Artist tries to understand her tragic father through exhibit

Dad was a murderer.

Yet the murderer was still Dad.

“The love can still exist with this really horrible, hateful reality at the same time,” says 26-year-old Las Vegas artist Noelle Garcia. “I had really hero-ized him in my head. I hadn’t known about the murder until last summer. (Her mother) didn’t tell me, and there was good reason for protecting us.”

The American Indian daughter of a convicted killer-turned-parolee-turned-parole violator-turned-prisoner again, Garcia harbors complex emotions toward her father, Walt, which are explored in “What You Left Me: Creating Dad Through Artifact” at the Winchester Cultural Center Gallery.

“We knew he was in prison, but we didn’t know what for. I was hoping when I ordered his records that it would be for something like drunk driving or bouncing checks. When I found out this information, it was really awful.”

A personal quest courageously turned into a public exhibition about a private relationship, “What You Left Me” takes Garcia away from her usual work as an artist and transforms her into a family archaeologist. Unearthing photos, documents, prison records, clothing and other remnants, she explores the life of an estranged member of the Klamath Tribe who considered himself a cowboy, fathered children by several women and murdered a man in the 1950s when he was 25 years old, initially serving 20 years before a dizzying round of paroles, violations and prison returns.

“The story that unfolds as you walk through the space is very tragic and conflicted,” says Wendy Kveck, director and curator of the Clark County Galleries. “Though the artist is honoring her father and attempting to develop a relationship with him through her research, she is not condoning his behavior or his crime.”

Part of what she termed “a last-minute family” her dad started in his 50s after numerous incarcerations, and raised in the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, Garcia explains the violence at the heart of Walt’s story:

“The details are fuzzy, but he got into a fight with a fellow ranch hand, he pulled out a shotgun, shot him in the head and dumped his body in the Elko dump. (After his release), one of the provisions of his parole was that he couldn’t drink, and he was always back in for that,” she says.

“I didn’t live with him that often, but when he was sober he was quite affectionate, and I really valued that relationship with a parent. He was very protective. But he was drunk quite often, and then he hit people and did lots of awful things, more with my mom and younger siblings who were very sick. He was always very cruel to them, and I think it’s because they were weak.”

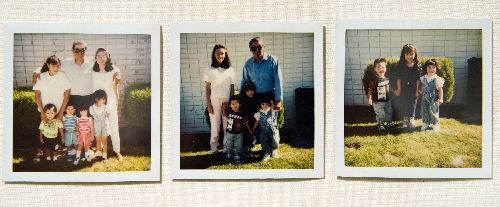

Paroled one last time in 1999, he died a year later at age 63 and was interred in the Klamath tribal burial grounds. His life is laid out in a display that includes photos taken from family visits in front of the stark brick walls of prison buildings, the prisoner smiling, arm slung over the shoulders of family members. There’s even one of him posing with the prison baseball team.

Shown as well: his marriage certificate; writings declaring his devotion to Christianity that developed after his incarceration; a buckskin purse made for his wife, Rose; photos of him competing in rodeos, serving in the military and attending Indian boarding schools as a youngster, forcibly removed from his home when the Klamath tribe was terminated in the 1940s by the federal government (it was re-established in the 1980s) to assimilate into the general white population.

The effect is contradictory and complex — a bad man with some redeeming qualities, or perhaps a basically good man with tragic flaws, much of them stemming from alcoholism and trying to live a dignified life as an American Indian in this country — but then you come across a notice of subpoena to Noelle’s mother and older sister to testify at a parole revocation hearing.

“It was when he was drunk and my mom was on bed rest, pregnant with (her twin sisters), and he burned me with a cigarette,” Garcia says. She was 2 at the time. “They called Social Services, and this was a consequence of that.”

Another photo was taken at her parents’ 1984 wedding ceremony in Virginia City, the story behind it providing a shock for their daughter. “It was kind of a shotgun wedding,” she says. “If you notice, my mom was in a maternity shirt there. I didn’t know it was me until I ordered the document and I said, ‘Mom, you know this was awfully close to my birthday.’ ”

Beyond the personal aspects of the exhibit, however, Garcia says it is “socially relevant because of showing how Native Americans are objectified in museums, rather than seen as contemporary living people. … I became very white when I moved to Las Vegas, very Americanized, but I also have such a rich Native American background.”

One document she discovered for her father, but exemplifying a social indignity to the entire community, left her angry — a “certificate of blood” required for all tribes for an American Indian to be recognized as such. “To receive any benefits from the government or to apply for scholarships, you have to have a pedigree, which is really offensive,” she says. “You don’t have to prove you’re black or Jewish, but you have to prove you’re an Indian.”

Listing her father as one-half Klamath Indian and one-half Mexican on the certificate reveals another contradiction in his convoluted psyche. “It was a joke, because he was prejudiced and would say horrible things about Mexicans.”

Visitors, Kveck adds, “have expressed a shared experience, whether it is a shared Native American heritage or the loss of a loved one, people have connected with the exhibition on many levels.”

Protector and abuser. Alcoholic and Christian. Man and murderer.

And one daughter attempting to comprehend how they combined to create the tragic emotional storm she called Dad.

Contact reporter Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld@ reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0256.