DESERT DESIGNS

Goodbye, tile roofs, beige stucco and ornate details. Hello to streamlined shapes, local materials and homes topped with solar panels that seem to blend seamlessly into the land around them. Desert contemporary architecture is on the rise in Las Vegas, and the architects behind a new luxury-home community aim to give the trend some staying power.

From a stunning sales office-slash-educational center perched on a Henderson ridge, the Ascaya development is embarking on one of the most stringent design review processes in the valley. The goal: to ensure that its custom residences reflect a sensitivity to Las Vegas’ sun, wind and views, and to inspire other developers to do the same.

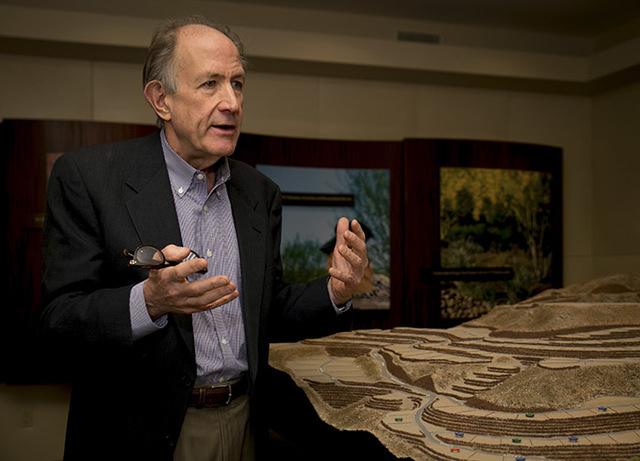

“When you come to Las Vegas, it’s an incredibly beautiful, stark desert, so you’re brought down to the basic elements of nature,” said John Sather, a principal at Scottsdale, Ariz.-based Swaback Partners and lead architect on Ascaya, where construction will begin in the next few months.

“There is a real desire on the part of Ascaya’s developers to see that this becomes one of the finest collections of desert architecture of its time,” Sather said.

As much a philosophy as a style, desert contemporary design blurs the distinction between the indoors and outdoors with features such as glass walls and outdoor living rooms. Architects use elements such as wide overhangs and deep-set windows to provide shade and a sense of shelter.

Lines are clean and simple, and sustainability and energy efficiency are paramount.

The movement harks back to famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright and his disciples who built desert modern homes in Arizona and Palm Springs, Calif., beginning at midcentury.

“A lot of them had shed the preconceived notions of what architecture was and all these architectural languages that had developed over centuries,” said C.J. Hoogland, whose firm designs contemporary homes in Las Vegas. “This was postwar and they were capitalizing on new manufacturing processes, materials and ways of thinking about communities. It was the atomic age and we were constantly looking forward.”

For today’s local design pioneers, finding that cutting edge might mean building a gray-water system to recycle water from sinks and washing machines, or incorporating sensors that measure a home’s energy use.

At a Blue Heron Homes model in Seven Hills, sliding glass doors disappear at the push of a button, suddenly transforming an indoor shower into an outdoor one, an entryway into a breezy patio that gives onto a reflecting pool. The company’s “Vegas modern” style combines natural and recycled materials with the kind of Sin City bling that custom homebuyers here expect—from a dramatic sunken living room flanked by pools to a lounge that converts to a home theater seemingly by magic.

When the company began in 2004, many were skeptical it could succeed in a landscape dominated by Tuscan McMansions, owner Tyler Jones said.

“They said, ‘This isn’t New York or San Francisco, you’re going to fail. What are you doing?’

“The exact opposite was true. There wasn’t anything in this style but it wasn’t because people weren’t interested in it; they just hadn’t seen it before.”

The development of the Ridges in Summerlin over the past 15 years has given builders room to experiment with contemporary designs, said architect Arthur Elliott, who has consulted on design review boards in the valley for two decades. Developer Howard Hughes Corp. encouraged desert-appropriate houses, setting height limits and asking builders to use warm colors and horizontal lines.

At first, the homes looked more traditional Elliott said. “All the contractors were hesitant to do flat roofs. Now the technology has evolved, and the shapes tend to be more flat. We’re also seeing more smooth stone, polished travertine, and a real acceptance of the pocket glass that opens to create a more indoor-outdoor experience.”

Las Vegas’ commercial architecture, too, has evolved, with the glittering CityCenter and Frank Gehry’s sinuous Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health providing homebuilders with examples of more avant-garde structures. Even TV and the Internet are likely influencing local buyers who want to replicate the look they see on period dramas such as “Mad Men” or websites such as Houzz, where midcentury modern is all the rage.

Ascaya’s team wants to help educate and inspire buyers and architects interested in undertaking a desert contemporary project, but not be sure where to begin. Designed by Sather, the community’s sales center commands sweeping city views and includes a two-story atrium overlooking a meticulously curated zero-scape garden.

Details of the courtyard oasis demonstrate the development’s emphasis on sophistication and sustainability. Paving and gravel come from the excavation of terraces where Ascaya’s 300-plus homes will eventually sit. Sun dapples the top of a rough stone wall, topped with fluted block that evokes the ribs of a cactus. Palo verde and ironwood trees help shade the building’s lower windows, while louvers provide shadow on the second story. (An upcoming clubhouse will use similar architectural elements on a larger scale.)

“There’s no grass here because we don’t want to promote it at all,” Sather said.

Architects will be required to conduct sun and shading studies on their sites, something not typically mandated by design review boards. Inside the sales center, a lending library contains books on great residential architecture. Sather hopes architects will use the room as a place to sketch and dream.

“There may be architects who aren’t accomplished desert architects but they are accomplished in their own right,” he said. “Part of this is helping them understand how to work with the sun, utilize drought-tolerant plants and build green, sustainable residences. I look at myself as kind of a conductor of a symphony.”

While Ascaya’s available lots range from the mid-$600,000s to just under $3 million, not including construction costs, desert contemporary design isn’t just for the 1 percent. At the Springs Preserve, visitors flock to DesertSol, a solar-powered, 750-square-foot house created by students at UNLV that took second place in the U.S. Energy Department’s Solar Decathlon in 2013.

Like other desert contemporary structures, the petite home defies stereotypes of modern architecture as cold and forbidding. Students created a cozy atmosphere using reclaimed wood, rich textures and acoustic absorbers to reduce echoes. Many of the home’s energy-saving features can be replicated on a budget, said Eric Weber, director of UNLV’s David G. Howryla Design Build Studio.

“One of the key things to do in this environment is make sure you know where to place your windows,” Weber said. “Putting large windows on the west side of a building without shade is a really bad thing. That’s doesn’t cost money; it’s just smart design.”

Developers are also experimenting with the style at a somewhat more affordable price point in at least two new communities—Sterling Ridge, a William Lyon semi-custom home tract within The Ridges and The Cliffs, a Howard Hughes village set to take shape at Summerlin’s southern edge.

Could Las Vegas, a city that’s made its fortune on mimicry, finally find a signature style in desert contemporary? Perhaps. At the very least, the recession and its aftermath have pushed homebuilders to become more creative, Weber said.

“The developers at Ascaya are trying to differentiate themselves, saying we’re not doing business as usual, we’re trying to create a new market,” he said. “That’s actually a brilliant strategy.”

Rising energy costs could also increase Las Vegans’ interest in desert-sensitive homes, Hoogland said.

“I think that as energy prices continue to go up, consumers will be looking more and more for architecture that actually can give back, that can produce energy instead of be a liability,” he said.

“In Las Vegas, we’ve erased the past by imploding our buildings but we haven’t really gotten beyond what’s trendy right now. And we need to take that step and look forward to what architecture can be for the next generation. What is the legacy that we’re going to leave?”