of 18,500, said that the closure had opened a divide between the town’s young and old.

“Young people in this community are sick of being disenfranchised when it comes to issues that concern us,” she told council members.

Though hospital officials discussed closing the unit in 2012, the city didn’t agree to a contract amendment authorizing the change, and the unit stayed open. But the disagreement boiled over in late August, when Mesa View’s new CEO Ned Hill announced the closure, saying demand is “simply not there.”

According to the hospital, deliveries at Mesa View have decreased by 74 percent in the last decade, dwindling to 63 in 2017.

“Discontinuing elective deliveries will allow our hospital to continue building up the services most needed in our community,” Hill said, adding that the hospital hired five new practitioners in other specialties with the money saved from the closure.

The city is trying to force the hospital to reopen the unit.

In a complaint filed in District Court last month, it argued the hospital violated the 2002 agreement by closing the unit four years before the 20-year contract ended. The hospital argued that the contract was not enforceable because it doesn’t reference a state law that governs development agreements.

District Court Judge Richard Scotti denied the city’s motion for a temporary restraining order and a hearing for a preliminary injunction. Mesquite City Attorney Bob Sweetin said the city plans to file a separate motion for a preliminary injunction while the court decides whether Mesa View is bound by its existing contract.

Residents argued at the Sept. 11 meeting there might be a few reasons for the decrease. Mindy Hughes, 36, said she already planned to deliver at Dixie Regional Medical Center in St. George because their bills from the nonprofit hospital would be less than at Mesa View. Shae Stricker, 27, was planning to deliver her third child at Mesa View, but didn’t mind heading to St. George — her previous two were born at Dixie Regional Medical Center.

If a woman is in labor and can’t travel to St. George or Las Vegas, she can still deliver at Mesa View’s emergency department. That’s where paramedics have been instructed to take patients, said fire Capt. Spencer Lewis. “It’s far better for the mother and baby to deliver in a clean, sterile environment than moving down the road,” he said.

He acknowledged that crews aren’t trained to check how much a woman is dilated.

“The only thing we check for is if the head is coming out,” he said, adding that while he doesn’t expect a significant increase in call volume, Mesquite’s first responders are on edge with the additional responsibility.

‘A mom is going to die’

Dr. Joseph Adashek, a Las Vegas OB-GYN who specializes in high-risk pregnancies, said he worries that lack of access to specialized care could result in more complications for women with otherwise healthy pregnancies. Moreover, delivering in an ER increases risk for mothers and their newborns, he said, because ERs generally don’t have pain management tools, like epidural shots, or the skills and equipment to resuscitate a baby.

“The emergency room is a bad place to have a baby; it’s just not set up for it,” Adashek said. “Even for us (obstetricians), when we go to deliver a baby in an emergency room, it’s much more difficult, and they don’t have the supplies. A mom is going to die, and until that happens enough no one is going to (have the) political will to change it. It’s inevitable if you have to go that far for health care.”