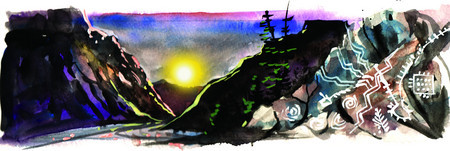

Parowan Gap, petroglyphs deserve a closer look

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places because of its cultural significance, Parowan Gap in Southern Utah displays a treasury of petroglyphs left behind by several native cultures. A form of rock art created by incising designs into stone, the petroglyphs of Parowan Gap cover many flat faces of boulders at the base of the 600-foot cliffs.

A natural pass originally cut into a fractured rising block of mountain by a stream ages ago, Parowan Gap continues its slow changes through erosion by wind and precipitation, particularly when frozen. Ancient passers-by inscribed cryptic symbols in the canyon starting at least 1,000 years ago. Visitors see most of the petroglyphs on the eastern side of the gap.

Unprotected, the rock art suffered at the hands of vandals and looters. The Bureau of Land Management maintains a protective fence around the major rock art site to preserve the remnants of cultures that left no written history. Visitors may photograph and enjoy looking at the ancient designs, but they must do so from behind chain link.

Parowan Gap is a no-fee area with few facilities. From the parking area, stroll past the boulders. Plaques posted at intervals provide some information. Many of the petroglyphs depict animals or animal tracks. Some may map water sources or trails. Other more enigmatic designs may chart astronomical events. Many of the people who gather to witness the light in the canyon at the time of the spring and autumn equinoxes think so. Since the exact meaning of the symbols may never be known, one guess is as good as the next.

Parowan Gap lies a few miles off Interstate 15 west of the historic town of Parowan. Follow I-15 north 195 miles from Las Vegas through Cedar City to Parowan. Reach Parowan Gap by driving west from downtown Parowan 11 miles on Gap Road, 400 North Street. The route passes through a wildlife management area near a remnant lake. Paved for a few miles, Gap Road becomes a graded surface as it approaches the defile through the Red Hills.

The road follows the ancient trails used first by animals, later by nomadic hunters and food gatherers. Later still, when an agricultural people farmed the valley around Parowan establishing several villages, the people still used the trail to reach shallow lakes full of fish and waterfowl. Useful plants grew around their marshy margins.

Although the Parowan Gap might have been known to early travelers using the Old Spanish Trail and perhaps to mountain men in the early 1800s, the first historic mention of it dates from 1849-50. A party scouting the territory for Mormon church authorities in Salt Lake City used the pass while exploring westward.

In 1851, a company of settlers left Salt Lake City to colonize the fertile valley with the good grass and ample water noted by the exploring party. They laid out the grid of wide streets and large lots typical of early Mormon towns. Soon to be called Parowan, the community was the first permanent settlement in Southern Utah since the native farmers left the area several hundred years earlier. Many other Mormon communities in Utah’s “Dixie” soon followed.

Now a county seat and supply center, Parowan boasts about 2,500 residents. Many Southern Nevadans know it only for its access to high mountain recreation areas such as Cedar Breaks National Monument and Brian Head winter sports area. The little town deserves a closer look. Its neatly kept downtown and quiet streets with tidy homes and gardens include many buildings that have been in use for 150 years. Some venerable homes and buildings serve now as museums, bringing pioneer experiences to life for modern visitors.

Take a look at the 1863 Rock Church Museum on Parowan’s main street at the town square. Designed to resemble the tabernacle in Salt Lake City, it served as chapel, meetinghouse, social hall and school. Across the street, an 1857 adobe dwelling houses period artifacts. A small log structure built in 1865 a few blocks away was home and office for Dr. Priddy Meeks, the first physician in Southern Utah. Restoration preserves the sturdy appeal of these pioneer buildings.

Margo Bartlett Pesek’s column appears on Sundays.