Borax and Death Valley have long-standing ties

Borax, a white, crystalline compound widely used in industry, played an influential role in the history of the deserts of Nevada and California. Following discoveries of a form of the compound known as “cottonball” at Tell’s Marsh, Nev., in 1872, Francis “Borax” Smith formed the Pacific Coast Borax Company, now called U.S. Borax. Borax joined gold, silver and other precious minerals in the development of mines, mills, towns and transportation systems in inhospitable locations like Death Valley.

Present and former employees of Pacific Coast Borax gather this week at Furnace Creek in Death Valley National Park to honor the company’s 135 years of existence.

On Monday and Tuesday, ceremonies, a dinner and special tours honor the company that became synonymous with Death Valley.

Nonaffiliated park visitors may join the tours when space is available.

Any time you visit the park, learn more about the importance of borax in Death Valley’s history through exhibits in the visitor center at Furnace Creek and during scheduled ranger talks at nearby Harmony Borax Works.

Death Valley’s headquarters at Furnace Creek lie about 125 miles from Las Vegas. Follow Highway 160 west over the mountains to the town of Pahrump.

A few miles north of the center of town, turn west on Bel Vista, a county road that takes you 30 miles to Death Valley Junction. Note the famous hotel there. It was constructed by Pacific Coast Borax.

The highway from the junction runs 30 miles to Furnace Creek Ranch, passing the beautiful Furnace Creek Inn, an 80-year-old resort originally built by Pacific Coast Borax.

Following Borax Smith’s Nevada discoveries, prospectors fanning out over the deserts kept an eye open for borax crystals. In Death Valley, Aaron Winters and his wife applied a sulfuric acid and alcohol test to some crystals they found.

Winters reportedly exclaimed, “It burns green, Rosie. We’re rich!” They sold their claim for far too little to William T. Coleman in 1881. He began Harmony Borax Works to exploit the acres of cottonball borax ore he had acquired. Soon encountering financial difficulties, he sold out to Borax Smith’s growing company.

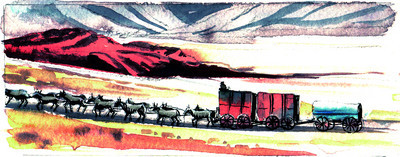

Getting the product to market posed problems, as the nearest railroad was at Mojave, Calif., 165 miles from Death Valley. Pacific Coast Borax crews cleared a rudimentary route. Smith ordered enormous wagons to be built in Mojave.

These unusual wooden vehicles carried tons of ore at a time. They had seven-foot wheels on the back and five-foot wheels on the front. Made of oak, the wheels had iron “tires” an inch thick and eight inches wide. The company assembled teams of sturdy mules, huge draft horses and experienced teamsters.

Two teams of 10 animals each were hitched to two wagons followed by a third conveyance carrying a 500-gallon water tank. Between 1883 and 1889, the 100-foot long hitch made 20-day round-trips, carrying 20 million tons of ore without the loss of one mule or breakdown of a single wagon. The “20-mule teams” made borax a household word across the country and an iconic symbol of the company around the world, must like the Budweiser Clydesdales.

The famous team and wagons became the subject of a 1940 Hollywood film. They became the stuff of legends through the popular radio and television program, “Death Valley Days,” which started on radio in 1930.

Borax itself grew in importance from simple household cleaning products and patent medicines a century ago to uses in myriad industries today.

After the teams retired because of improved rail and road connections, they still made special appearances. They came to the 1906 World’s Fair, President Wilson’s 1916 inauguration and the 1937 opening of the San Francisco Bay Bridge. Old-timers in Las Vegas recall the participation annually of the borax team and wagons in the Helldorado parades following a two-week journey.

A favorite entry in many Rose Bowl Parades, they last appeared in 1999. Early this fall they made an appearance at the visitor center of the U.S. Borax mine at Baron, Calif., in honor of the company’s 135 years.

Margo Bartlett Pesek’s column appears on Sundays.