Are nutritional labels coming on alcoholic drinks?

WASHINGTON — Alcoholic beverages soon could have nutritional labels like those on food packaging, but only if the producers want to put them there.

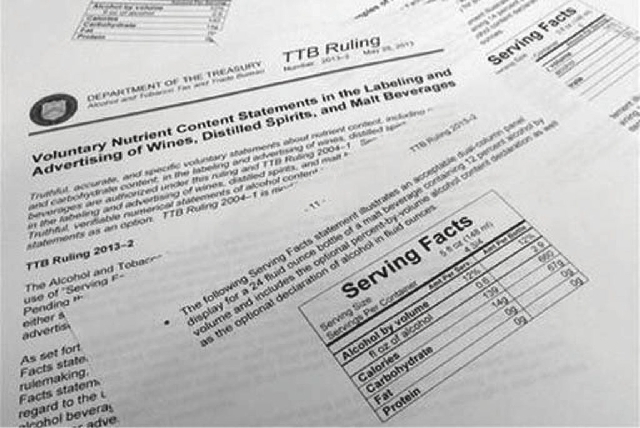

The Treasury Department, which regulates alcohol, said this past week that beer, wine and spirits companies can use labels that include serving size, servings per container, calories, carbohydrates, protein and fat per serving. Such package labels have never before been approved.

The labels are voluntary, so it will be up to beverage companies to decide whether to use them on their products.

The decision is a temporary, first step while the Alcohol and Tobacco Trade and Tax Bureau, or TTB, continues to consider final rules on alcohol labels. Rules proposed in 2007 would have made labels mandatory, but the agency never made the rules final.

The labeling regulation, issued May 28, comes after a decade of lobbying by hard liquor companies and consumer groups, with clearly different goals.

The liquor companies want to advertise low calories and low carbohydrates in their products. Consumer groups want alcoholic drinks to have the same transparency as packaged foods, which are required to be labeled.

“This is actually bringing alcoholic beverages into the modern era,” says Guy Smith, an executive vice president at Diageo, the world’s largest distiller and maker of such well-known brands as Johnnie Walker, Smirnoff, Jose Cuervo and Tanqueray.

Diageo asked the bureau in 2003 to allow the company to add that information to its products as low-carbohydrate diets were gaining in popularity.

Almost 10 years later, Smith said he expects Diageo gradually to put the new labels on all of its products, which include a small number of beer and wine companies.

“It’s something consumers have come to expect,” Smith said. “In time, it’s going to be, why isn’t it there?”

Not all alcohol companies are expected to use labels. Among those that may take a pass are beer companies, which don’t want consumers counting calories, and winemakers, which don’t want to ruin the sleek look of their bottles.

The Wine Institute, which represents more than a thousand California wineries, said in a statement that it supports the ruling but “experience suggests that such information is not a key factor in consumer purchase decisions about wine.”

Spokeswoman Gladys Horiuchi said the group knows of no wine companies that plan to use the new labels.

The beer industry praised the agency for acknowledging that labels should take into account variations in the concentration of alcohol content in different products.

The industry has opposed the idea of defining serving size by fluid ounces of pure alcohol – or as 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof liquor – on the grounds that you may get more than 1.5 ounces of liquor in a cocktail depending on what else is in the drink and the accuracy of the bartender.

The ruling would allow the labels to declare alcohol content as a percentage of alcohol by volume, the approach favored by the beer industry.

“We applaud the TTB’s conclusion that rules be based on how drinks are actually served and consumed,” said Joe McClain, president of the Beer Institute.

McClain said the beer industry is pleased that the ruling provides “substantial flexibility” in terms of the format and placement of the disclosure on packaging.

It is unclear whether beer companies will actually use the labels, however.

Consumer advocates criticized the regulation.

“It doesn’t reflect any concern about public health,” said Michael Jacobson, director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest. He said the rules are too close to what the alcohol companies had sought.

Consumer advocates have said that listing alcohol content should be mandatory so consumers know how much they are drinking. Jacobson and others also support having calorie counts on labels, but they said the labels should not include nutrients that make the alcohol seem more like a food.

“Including fat and carbohydrates on a label could imply that an alcoholic beverage is positively healthful, especially when the drink’s alcohol content isn’t prominently labeled,” Jacobson said.

Current labeling law is complicated.

Wines containing 14 percent or more alcohol by volume must list alcohol content. Wines that are 7 percent to 14 percent alcohol by volume may list alcohol content or put “light” or “table” wine on the label. “Light” beers must list calorie and carbohydrate content only. Liquor must list alcohol content by volume and may also list proof, a measure of alcoholic strength.

Wine, beer and liquor manufacturers don’t have to list ingredients but must list substances people might be sensitive to, such as sulfites, certain food colorings and aspartame.

Tom Hogue of the TTB said the aim of the ruling is to make sure alcohol labeling is more consistent. “The idea here is we are trying to make it easy for the industry to communicate this with consumers if they want to do so, and if their consumers want them to do it,” he said.