Can pop-up sites bring vaccine equity to hard-hit neighborhoods?

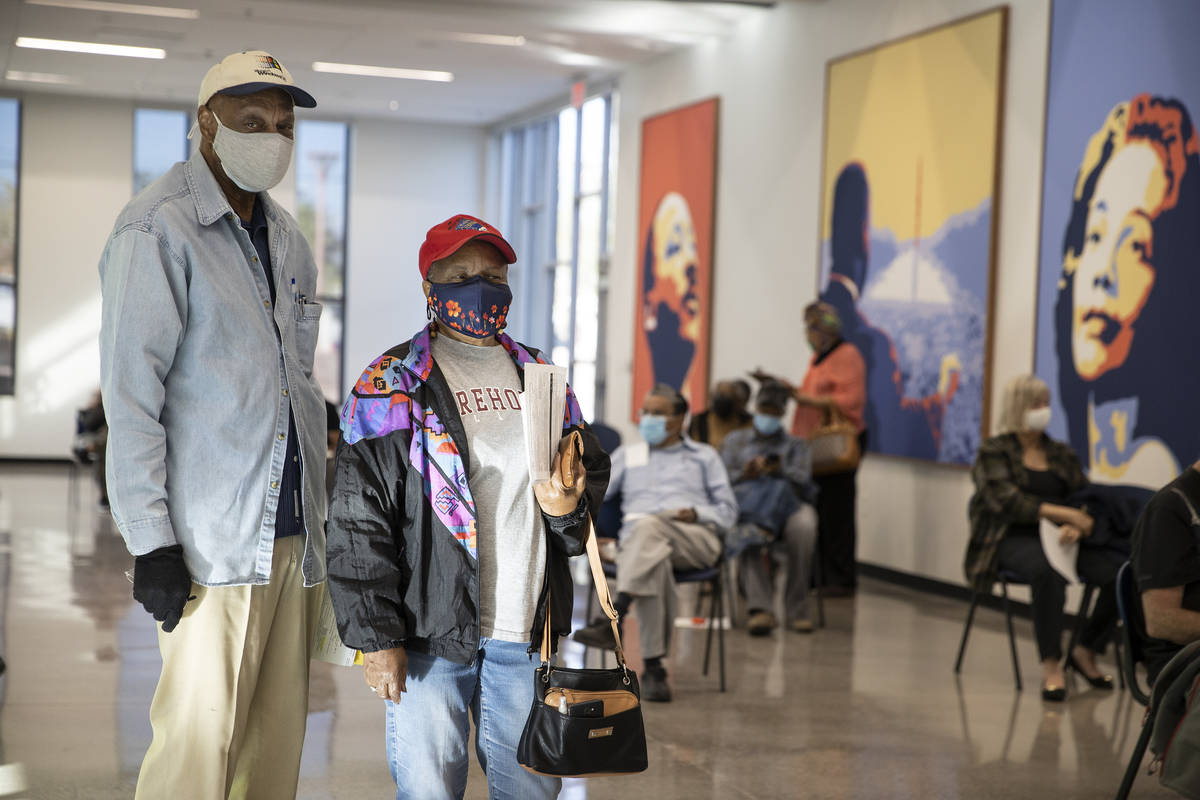

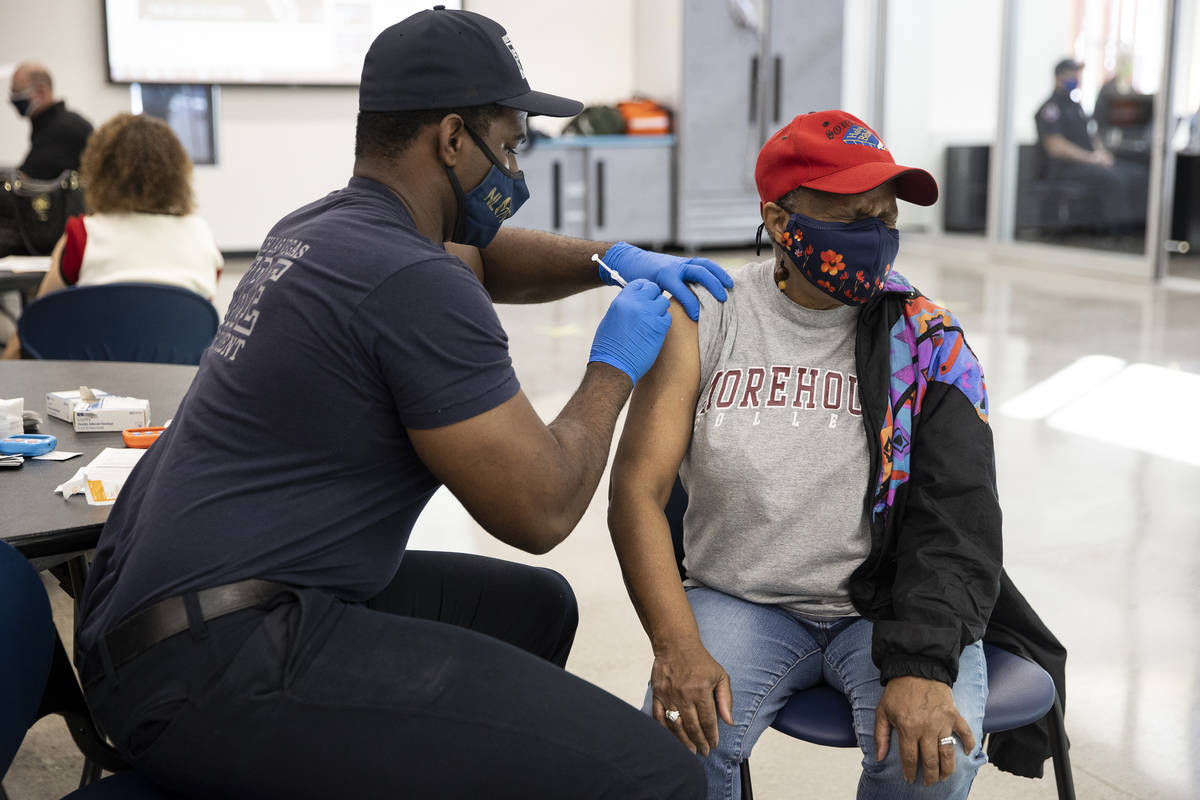

Henrietta Peterson felt relief as she pulled her windbreaker over the Band-Aid on her right shoulder.

It was Wednesday morning in North Las Vegas, and the 72-year-old city resident had just received her first dose of the highly sought-after COVID-19 vaccine. She and her husband, Ernest Conner, had spent weeks searching for an appointment before receiving an invitation to a city-run clinic at the Martin Luther King Jr. Senior Center.

“There was nowhere for us to register,” Peterson said. “They should have came here first, because this is the area that’s been affected the most.”

The two-day clinic was among the region’s first preferential vaccination events, offering hundreds of shots to the senior center’s mostly Black and Latino membership roster before inviting the general public. Officials say it will be far from the last.

Recent data shows a relatively small number of vaccines are going to residents of local Black and Latino neighborhoods where COVID-19 cases have proliferated. Across Southern Nevada, the two minority groups have been immunized at disproportionately low rates compared with their white and Asian counterparts.

Gov. Steve Sisolak last week said Southern Nevada faced an “equity crisis” and called for local leaders to take action as part of an Equity and Fairness Initiative. Sisolak’s office also created an equity task force to address issues statewide that should begin to meet this month.

“I know that the counties are aware of that. I know that the local leaders are aware of that. I know that the health districts are aware of that,” Sisolak said during a news conference Thursday. “And it’s incumbent upon them to take that information and hopefully move forward with it.”

The disparities have raised alarm among officials, who point to national data showing minority groups are more likely than white people to be hospitalized or killed by COVID-19. Local data shows Asian and Pacific Islander residents are most often dying here, followed by white residents.

Dr. Fermin Leguen, chief health officer of the Southern Nevada Health District, says he disagrees with the governor’s grim assessment. Administering vaccines to two prioritization lanes — essential workers and the general public — have so far skewed data on recipients, he said.

However, the health district is already modifying its vaccination strategy to deliver more shots to diverse communities.

“We cannot just sit here and wait for inequalities to be addressed by themselves,” Leguen said.

That includes opening more clinics that give preferential access to residents of hard-hit communities including North Las Vegas, east Las Vegas and Las Vegas’s Historic Westside. Community organizations and leaders would be tasked with registering people for appointments.

Leguen said he is considering setting aside as much as one-fifth of the more than 20,000 doses the health district receives each week for the initiative.

State and local officials have created hotlines to help people without computer or Internet access to register for appointments. Public and private organizations are helping transport people who don’t drive to appointments.

But improving access to vaccination opportunities isn’t enough, officials say. Many Black and Latino residents still have not decided to be immunized.

As of late January, both groups were more likely to adopt a “wait and see” vaccination strategy than were white people, according to a nationwide Kaiser Family Foundation survey. Most said they did not have enough information about the vaccine’s effectiveness and side effects.

The state has partnered with the Nevada Minority Health &Equity Coalition to develop a vaccine outreach campaign for minority communities.

“If we haven’t communicated well enough about the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, or kind of counteract the disinformation part of this, then we’re really not doing anything,” coalition vice chair and UNLV public health professor Erika Marquez said.

Leaders: Trust is key

In Southern Nevada, Black and Latino community leaders have become crucial partners in spreading information about the vaccine.

This week they and local doctors held an hourlong “myths vs. facts” vaccine webinar for the public and answered questions about the contents of the vaccine and how it works.

Black residents who are wary of the vaccine often reference the decades-long, unethical “Tuskegee experiment,” NAACP Las Vegas branch president Roxann McCoy said. From the 1930s to early ’70s, federal researchers lied to hundreds of Black men in Alabama about giving them health care, and instead studied the effect of untreated syphilis on them.

“We don’t trust everything that white people say, and there’s a history that says why we cannot,” she said.

Jacqueline Perkins-Denmark, a retired nurse who is Black, said her family members bring up the Tuskegee experiment when she asks them about taking the COVID-19 vaccine.

“They think they’re trying to put something in us,” said Perkins-Denmark, who received her first dose Wednesday. “I try to talk to them, but people are so defiant. I have to let them do what they’re going to do.”

Latinos have distrust, too

Many Latinos also distrust the vaccination process, community leaders say.

They fear their personal information could be given to immigration authorities, leading officials to discuss opening a clinic at the Mexican Consulate in downtown Las Vegas.

“The language, the culture and seeing someone familiar creates a good environment for them to ask about their health, employment issues, legal issues and getting the vaccine,” consul Julian Escutia Rodriguez said.

To connect with more Latinos, officials are reaching out on Spanish-language television and radio stations. The “Esta en Tus Manos” COVID-19 outreach campaign now includes vaccine information and encourages young Latinos in multigenerational households to help their elders register for appointments.

“It has been a very natural next step,” Rodriguez said of expanding the campaign. “We already have the partnerships, the network, the media outlets and social media messaging.”

Across different racial and ethnic groups, McCoy said, community leaders are helping build trust by simply getting the vaccine and making themselves available to answer questions about how they feel.

Religious leaders have been an especially powerful ally. The dozen churches that form the Faith Organizing Alliance are distributing information to thousands of congregants and helping them find appointments.

“We’re saying when you make the decision, make sure it’s an educated decision and not based on rumors,” the Rev. Leonard Jackson said. “The majority of people in our community that I’ve spoken to feel they cannot trust the government. … They trust their church.”

Plan in North Las Vegas

Southern Nevada’s most diverse city has launched its own equity initiative.

North Las Vegas officials are targeting the 89030 ZIP code, a working-class Latino neighborhood that has seen one of the highest infection rates in Southern Nevada. About 1 of every 7 residents has contracted COVID-19, and more than 120 people have died.

In addition to the vaccination clinic held at the Martin Luther King Jr. Senior Center, city paramedics have vaccinated hundreds of residents at two senior apartment complexes in the ZIP code this month.

Another facet of the strategy involves meeting residents where they are. The city is registering people for vaccination at churches and supermarkets.

The focused pop-up sites will complement the city’s permanent vaccination site at Canyon Springs High School, which is open to the public at large.

The permanent site serves city residents at large, but registration data shows thousands of people living outside North Las Vegas have registered there as well.

“We were getting people from all over the valley, and we wanted to start targeting our communities in North Las Vegas,” City Manager Ryann Juden said. “Anytime you’re trying to create equity, you have to be intentional.”

Contact Michael Scott Davidson at sdavidson@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3861. Follow @davidsonlvrj on Twitter.