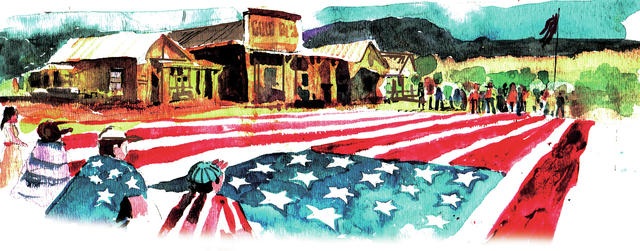

Residents of Gold Point help preserve ghost town

Emblematic of Nevada’s mining history, little Gold Point has experienced many ups and downs since its beginnings in the late 1800s.

Because it has always had a few residents to watch over it during its down cycles, the ghost town retains a few original streets, where about 50 weathered wooden structures remain. A few old sheds and skeletal head frames mark former mine sites near its outskirts.

Gold Point lies about 185 miles from Las Vegas in sparsely populated Esmeralda County. To reach it, drive north on U.S. Highway 95 through Beatty and Scotty’s Junction. At Lida Junction, turn west on state Route 266 and drive about seven miles to Gold Point Road, state Route 774. Turn there and drive southwest about seven miles to the old community.

Gold Point’s history dates to the 1868 discovery of lime deposits on an outcropping just to the west. A short-lived camp called Lime Point grew up in the sagebrush, but its remote location doomed the early enterprise. The discovery of silver near the same location in 1880 brought another short-lived camp, undermined by the same transportation problems.

Discoveries of gold and silver deposits to the north led to the rise of Tonopah and Goldfield in the early 1900s. Prospectors flooded the area after those strikes and re-examined sites such as Lime Point. In 1902, silver ore was discovered there and a new camp called Hornsilver was established. It lasted about a year, hampered by a lack of water and the difficulty of transporting ore.

But improving roads and the arrival of railroads soon made mining in remote parts of Nevada more feasible. In 1905, the Great Western Mine Co. began operations near Hornsilver, where a rich silver deposit generated a small rush. A little gold was also found in the area.

By 1908, many of the early tent buildings had been replaced by wooden structures and about 1,000 people lived in Hornsilver. In May 1908, the opening of a post office put the town on the map and the local newspaper, the Hornsilver Herald, trumpeted its promising future. A booming business district, including 13 saloons, called for the creation of a chamber of commerce. Soon the group was pushing for a railroad spur, since ore still had to be transported 15 miles to the nearest siding at Ralston near present-day Lida Junction.

But that effort failed and Hornsilver soon developed further problems. By 1909, claim jumping and other legal issues resulted in several court cases. Litigation, inefficient mine practices and transportation slowed Hornsilver’s growth. Its population began to dwindle. Mining picked up again in 1915, but the main mining concern wound up in receivership by 1922.

In 1927, gold deposits were found and the area was soon producing more gold than silver, so Hornsilver’s name was changed to Gold Point. New mining ventures kept people working at Gold Point through the Great Depression.

When the nation went to war in 1941, the government assessed the country’s industries, resources and manpower. Gold mining was ordered shut down as a nonessential industry, and miners found other occupations or marched off to war. After the war, mining returned to Gold Point in smaller ventures that persisted until the 1960s, when a major cave-in closed most production.

Serving as postmistress in Gold Point from 1940 to 1967, Ora Mae Wiley saved to town, preventing theft and vandalism when most other property owners had left. Like Wiley, the few residents living in Gold Point today help preserve the town, providing visitors with glimpses of bygone times.

After several years of special fundraising events at Memorial Day, Gold Point will be quiet over the long weekend this year. Visitors are welcome to explore whatever attractions may be open and enjoy guest services still available. For details, call 775-482-4653 or visit goldpointghosttown.com.

Margo Bartlett Pesek’s Trip of the Week column appears on Sundays.