Headaches, dizziness vanish after innovative aneurysm surgery

Two years ago the symptoms first hit. Headaches pounded her to tears. Dizziness dropped her to her knees.

They would come and go, but happened enough to send the then-77-year-old Mabelle "Mickey" Wiedeman, who generally chalked up her aches and pains to old age, to the doctor.

Medical tests showed a bulging, weakened area in the wall of her brain — an aneurysm, what looked on imaging scans much like a berry hanging on a stem. If it burst, there would be bleeding into the brain, which is often fatal.

Referred to a neurosurgeon, Wiedeman wept as he told her that at her age removing part of her skull to sort through brain tissue to clip the ballooning aneurysm was just too risky — she probably would die on the operating table.

"He said it was inoperable and gave me some dizzy pills," Wiedeman, now 79, recalled recently as she sat in the living room of her east side condo with her disabled husband. "I didn’t want to die because I didn’t know who would take care of Bill."

For a while the medication lessened her symptoms. But around the first of this year the headaches again began to hammer and the dizziness caused her to fall in her house, then in the driveway.

Not expecting much more than stronger pills, she drove her old Lincoln to a general practitioner. This time, instead of a surgeon, she was referred to an interventional radiologist, Dr. Raj Agrawal.

To her surprise, he said he could treat the growing aneurysm — one he felt sure would burst within a year if left untreated — with "coiling," where a catheter is used to thread, then deploy platinum coils inside the aneurysm, blocking blood flow into the bulge to prevent it from exploding.

In March, he performed the four-hour procedure at Valley Hospital. Today, the aneurysm is no more. Ditto for Wiedeman’s dizziness and headaches.

Margo Sayre, an administrator at Valley, points to Wiedeman’s experience as a reason for people to become aware of all their treatment options.

"Ask questions," Sayre said. "In modern medicine there is often more than one way to go."

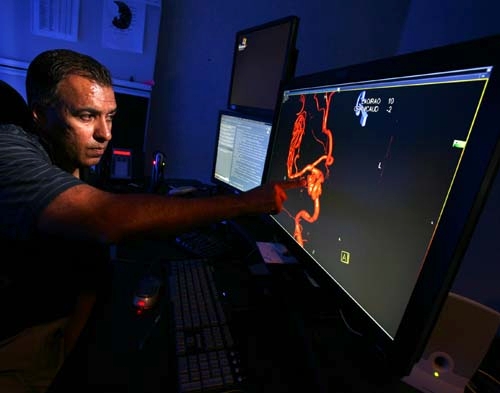

The other day Agrawal sat in a darkened imaging room in an office complex near Eastern Avenue and East Flamingo Road, pointed at the screen and explained the procedure he performed on Wiedeman.

There, in bright orange on a black screen, was what he saw before the procedure: A bulge in an artery on the right side of her brain. One centimeter in size, referred to by Agrawal as "huge," the aneurysm had grown four millimeters in less than two years.

"If I didn’t have this 3-D imaging, I wouldn’t have been able to do the procedure, or if I did, it would have been more risky," he said. "But this really lets me see what I’m getting into in the brain."

The 43-year-old Agrawal said people still are often surprised when they are sent to a radiologist for treatment of a serious condition.

"There are people who hear the word radiologist and think of someone who reads X-rays," the graduate of the Northwestern University School of Medicine said.

Interventional radiology has been around for more than 30 years and is responsible for much of the medical innovation, including the development of minimally invasive procedures that are commonplace today. In interventional radiology, images are used to direct procedures, which are usually done with needles and narrow tubes called catheters. Abscess fluids can be drained this way, infected bile removed, blood clots dissolved.

The interventional procedure most people are familiar with is the balloon angioplasty cardiologists use for treatment of heart disease. It involves opening narrow or blocked blood vessels with a balloon, and may include placement of stents to keep the vessels open.

The coiling technique used by Agrawal on Wiedeman largely was developed in the mid-’90s. The goal is to isolate an aneurysm from the normal circulation without blocking off any small arteries nearby or narrowing the main blood vessel.

On the day of the procedure, Agrawal did what he always does when he goes to the operating room. He skipped the coffee he loves. Even a small tremor in his hands could prove disastrous.

As strange as it may seem for a procedure involving the brain, Agrawal entered the bloodstream with a flexible catheter through the large femoral artery in the groin area.

"That’s the safest way, a large artery that most people have open," he said.

While viewing an X-ray monitor called a fluoroscope, Agrawal advanced the catheter to an artery in the neck that leads to the brain, carefully steering the tube through blood vessels — a special dye injected into the bloodstream makes the blood vessels appear on the monitor, creating a kind of road map.

At one point during the procedure, Agrawal thought he would have to stop. Wiedeman’s arteries were what he termed "loopy" from high blood pressure.

"When they’re not straight, it’s kind of like roadway that get cracks and it’s much more difficult to get the catheter through," he said.

Aware that her only chance to keep an aneurysm from bursting lay in his hands, Agrawal pressed on, finally negotiating his way to the bulge.

A very thin platinum wire was inserted through the catheter and into the aneurysm. The wire coiled up as it entered the area and then was detached. Multiple coils were packed inside the aneurysm to block normal blood flow.

In the days ahead, a clot would form inside the aneurysm, effectively removing the risk of aneurysm rupture. The coils are now part of her.

After one night in the hospital, Wiedeman went home.

She loves the fact that her case is pointed to by the Valley Health System as an example of what minimally invasive surgery can do.

"More people need to know about this kind of thing," she said. "I don’t understand how it was done but I do understand this: It kept me alive."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.