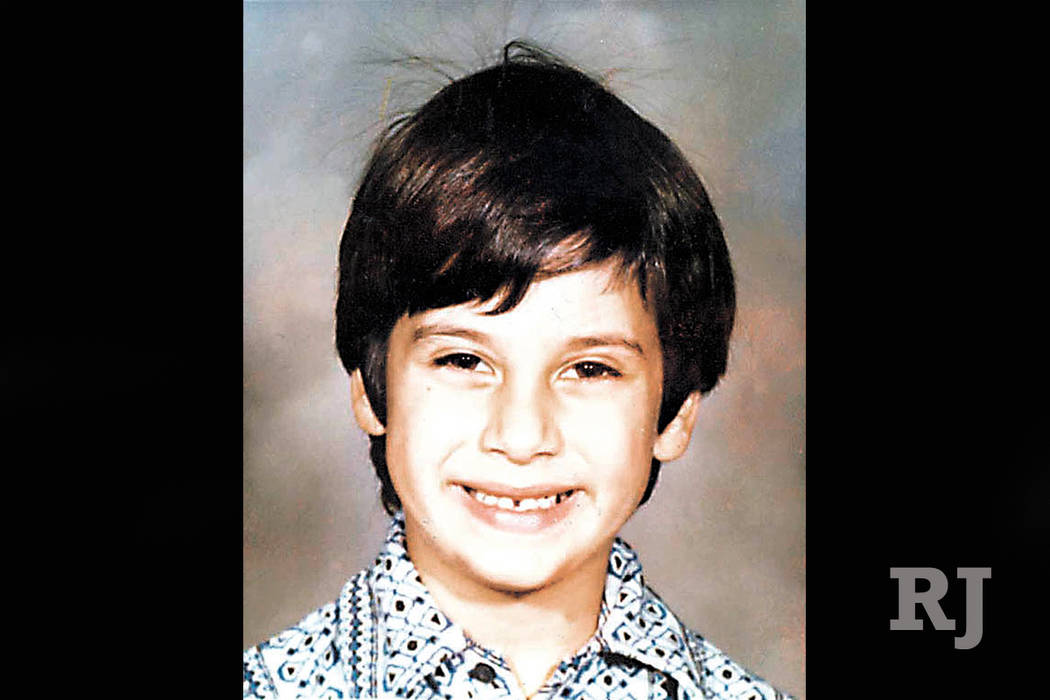

Las Vegas boy’s kidnapping case remains open, 40 years later

The 1978 kidnapping of 6-year-old Cary Sayegh has teetered between solved and unsolved for 40 years.

Authorities do not consider the case a whodunit. Early in the investigation, Jerald Howard Burgess — a man who already had convictions for tax evasion and sexual assault — emerged as the suspect.

Even today, nearing the 40th anniversary of Cary’s abduction on Oct. 25, 1978, former investigators involved in the case say they have no doubt that Burgess, then 41, was behind the child’s disappearance from his Hebrew school.

A jury disagreed and acquitted Burgess long ago. Still, the brown-eyed boy’s case remains open with both the Metropolitan Police Department and the FBI, and it won’t be closed until investigators can answer a question that has lingered for four decades:

Where is Cary’s body?

“I was always hoping that before he died, Burgess would tell us where the body is — to just show a fraction of remorse,” former Metro juvenile Detective David Dunn said during an interview in early October as he sat back in an armchair inside his living room. “I’m talking about the case today because you never know what it’s going to take to stir somebody’s memory. Different people see things differently.”

One day after his acquittal in 1982, Burgess said law enforcement had used him as a “handy suspect” to remove pressure from their backs, according to a Review-Journal story at the time.

“I knew I was innocent, and I didn’t need anybody else to judge me,” Burgess declared.

Burgess, now 81, still lives in Las Vegas with his wife of 29 years, Phyllis.

On a recent Thursday, exactly two weeks ahead of the crime’s anniversary, Burgess sat on a chair in the driveway of his humble one-story home in the western valley, less than 10 miles from where Cary was last seen, and leaned against a walker as his wife cut his thin, white locks.

“We have people visiting,” Burgess said to his wife as a Las Vegas Review-Journal reporter and photographer approached the driveway. “Who are they?”

When Phyllis Burgess learned that the visitors had come to ask about the kidnapping, she placed one hand on her husband’s shoulder and said, “We’re not talking about that. We have nothing to say.”

The disappearance

Cary was the son of Sol and Marilyn Sayegh, the wealthy owners of the Carpet Barn. The boy was taken around lunchtime from the playground of the Albert Einstein Hebrew Day School at 1600 E. Oakey Blvd., near downtown Las Vegas. Today, a charter school operates at the same location.

Hours after the kidnapping, the Sayeghs’ home phone rang. Their neighbor, Geraldine Blutter, who was at the house with the family, answered.

“I’ve got your kid,” said a man with a low, raspy voice. The caller thought Blutter was Cary’s mother, according to Review-Journal reports at the time.

Blutter later would testify at Burgess’ kidnapping trial that she recognized the caller’s voice as his, and a voice expert who analyzed the recording also testified that there is a “big probability the unknown voice and the voice of the defendant are the same,” news reports at the time said.

The man demanded $350,000 in small, unmarked bills in exchange for Cary’s safe return and warned her not to call police.

News reports at the time said the ransom call was for $500,000, but an FBI spokeswoman this month confirmed the demand was for $350,000.

The man said he would call back in a few days with instructions, but the call never came.

The crime rocked the valley and its population of about 400,000.

And so began one of the most exhaustive searches in Southern Nevada history. It involved 50 FBI agents, which, at that time, was the largest number of agents to work a single case in Las Vegas.

Exhausting all leads

Among those agents was Johnny Smith, who kept an eye on Burgess for weeks after he was identified as a suspect.

On a recent morning, the retired agent sat in his kitchen as he thought about the case and the boy.

“We did all kinds of things to find him,” he recalled as he looked out a large bay window. “The whole office dropped everything we were working on until there were no more leads to work.”

The search had both the FBI and Metro combing the valley for traces of Cary. For months, they worked around the clock, chasing leads, scouring through open areas of desert and searching water wells.

They even consulted a psychic for clues, recalled Dunn, the former Metro detective. Many details of the case have been lost to time, but both Dunn and Smith remember Peter the psychic.

“We’d try just about anything just to get the boy back,” Dunn said.

For the first 10 days after the kidnapping, Dunn stayed with the Sayeghs, keeping watch over them and monitoring any incoming phone calls.

He got to know the family well during that time, but it was the intense search for Cary that cemented the unexpected but lasting friendship with Sol Sayegh, Dunn and Smith.

“This has just ruined his life,” Smith said of the father. “He’d like to find the body for some closure.”

Through Smith, Sol Sayegh declined to speak with the Review-Journal for this story, and attempts to reach Cary’s mother and siblings were unsuccessful. The parents divorced years ago.

‘Emotional roller coaster’

Immediately after the kidnapping, Burgess caught the attention of the FBI and Metro when he led investigators to one of the boy’s shoes in a desert area.

Burgess said that he had been contacted by an anonymous person to act as the go-between for the kidnapper and Cary’s parents.

“He told us that this person told him where to find the shoe,” Smith recalled.

By early 1981, Cary was presumed dead. Still, without a body, a Clark County grand jury indicted Burgess in March 1981 on charges of first-degree kidnapping and obtaining money under false pretenses. At the time of the indictment, he already was serving state and federal time for unrelated tax evasion and sexual assault charges.

“Everyone knows it’s hard to convict without a body, but we were confident at the time they would get a conviction,” Dunn said.

According to news reports, then-Chief Deputy District Attorney Mel Harmon told the jury during his closing argument that Burgess took the Sayeghs on an “emotional roller coaster” by pretending to be an intermediary with the kidnappers, when, in fact, “he was the real kidnapper.”

“Can you think of anything more despicable than to prey on the agony and anguish of the parents the way this defendant has done?” Harmon asked the jurors.

But defense attorney Frederic Abrams said in his closing argument, “They don’t have a body. They don’t have a victim here to tell you anything. They don’t have anything.”

The State Bar of Nevada website lists Abrams as deceased.

The trial produced emotional testimony from Sol and Marilyn Sayegh.

Bonnie Kaufman, who was the playground supervisor the day Cary was kidnapped, testified that she saw Burgess on the school grounds talking to Cary before he was taken. And a former business partner testified that he saw Burgess, minutes after the abduction, in a car with what appeared to be a child on Sahara Avenue near Eastern Avenue, about a mile from the school.

Smith said the trial “got a lot of the evidence out there that wouldn’t have been available to the public.”

But in February 1982, after a roughly three-week trial and four days of deliberation, a jury of six men and six women found Burgess not guilty.

One of those jurors was Randy Goodwill, who was 22 at the time.

In 2001 he told the Review-Journal, “I never heard anything that the prosecutors presented to me that would lead him to be guilty.”

During the recent interview, Smith said, “There’s always that doubt if you’re one of the jurors. You say, ‘Well, is this kid really dead? Is this kid really kidnapped? Did he run away on his own?’ And that’s what happened. And in a criminal trial like that, it has to be unanimous. Just one juror could say, ‘I’m not positive.’”

Targeting the suspect

Burgess was paroled in his federal case in December 1983, then entered the Nevada prison system to serve out the remainder of a 15-year sentence for sexual assault. He was released in 1989.

But he remained under suspicion in Cary’s kidnapping.

In 1999, the investigation was revived with the hopes of finding the boy’s body. By then, the case had been inactive for nearly two decades.

FBI agents and Metro officers targeted Burgess, who ended up selling a .22-caliber handgun with a silencer and some ammunition to an undercover agent as part of a deal arranged through an FBI informant.

Burgess had talked to the informant about disposing of bodies. During those discussions, Burgess said one could get rid of a body by placing it in a steel drum, filling it with acid and welding it shut. And at one point during the investigation, an FBI agent posed as a dead man in the trunk of the informant’s car.

According to court documents and testimony, the informant asked Burgess for help in disposing of the body, and Burgess said he would do so for $250,000.

Burgess met the informant and an undercover FBI agent on July 31, 2000. During that meeting, the Review-Journal reported at the time, the two sought assurance from Burgess that he would put the body with Cary’s. Burgess said Cary’s body would be close by, but he did not disclose a location.

FBI agents decided to arrest Burgess on weapons charges, and in 2002, at the age of 64, he was sentenced to about 11 years in prison for being a convicted felon in possession of firearms and ammunition.

His defense attorney in the case, Bob Glennen, did not respond to multiple requests to comment for this story.

At this point, Smith doesn’t believe that Burgess will reveal anything.

“But you hope maybe someone else who knows something decides they want to clear their conscience,” the retired FBI agent said as he stood in the doorway of his home.

Dunn, who also testified during the trial, was disappointed by the jury’s verdict.

But, he said this month, “the most important thing at that time was not so much the conviction but getting Burgess to tell us where the body is, because that’s very important in Sol’s religion.”

In Jewish tradition, it is believed that the soul can’t start its journey back to God until the body is laid to rest, according to Rabbi Shea Harlig, director of Chabad of Southern Nevada and a friend of Sol Sayegh’s.

“The burial site is a dimension of the soul that remains, therefore when you go to a gravesite, your soul connects to the soul of the loved one,” Harlig said. “Unfortunately, they haven’t been able to do that.”

Next month, on Nov. 12, is Cary’s 47th birthday.

“It’s just so sad that it had to happen, period,” Smith said. “There was no reason for anyone to grab him except for greed.”

Contact Rio Lacanlale at rlacanlale@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0381. Follow @riolacanlale on Twitter.