Music and Image

The robot on the phone isn’t really a robot, though Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo may occasionally argue otherwise.

He’s a man without a face, a stack of dog-eared back issues of "Popular Mechanics" come to life.

His visage is largely unknown to the public at large, blurred in photographs, enshrouded in ominous-looking black sacks in interviews, encased in a hi-tech, LED helmet onstage.

As one-half of Parisian electronica duo Daft Punk, de Homem-Christo wraps himself in futuristic-looking headgear and leather jumpsuits, looking like something that sprang from Isaac Asimov’s mind’s eye.

"It’s really impossible for us to separate the music and the image," he says. "It’s funny, we appear as robots from another world, but what we do, what the robots create, is really human after all."

And that’s the appeal of Daft Punk, as counterintuitive as it may seem: Though they dress as otherworldly automatons, they’ve helped humanize electronica, oddly enough, by adding a warmth and an organic edge to a style of music that can veer toward the steely and mechanical at times.

The band’s 1997 debut, "Homework," is a sweaty, animated caricature of electronic funk that enlivened the genre with bright, dive-bombing beats, ecstatic synth lines and a cheeky playfulness from two dudes who seem as if they crawled out of a comic book.

"It’s true that we come from the electronic scene in the ’90s, but maybe just two years before that we were not listening to electronic music," de Homem-Christo says. "We like music in general, and maybe we’re more close to the rock energy or the rock aesthetic.

"We like more of the package of rock music than just electronic or techno music, which, in general, is really more cold," he continues. " ‘Homework,’ if you look at the record sleeve and all the imagery, it’s this small world that we’ve tried to create since the beginning of Daft Punk. We’ve always been more into the rock ‘n’ roll imagery."

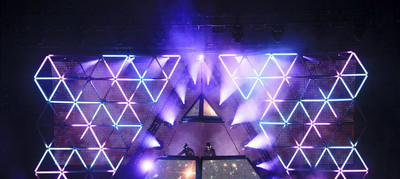

Live, de Homem-Christo and bandmate Thomas Bangalter do away with the traditional DJ presentation in favor of an explosion of color and sound that’s akin to entering a giant, phosphorescent subwoofer.

Currently, they perform amidst a towering pyramid of flashing lights, which, combined with the duo’s seismic rhythms and thick clouds of dry ice, creates a near-hallucinogenic effect, like a disco version of "Close Encounters of the Third Kind."

It’s a blinding, enveloping spectacle on par with any big budget arena rock production going these days.

"The show we bring can maybe have an appeal for rock fans as well as electronic music fans," de Homem-Christo says. "For us, we’ve always been making music, and not especially electronic music — hip-hop is made with exactly the same instruments we use. On our last album, ‘Human After All,’ we did everything with rock guitar, regular electric guitar. We just make music, and that’s it."

That music has begun to impact the American mainstream more and more of late, albeit in sometimes unlikely contexts.

They’ve appeared in Gap ads, fostered dance floor disciples like Justice and Digitalism and watched as big name rappers Busta Rhymes and Kanye West notched hits in the past year built around Daft Punk samples.

Daft Punk’s catalog is so diffuse, it’s unsurprising that their audience would be, too: Their songs are built around the kind of big, buoyant hooks that resonate with pop fans, their beats are fierce enough to court the hip-hop crowd and it’s delivered with enough power, volume and torque to move even the most stiff-limbed headbanger.

Much like images of their unadorned faces, the notion of genre distinctions are something that these two never have had much use for.

Consider it dated technology.

"When we began Daft Punk, by the albums we made, by the interviews we did and by every opportunity we had we tried to break all the boundaries between musical genres," de Homem-Christo says.

"It’s good for people not to have a narrow mind," he adds. "Good music is good music."