Was AI a catalyst in the Cybertruck explosion? Experts weigh in on ChatGPT’s role

Experts are divided on whether the role ChatGPT played in plans to explode a Tesla Cybertruck outside the Trump International hotel on Jan. 1 should raise concerns about the safe use of artificial intelligence, but many agreed the New Year’s Day explosion highlights the fact that policies safeguarding the use of AI are lagging behind as technology races ahead.

U.S. Army Master Sgt. Matthew Livelsberger asked ChatGPT a series of questions about how to acquire and use explosive materials the day before he rented a Cybertruck in Denver and began his journey to Las Vegas, where he fatally shot himself in the head right before his Cybertruck exploded, authorities said. Seven people were injured in the explosion.

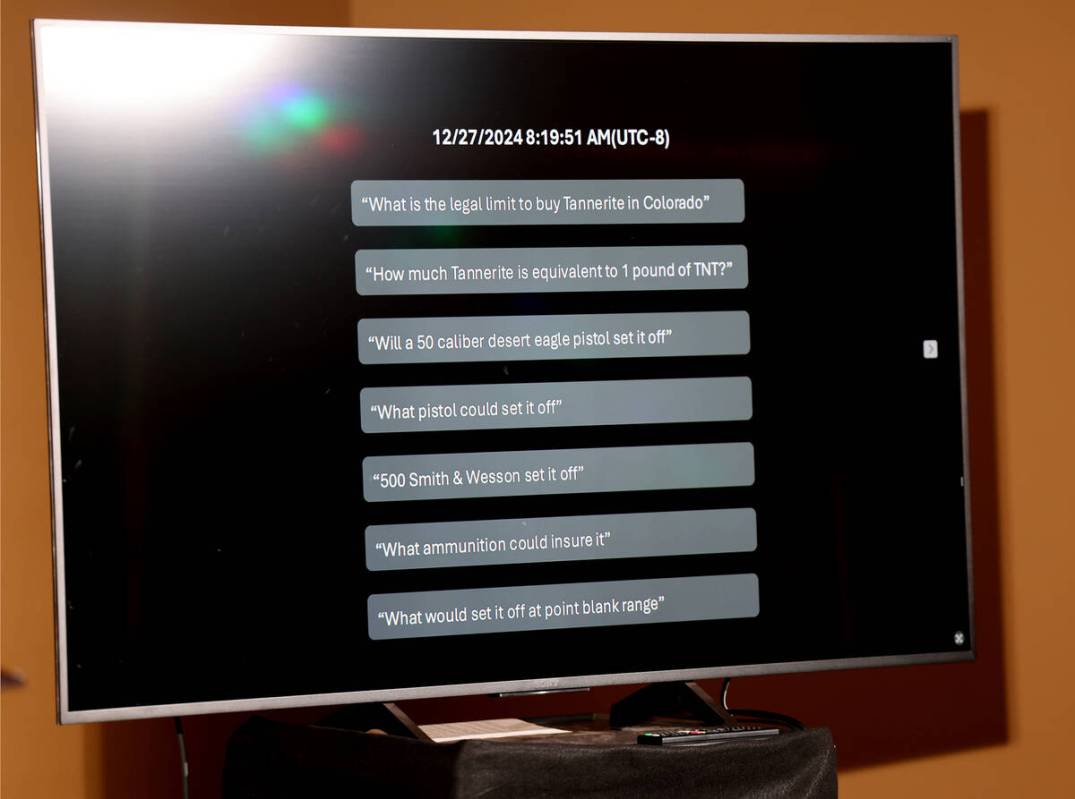

Livelsberger’s AI queries included questions such as “What is the legal limit to buy Tannerite in Colorado” and “What pistol could set it off,” according to the Metropolitan Police Department. Tannerite is a brand of reactive rifle targets that, if shot, explode.

When a Review-Journal reporter asked ChatGPT the same questions Livelsberger did, the software provided in-depth answers to 21 of the 22 queries. The one question that ChatGPT didn’t answer, citing a violation of its usage policies, related to what ammunition would be needed to make sure the explosive materials were set off.

Blowing up the Tesla Cybertruck was a prosecutable crime, emphasized Wendell Wallach, a bioethicist and author whose work focuses on the ethics and governance of emerging technologies. Wallach wasn’t surprised by Livelsberger’s use of ChatGPT and said “it was only a matter of time” before ChatGPT was enlisted for such help, but he said he was concerned about a lack of accountability.

“The crime is committed with accomplices, but the accomplices are either not human, or they’re humans who are sheltered from liability because this was all filtered through a computational system,” Wallach said.

Experts explained that ChatGPT itself can’t know that it’s being asked dangerous questions. It can only read the language and return the most statistically probable response. All of the safeguards put in place to restrict what the chatbot will or won’t say have to be established by its developers.

“The corporations sit there with the mantra that the good will far outweigh the bad,” Wallach said of the development of generative AI. “But that’s not exactly clear.”

‘Information already publicly available on the internet’

A statement shared with the Review-Journal from OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, said, “we are saddened by this incident and committed to seeing AI tools used responsibly. Our models are designed to refuse harmful instructions and minimize harmful content.”

“In this case, ChatGPT responded with information already publicly available on the internet,” the OpenAI spokesperson said.

This point was key for Andrew Maynard, a professor at Arizona State University whose work focuses on navigating advanced technology transitions. “From what I can see beyond just using the tool, there’s nothing there that he couldn’t have found elsewhere,” Maynard said.

While Maynard said he feels there are potential dangers with platforms like ChatGPT, Livelsberger’s interactions with the chatbot didn’t rise to that threshold. “There seems to be no evidence that there is something fundamentally wrong with ChatGPT,” he said. If the chatbot had procured hard-to-get information about building a biological weapon, then Maynard said he’d worry.

The question of whether easy access to potentially harmful information is a problem predates generative AI, according to David Gunkel, a professor at Northern Illinois University who also describes himself as a philosopher of technology. “Three or four decades ago, you could have asked the same question about the public library,” Gunkel said.

The difference between ChatGPT and a search engine lies in the chatbot’s speed and user interface, Gunkel explained. If Livelsberger had used a search engine to ask the same questions, he would have had to sort through the list of results provided and read documents to find the specific pieces of information he was looking for.

When the Review-Journal asked ChatGPT the same 22 questions as Livelsberger, it took less than eight minutes for the chatbot to directly respond to all of them.

‘Policies will evolve based on what we learn over time’

Emma Pierson, a professor of computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, who is affiliated with the Center for Human-Compatible AI, said that the kind of content ChatGPT provided Livelsberger with, which included lists of guns that could ignite explosive materials, seemed “straightforwardly like the kind of things you want the model to just shut down.”

If OpenAI doesn’t want its models providing dangerous information, and the software provides it anyway, this is “bad in and of itself,” Pierson said, because it suggests the controls put in place by the company to prevent this kind of information are not sufficient.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT usage policies, which were last updated Jan. 10, 2024, dictate that the models are trained “to refuse harmful instructions and reduce their tendency to produce harmful content.”

“We believe that learning from real-world use is a critical component of creating and releasing increasingly safe AI systems. We cannot predict all beneficial or abusive uses of our technology, so we proactively monitor for new abuse trends. Our policies will evolve based on what we learn over time,” state the policies, which are available on OpenAI’s website.

OpenAI did not respond to questions about whether or not the policy will be changed in the wake of the Cybertruck explosion.

It goes against OpenAI’s usage policies to promote or engage in illegal activity or use OpenAI’s services to harm oneself or others, including through the development or use of weapons, according to OpenAI’s website.

Gunkel said he feels that OpenAI’s ChatGPT was rushed to market before the product underwent comprehensive in-house testing. “An explosion of this sort is big and dramatic,” Gunkel said, but there are “smaller things” that point towards his conclusion — namely biases in the algorithm or hallucinations, which are things that “sound good, but they’re not correct,” he said.

“There’s been some talk about putting the brakes on AI,” Gunkel said. “These things sound good, but they don’t generally work in practice.”

Multiple experts agreed that the right path forward is to get out in front of the challenges presented by generative AI and make sure that laws and policies are in place to prevent against possible harms.

Learning moment for law enforcement?

For Corynne McSherry, legal director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, concerns surrounding Livelsberger’s use of ChatGPT are overblown. “The anxiety about the use of ChatGPT is a reflection of the general anxiety that surrounds it,” she said. “ChatGPT is a tool.”

McSherry said that public anxiety surrounding the use of generative AI ends up “distracting us from a more important set of questions,” such as why Livelsberger did what he did. “These are harder questions but probably more important ones,” McSherry said. They are also questions that authorities were still trying to answer, Metro Sheriff Kevin McMahill said in a briefing Jan.6.

Nonetheless, McMahill said that the use of ChatGPT in Livelsberger’s plans was a “concerning moment.”

“This is the first incident that I’m aware of on U.S. soil where ChatGPT is utilized to help an individual build a particular device,” McMahill said in the Jan. 6 briefing. “It’s instructive to us.”

McMahill added that he didn’t think it would have been possible for Livelsberger’s ChatGPT searches to have raised any flags prior to the explosion. This kind of technology is something that Maynard suggested people start considering, if they’re not already.

“It’s absolutely critical that law enforcement groups and organizations are up to speed with how people are using these platforms and how they might potentially use them, otherwise they are going to be blindsided,” Maynard said. “Simply ignoring it, or not moving fast enough, puts them in a dangerous and difficult position.”

Contact Estelle Atkinson at eatkinson@reviewjournal.com. Follow @estelleatkinson.bsky.social on Bluesky and @estellelilym on X.