Movies help fuel ‘Myth of the Mob’

The Mob Museum without mob movies? Fuhgeddaboutit.

Never fear; they didn’t.

Instead, the National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement — better known as the Mob Museum, which opens next month in downtown Las Vegas on the 83rd anniversary of Chicago’s notorious St. Valentine’s Day Massacre — went directly to an expert source.

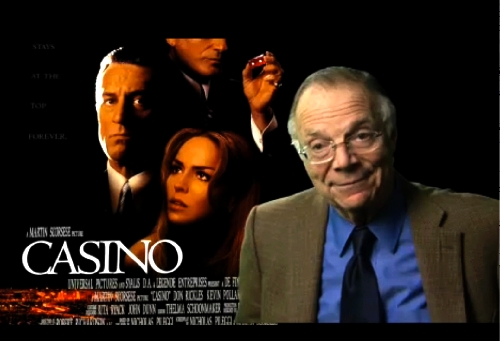

Author and screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi, whose credits include such gangster classics as 1990’s “Goodfellas” and 1995’s made-in-Vegas “Casino,” hosts a documentary short that explores how movies — including his collaborations with director Martin Scorsese — have contributed to, and influenced, “The Myth of the Mob.”

Audiences “like movies about the mob because they’re life writ large,” Pileggi says in the documentary. “You don’t really want to sit around and watch a movie about dentists — you know, with wonderful wives and nice kids who all go to school. I mean, there’s not a movie there. Drama has to be bigger than life.”

And “Casino” definitely qualifies on that score, Pileggi contends.

The culmination of a Scorsese-directed mob trilogy that begins with the low-level criminals of New York’s “Mean Streets” (1973) and continues with “Goodfellas’ ” midlevel hoods, “Casino” qualifies as the most “complicated” of the three pictures, in Pileggi’s view.

Unlike “Goodfellas,” which is told from protagonist Henry Hill’s viewpoint, “Casino” tracks two perspectives — that of gambler Sam “Ace” Rothstein (Robert De Niro), modeled on Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, and mobster Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci), inspired by real-life counterpart Tony “The Ant” Spilotro.

Scorsese “saw it as a grand, operatic story,” Pileggi recalls, describing “Casino” as a movie that, “filmwise, was ahead of its time. People weren’t as comfortable with it” as they were with “Goodfellas,” he says. But “they have become more comfortable with it as the years have gone on,” Pileggi concludes.

In part, that’s because “Casino” appeared when two alternate versions of Vegas were battling it out for supremacy: the adults-only gamblers’ paradise versus the family-friendly theme park.

We all know which version of Vegas won that battle — and that what happens here stays here.

But Mob Museum visitors who watch the documentary learn a few insiders’ insights about the making of “Casino” from Pileggi himself.

A rough cut of the documentary includes Pileggi relating the tale of Scorsese filming one on-screen “Casino” murder.

The director complained that the scene didn’t look or feel right. At which point technical adviser Frank Cullotta — a former Spilotro deputy turned FBI informant– promptly stepped in, telling Scorsese, “ ’Of course it’s wrong — that’s not the way it happened,’ ” as Pileggi describes.

So Cullotta demonstrated how the slaying really went down — and wound up re-creating the killing in costume, on camera, for “Casino” — after Scorsese realized that “Cullotta had actually done the murder,” Pileggi says.

“Isn’t that amazing?” the writer reflects. “It actually happened — that’s the murder he confessed to.”

At another point in the production, Cullotta complained about the way “ ’actors are always walking around with guns — you’d think they were holding flowers,’ ” Pileggi recalls. Instead, Cullotta advocated the authenticity of a don’t-just-stand-there-shoot-something policy: “ ’Boom! And you’re walking … ‘ ”

For most of “Casino’s” production schedule, Pileggi was at the Sands, rewriting the script — while the movie was on location at the Riviera, which played the fictional Tangiers casino.

Pileggi says he spent an estimated four years in Las Vegas working on the book that served as “Casino’s” source material — plus additional years collaborating with Scorsese on the movie’s screenplay.

During that time in Las Vegas, “I met a lot of people, a lot of whom were very helpful” — including then-attorney Oscar Goodman, who played himself in “Casino” and, as Las Vegas mayor, promoted the Mob Museum as part of his vision for a revitalized downtown.

So when then-Mayor Oscar Goodman “called and asked whether I thought a (mob) museum was a good idea,” Pileggi gave him a thumbs-up.

“The history is just fascinating,” Pileggi observes. “And as long as Oscar was involved … being Oscar, he actually got the thing going.”

For the museum documentary, Pileggi spent several hours in a New York studio, tracing gangster movie history and trends, from such early 1930s icons as James Cagney (“The Public Enemy”), Edward G. Robinson (“Little Caesar”) and Paul Muni (the original “Scarface”) to such later mob classics as 1972’s “The Godfather” and 1997’s “Donnie Brasco.”

Of “Donnie Brasco’s” title character (played by Al Pacino) Pileggi says in the documentary, “God forbid he’d get a job — because his whole aura would be lost.”

That aura remains a potent draw for actors and audiences alike, who see Las Vegas gangsters as “lovable rogues, not drug dealers,” Pileggi says. “It’s ‘Guys and Dolls.’ ”

After all, “when the airplane and air conditioning made Las Vegas possible,” these “gamblers and high rollers” were “the only people who knew how to run a casino,” Pileggi points out, thanks to their experience running (illegal) gambling operations elsewhere.

Unlike those places, however, Las Vegas made it possible for visitors to gamble legally.

And, if they were lucky, to change their lives dramatically, Pileggi suggests.

“Lefty Rosenthal used to say that the American dream is great wealth — with no work,” Pileggi notes in the mob museum documentary. “That’s the dream of the gangster movie.”

And it’s the dream of the Vegas visitor to this day, Pileggi says, describing Las Vegas as a “city that can actually turn your life around.”

No wonder “it’s an endless reservoir of potential movie material,” in Pileggi’s view. “Vegas is endlessly fascinating.”

And, as the guy who wrote “Casino,” Pileggi ought to know.

Contact movie critic Carol Cling at ccling@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272.