Danny Gans: How an unknown impressionist became the biggest act on the Strip

superstar

It was easy to assume Las Vegas had seen it all, at least twice, during its first 90 years.

Performing bears. Topless ice skaters. For a while, people couldn’t get enough of watching the mushroom clouds from nearby atom bomb tests.

Seemingly everything that could possibly pass as entertainment had been tried.

Then came the city’s 91st year and the arrival of a singing impressionist with virtually no name recognition — even his nickname, “The Man of Many Voices,” was underwhelming — who became the biggest act in town seemingly on Day One.

You could build a thousand Las Vegases on a thousand planets and still not produce a less likely superstar than Danny Gans, whose death on May 1, 2009, left a hole in this city that’s yet to be filled.

Gans connected with locals, celebrities

“No one’s ever been as successful doing impressions,” Rich Little once told us of Gans.

He also perfectly summarized the strange place Gans occupied in the entertainment ecosystem. “In Butte, Montana, they never heard of him. But in Vegas, he was a superstar.”

Gans was almost impossibly charismatic. He had to have been to attract turnaway crowds to see him perform both sides of the Nat King Cole-Natalie Cole “Unforgettable” duet from 1991 and both the Henry Fonda and Katharine Hepburn parts in a scene from 1981’s “On Golden Pond” — in this millennium.

Other signature pieces — of approximately 200 voices in his arsenal, he’d deploy around 60 per show — included achingly poignant tributes to George Burns and Sammy Davis Jr., an Al Pacino monologue from 1992’s “Scent of a Woman” and a bit with Kermit the Frog.

What separated Gans from most other impressionists was his singing ability. When the NBA All-Star Game came to the Thomas & Mack Center in 2007, of all the entertainers up and down the Strip, he sang the national anthem.

Gans connected with locals in a way few headliners have, yet he drew celebrities by the boatload.

Benjamin Netanyahu came to see him. Regis and Joy Philbin celebrated their 38th anniversary at his show. He impersonated Michael Jackson, Sylvester Stallone, Tony Bennett and Dustin Hoffman while they were in his audience.

The year “Titanic” was released, Leonardo DiCaprio brought Bar Rafaeli to Gans’ show on a date — then brought her backstage!

Even Gans’ daily life made it into Norm Clarke’s celebrity column, whether it was eating with his family at Benihana or the Carnegie Deli or sinking a bunker shot that “produced a standing ovation from many diners having lunch at the Wynn’s Country Club Grill.”

In the 15 years since his passing, Las Vegas still hasn’t seen anything quite like Gans.

Trading the road for Las Vegas

“I think one of the reasons I have a chance of making it here is that the audience is middle-of-the-road: moms and pops, people in their 20s and 30s and senior citizens,” Gans told us ahead of his 1996 debut at the Stratosphere. “My act is geared toward people of all ages. People who read People magazine, listen to Top 40 or oldies stations or have a love of old movies.”

Gans wasn’t a newcomer by any means. He turned to comedy and impressions after his minor league baseball career ended with a severed Achilles tendon in 1978.

A Nov. 12, 1979, column by the Review-Journal’s Forrest Duke mentions a show called “Palace Playmates” was opening the next day at the new Nevada Palace on Boulder Highway. Produced by Steve Rossi, the show was to feature impressionist Danny Gans, illusionist David Douglass and the Shirley Freeman Dancers performing 18 times a week. “Palace Playmates” was never mentioned again in our pages.

Gans opened for Lola Falana at the Dunes at the end of 1983, which led to our Bill Willard opining that the entertainer’s “scavenging of celebs for his impressions and coruscating results put him into the upper class of Xeroxers, to be watched.”

He drew raves in May 1991 when he opened for Joan Rivers at the Desert Inn. The following year, Gans marveled at seeing his name on the Las Vegas Hilton marquee when he opened for Bill Cosby with a 45-minute set. “Gans pretty much stole a show from Cosby,” we wrote, adding that the comedy legend called him potentially the next Sammy Davis Jr. — back when an endorsement from Cosby was considered a positive.

Gans really honed his craft, though, by performing more than 100 corporate gigs a year.

“I sat down with enough corporate producers and asked what kind of act would be a big success,” Gans told us in 2000. “They said, ‘Middle America wants comedy, but they’re afraid comics are going to get dirty.’ ”

“If you can be funny,” Gans said he was told, “be musical and appeal to everyone from (their) late 20s to early 60s, you’ve got it.”

Calculating? Sure. But it worked.

A brief run at the Neil Simon Theatre in the fall of 1995 led to reports of a one-year offer for him to remain on Broadway, but Gans also was drawing interest from Las Vegas.

“I made a stance and said in prayer with my wife, ‘I want to be a family man and put my family first in my life,’ ” Gans told us in that same 2000 interview. “And I did that by turning down Broadway. And from the time I did that, this touch has been upon my career.”

Putting his family first

Gans’ day job as a family man to his wife, Julie, and children, Amy, Andrew and Emily, attracted the attention of legendary television producer Aaron Spelling. He spent years trying to get Gans to commit to an autobiographical sitcom about a devout Christian husband and father living and working in “Sin City.” But becoming a TV dad, Gans realized, would mean untold hours away from his actual family.

“There’s a time and a place for everything,” he told us in 2002. “How many more (baseball) games do I have with my son? Those things are so much more important to me than having my face on the cover of TV Guide.”

Despite having some small acting roles before landing in Las Vegas, most notably in “Bull Durham” and on the late-night crime drama “Silk Stalkings,” Gans tended to shy away from TV once he was here. That included talk shows.

“If I’m already selling out, what’s the purpose of doing television?” he asked in a 2006 interview. “It’s better for me to have the word of mouth and the buzz that you have to see this show.”

Instead of talk show appearances, he said, “I’d rather spend that three hours to take my daughter to lunch or play golf with a friend.”

When he wasn’t golfing, Gans spent most days at home going over notes from the previous night’s show. Some of those were provided by his daughter Amy, who worked as an usher and gathered intel from the audience on whether new bits were working.

“It has been great to play such an integral part in my children’s lives,” Gans wrote in a guest column in 2002. “When I was on the road 250 days a year, I was missing out on the joys and frustrations of being a parent.”

He wasn’t universally beloved

This is as good a place as any to say that, despite his popularity, Gans wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea.

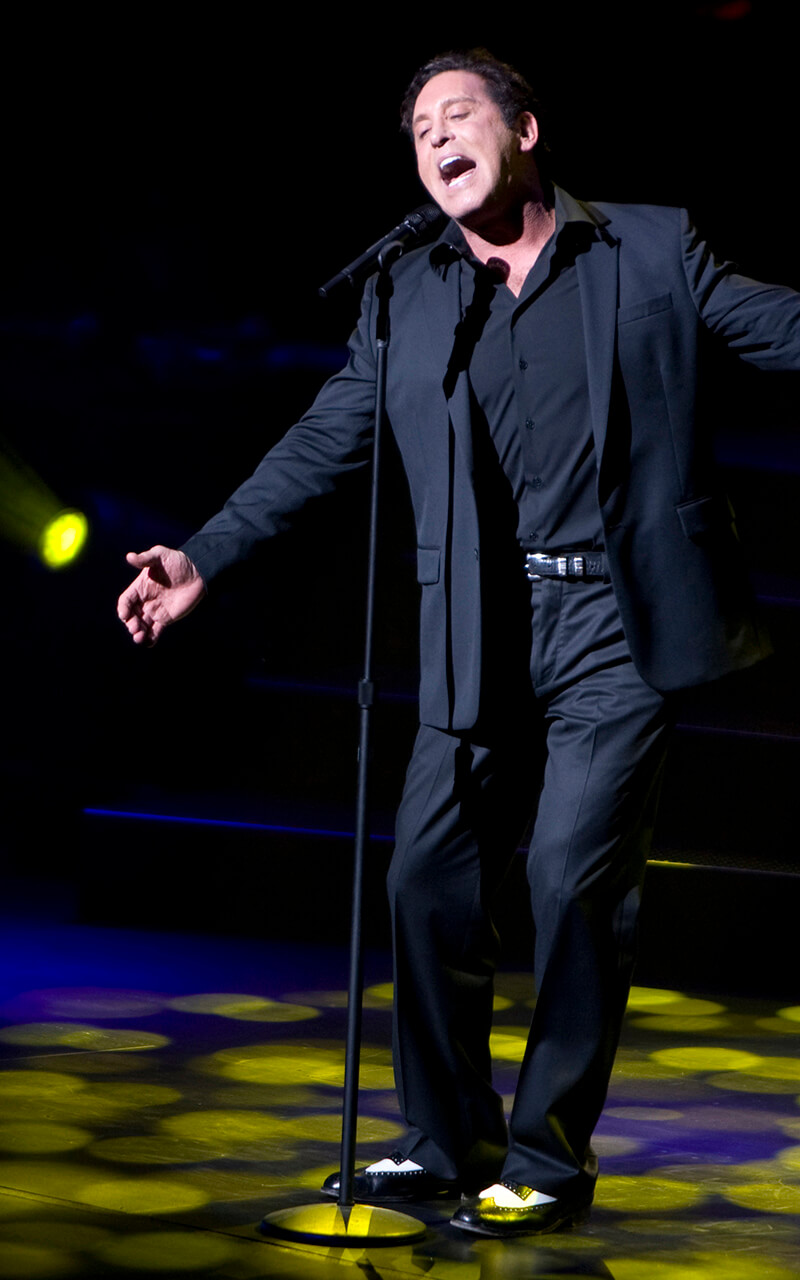

His reputation as a goody-two-shoes — those shoes being the black-and-white spectators he wore, with red socks, during every performance — just rubbed some people the wrong way.

Younger, hipper acts poked fun at Gans, and the city’s alt-weeklies often were brutal.

He didn’t always get along with his bosses. Kerfuffles over his placement on The Mirage marquee spilled into the mainstream.

Critics howled that the updates to his act were few and far between.

The way Gans wouldn’t talk for long periods to save his voice for the show could come off as a bit odd. In 2000, he told an interviewer that he and his kids were learning sign language to communicate during those times.

And, roughly six weeks before his death, a roundup of major water users listed him as the fifth biggest consumer in the valley, having used 7.9 million gallons in 1998.

The most expensive show in town

Announcing Gans’ Stratosphere show, entertainment columnist Michael Paskevich wrote, “if the show goes as planned, it could result in one of those now-rare situations in which a Vegas-based act becomes a household name.”

Gans opened May 16, 1996, in the 650-seat Broadway Theatre before signing a three-year deal with the Rio and moving to its 700-seat Copacabana Showroom on Jan. 22, 1997. Two months later, Paskevich declared Gans was “the hottest thing to hit Las Vegas since the invention of August.” By that summer, Gans was getting third billing in ads for ticket brokers, behind only Tyson vs. Holyfield II and the NBA Finals.

Those brokers weren’t the only ones overcharging fans. In November 1997, Gans sued the Rio, claiming the hotel increased his ticket prices without his consent.

“I wanted my show to be for the masses,” Gans said at the time, “not just the privileged.”

The lawsuit was withdrawn the next day, but the price hikes didn’t stop. By May of 1999, the Rio had raised his ticket prices five separate times, taking them from $34.95 when he opened to $99, making his the most expensive show in town. (“O” had the top ticket price at $100 but also had seats for $90.)

The week that final hike went into effect, $99 would have gotten you a ticket to see the Wayne Newton and Penn & Teller shows at the MGM Grand, and you would have had change left over.

“There are people who have a lot more name recognition than I do that you can see for less,” Gans told us in 2006, still sensitive about his ticket prices. “There’s a good amount of pressure knowing the tickets are a hundred bucks, and they can go see ‘Ka’ for the same amount of money or less. Here’s a guy trying to make a decision: ‘I can go and see this huge spectacle, or I can see one guy in front of a seven-piece band.’ ”

After three years at the Rio, Gans moved to The Mirage.

His ticket price dropped to $67.50.

You couldn’t escape Danny Gans

Gans was pretty much everywhere in the valley.

His arrival at the Stratosphere was accompanied by ads atop more than 120 taxis and in nine city bus shelters, commercials played on TV and every 10 minutes at the airport baggage claim, and videos ran throughout the hotel on a loop.

During a show at Luxor in 2005, Andrew Dice Clay took aim at the phenomenon. Before you got to town, he said, you’d never heard of Gans. Then, once you land, you’re confronted by all the advertising. “By the time you get to your room,” Clay joked, “you’re in a panic to see Danny Gans.”

Gans himself was nearly as ubiquitous. Over the course of just two months in 2005, he:

Performed a benefit show for the Lili Claire Foundation.

Performed a benefit show for the Nevada Childhood Cancer Foundation and Homeless Shelters of Nevada.

Hosted a dinner and show for Opportunity Village.

Hosted a dinner and show for his Danny Gans Junior Golf Academy.

Hosted the annual Danny Gans’ Partee Fore Kids charity pro-am golf tournament.

Led the third annual Danny Gans Run for the Rainforest to benefit Vanderburg Elementary School’s biosphere.

Donated tickets to his Sept. 11 show to local active-duty firefighters and police officers.

And raffled off his 2001 Z06 Corvette, in addition to donating $100,000, for Hurricane Katrina victims.

The Rocky Balboa of Vegas

“It was really a fairy tale,” Gans said of his rapid ascent in Las Vegas ahead of his March 31, 2000, opening at The Mirage. “It doesn’t get any better than this. The theater, where I’m sitting on the Strip, right in the heart of it all.”

That theater and its 1,260 seats were converted from a ballroom at a cost of $15 million. It was modeled after two of Gans’ favorites, the Apollo in Harlem and the Fox in St. Louis, and it bore his name.

Gans called it home for more than eight years, until he was lured across the street to Wynn Las Vegas and its 1,500-seat Encore Theater.

He closed out his run at The Mirage on Nov. 22, 2008, ending his 1,639th show there with a performance of “What a Wonderful World” that included his takes on Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Ray Charles, Willie Nelson, Tony Bennett, Kermit the Frog, George Burns and Louis Armstrong.

The next afternoon, his face was replaced on The Mirage’s marquee by that of Terry Fator, the “America’s Got Talent” winner who was inspired to start singing his impressions, through his puppets, after seeing Gans’ show at the resort.

“I think I’m a much better entertainer than I was when I first came to town,” Gans told us ahead of his Feb. 10, 2009, opening at the Wynn. “I know much more. My repertoire’s grown. I’m a better singer and a better comedian. I’m a better performer, just because I’ve been doing it for 12 years longer.”

Gans sounded energetic and excited about the opportunity ahead of him.

“I take a lot of pride in the fact that I’m still here,” he said in that interview. “I feel like I’m kind of the Rocky (Balboa) of this town. I’m still standing, still drawing. As long as I can do it, why not keep doing it?”

‘This will always be Danny Gans’ room’

Three months later, on May 1, Las Vegans awoke to the shocking news.

Gans, 52, had died early that morning in his Henderson home, the result of hydromorphone toxicity due to chronic pain syndrome.

Julie Gans and the kids moved to California shortly after he died. Garth Brooks, lured out of an eight-year retirement by Steve Wynn, moved into the Encore Theater on Dec. 11 for a four-year acoustic residency. “This will always be Danny Gans’ room,” Brooks regularly told audiences.

In the end, Gans was named best all-around performer 11 times by the Review-Journal’s Best of Las Vegas. The last honor came in 2009, with the first in 1997 during his initial year of eligibility.

“It’s hard for me to leave a stage,” Gans told us before that first Stratosphere show. “I want (the audience) to leave and say, ‘Wow!’ And I want them to go through all the emotions that I go through in a show.

“I know the idea is to leave them wanting more, but I always want to give them more.”

Contact Christopher Lawrence at clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567. Follow @life_onthecouch on X.