Mob hit mystery? 50-year-old Las Vegas double murder baffles police, FBI

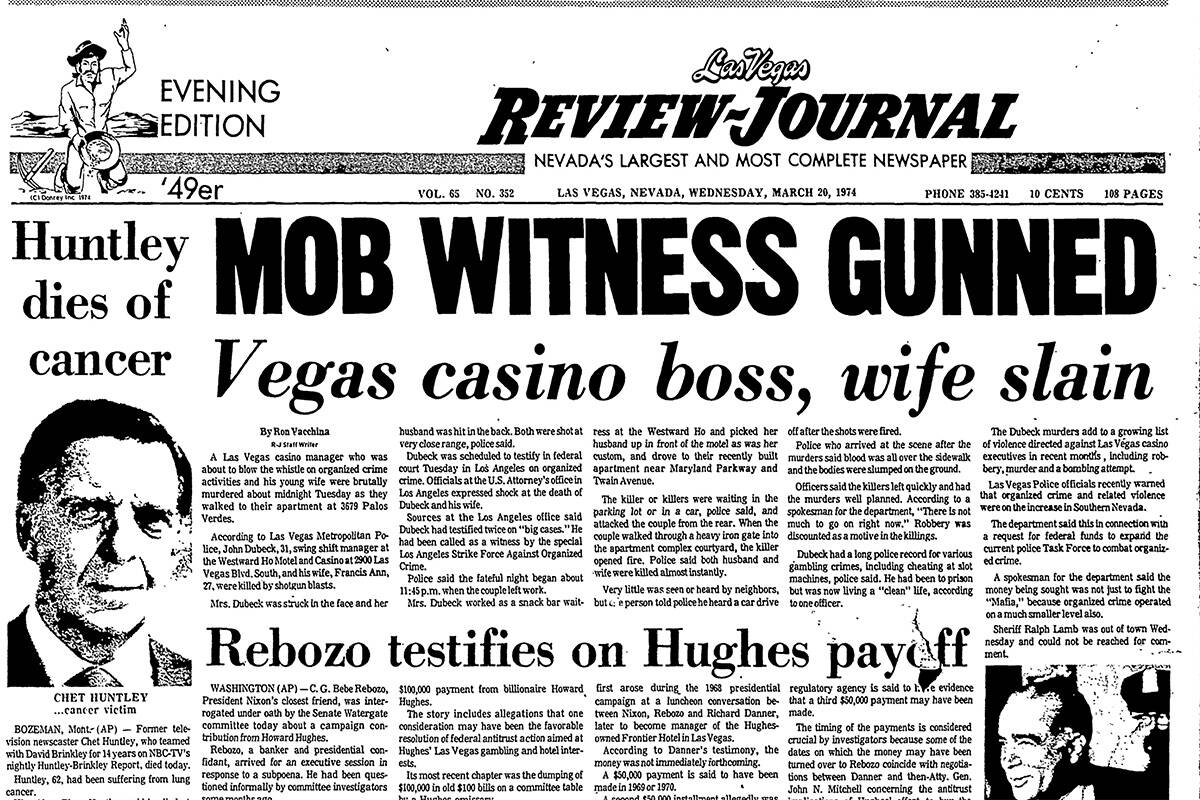

In 1974, a young couple was discovered shot to death outside their Las Vegas apartment complex. At the time, the killings left Las Vegas police, the FBI and other law enforcement officials baffled and unable to crack the case.

Fifty years later, the answers to who killed then-31-year-old John Dubeck and his wife, Francis, remain elusive and the case a mystery, despite strong past indicators of possible mob connections.

Sometime in early 1974, while 31-year-old John Dubeck worked late one night as shift manager at the Westward Ho casino on the Strip, he observed three men who appeared to be waiting for him out front.

As Dubeck would tell an FBI special agent in Los Angeles, when he arrived all three of the individuals “after staring at Dubeck for some length of time, immediately departed,” which FBI agents thought that they “may have used this opportunity…to get a look at Dubeck.”

That piece of information came from an “urgent” FBI teletype memo dated 1:45 p.m., March 20, 1974, nearly 14 hours after the bodies of Dubeck and his wife, Francis, were found outside their Las Vegas apartment complex.

The Las Vegas Review-Journal, through a Freedom of Information Act request submitted in April 2023, obtained a 50-page section of the FBI file — heavily redacted — on John Dubeck and Peter Milano, a one-time “caporegime” of the Licata organized crime family in Los Angeles who was a prime target of the federal probe into the Dubeck killings.

The identity of the person or persons responsible for the double homicide continues to baffle the FBI and the Metropolitan Police Department, which is now conducting a review of its files and evidence from the half-century-old cold case, according Lt. Jason Johansson of Metro’s homicide division.

John Dubeck, who was to testify in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles in a trial involving Milano and six other defendants — charged with running crooked Las Vegas-style casino games inside homes in the San Fernando Valley — only days before he was slain, possibly in a mob-ordered hit, said Don Fieselman, a cold case investigator for the police department.

Tough case to crack

Metro police detectives and FBI agents pursued many leads over the years, Fieselman said.

“I would say looking that case file over, they did a lengthy investigation and they never stopped doing it.” Fieselman said. “Until they retired, it seems to me they were always adding a little here and a little there.”

One of the many difficulties in cracking the old homicide case, such as the lack back then of computers linking information, DNA analysis and the widespread surveillance cameras available today, is the potential organized crime link, with suspects and associates unwilling to talk, Fieselman said.

“Whenever there is an organized crime nexus, you’ve got a bunch of suspects who aren’t going talk and their associates aren’t going to talk,” Fieselman said.

“The problem that they ran into back in the day was they didn’t have computers to link everything together so they could do reports about the case, put it in the case file and other people that might strike a chord with wouldn’t have any way to connect it,” Fieselman said.

“They did a very good job,” Fieselman said of Metro’s detectives. “They did a very extensive job. So it’s slow going to do the review, because each step they took, I have to look at it and see if they missed anything, or if I’m missing anything.”

Metro’s Dubeck case file is quite large and must be examined to be up to speed on it, including statements from many people who came forward and may have provided viable information and those who did not, Fieselman said.

“One of the things I want to do in my review is see if there are any connections that were missed back in the day because of the way we necessarily handled case files, which was with a typewriter and paper,” Fieselman said.

The file contains reports from witnesses who said they saw a car drive away after the gunshots but “some of them are just cars on the street,” he said.

The investigator said he is actually trying to find leads in two cases involving Milano that took place almost simultaneously in 1974 to check for any links.

The first is about John Dubeck, who was to testify in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles in a trial involving Milano and six other defendants — charged with running crooked Las Vegas-style casino games inside homes in the San Fernando Valley — only days before he was slain, possibly in a mob-ordered hit, Fieselman said.

The other is a heroin trafficking case against Milano out of Honolulu, where less than two weeks before the Dubeck homicide, on March 6, 1974, one of two bombs planted in a car started by one of Milano’s co-defendants failed to go off, Fieselman said.

Shooting in south-central Las Vegas

On March 19, 1974, Francis Dubeck, 27, picked up John Dubeck from work late that night at the now-closed Westward Ho, 2900 Las Vegas Blvd., South, as was her routine, Fieselman said.

At 11:55 p.m., after the couple emerged from the parking lot of their complex at 3769 Palos Verdes St. near East Twain Avenue and went through a gate, two rounds from a shotgun rang out, hitting John Dubeck in the back and his wife in the face and neck as she turned to her husband, according to Fieselman and Johansson. The Dubecks died at the scene.

There were no eyewitnesses to the killings. Some neighbors told police they heard the shots and a car speed away, although some claimed they saw a car on the street. One clue left at the scene was an empty shotgun shell, Fieselman said

On March 21, an air conditioning maintenance man located a Winchester .20 gauge pump shotgun on the roof of an apartment complex at 549 Sierra Vista Drive, near the shooting scene, and contacted police, according to Fieselman.

The long gun is the one believed used in the slayings but it can’t yet be definitively traced to it, Johansson said.

The firearm is likely still somewhere in Metro’s evidence vault, and “was probably dusted for prints,” Johansson said. “But it probably was not laid out on the sterile surface because they weren’t even thinking about DNA. They’re looking at preserving prints.”

Sports car found

Agents wrote in the FBI file that Las Vegas police detectives in 1974 speculated that the killings were performed from a moving car and the shooter drove away, according to witnesses who heard the shots and some who described a vehicle leaving the scene.

Upon the discovery of the shotgun, “an older model sports car with its hood and fenders off” was found abandoned in the parking lot outside the Sierra Vista complex, which FBI agents noted “compares somewhat with the description of the car believed to have been seen at the scene of the crime.”

Agents described Milano as an “LCN (La Cosa Nostra, or American Mafia) ‘capo’ ” in the Los Angeles organized crime group headed by Nicola “Nick” Licata.

Milano’s father Tony Milano, the FBI agents stated, “is an LCN member in Cleveland. (Peter) Milano was indicted in Los Angeles (in November 1973) based in part on testimony furnished by deceased John Dubeck,” the FBI reported.

Peter Milano visited his father in Cleveland from March 2 to March 9, 1974, days prior to the Dubecks’ deaths, according to the FBI file.

The FBI stated that John Dubeck was the “prime witness” in the U.S. government’s illegal gambling trial against defendants Milano and others indicted in 1973 and he was set to testify in Los Angeles on March 26, 1974, a week after the homicides.

The Los Angeles Times in 1974 quoted a federal agent saying that the Dubeck killings were “definitely a professional job” and done “by more than one man.”

Arrest records in Nevada

Both John and Francis Dubeck had their own cloudy pasts, with arrests records in Nevada related to gaming.

In July 1969, they were casino employees at the Sahara-Tahoe Hotel Casino in Stateline when they were arrested with a third person on suspicion of embezzling $25,000 from the casino, according to The Associated Press.

Then in January 1971, the Las Vegas Review-Journal reported that the two were arrested in Searchlight in the use of a “stringing” cheating device to force a $500 jackpot in a slot machine in Laughlin. Clark County sheriff’s deputies found three stringing devices in the couple’s car, the newspaper reported.

In mid-1971, Dubeck had been recruited to assist in operating “large scale crap games moved to various residences in San Fernando Valley” where such casino games are illegal, the FBI reported.

But it went beyond that. The government’s prosecutor in Los Angeles, Assistant U.S. Attorney James Twitty, said later in court that the casino plot with Milano and co-defendants John Vaccaro, Luigi Gelfuso, Martin Calaway and Tony Endreola used electronic equipment to “rig” casino table games, shaved or altered craps dice and marked cards for blackjack to increase profits that reached $400,000 a month, the Chicago Daily News reported.

Brazen and unheard of thing

The idea of floating casinos in suburban houses was authorized by Licate, the aging boss of the Los Angeles crime group as long as Milano made sure to give the boss 10 percent of the profits, according to the Chicago Daily News.

The scheme, involving table games moved into the living rooms of homes, lasted for several months until Los Angeles police conducted a raid on Dec. 11, 1971, the Long Beach Press-Telegram reported. John Dubeck was among those arrested in the raid.

The Chicago Daily News reported that police had been tipped off by disgruntled customers of the fixed casino games, which the paper said was “a brazen and unheard of thing in mob operations back East.”

In May 1972, Dubeck, Vaccaro and six other men — including four former Las Vegas casino dealers — faced illegal gambling charges in Los Angeles Superior Court, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Dubeck and two others facing charges, Peter Coloduros and Roman Klyatt agreed to testify for the prosecution in exchange for dropping the charges, the Chicago Daily News reported.

The FBI file mentioned that Dubeck testified before the federal grand jury that eventually indicted Milano, Vaccaro, Gelfuso, Calaway, Endreola and Manfre in November 1973.

For the trial, set for March 26, 1974, Dubeck was to take the stand and explain how the Licata crime group used prostitutes to entice customers to play the crooked games, according to the Chicago Daily News.

His death prompted prosecutors to delay the trial for several months, his place on the witness stand to be taken by Klyatt and Coloduros, the Chicago Daily News reported.

Then Richard Sherman, Milano’s attorney, felt duty-bound to report that a Los Angeles man named Frank Napoli had contacted him and offered to kill Coloduros for $25,000. Coloduros and Klyatt were put into federal protective custody while Napoli was tried and convicted in the proposed murder plot, the Chicago Daily News reported.

Dubeck rebuffed three offers of protection by federal officials, even after being told his life was in danger amid reports that two contracts were out to kill him in Las Vegas, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Twitty would say in federal court in Los Angeles after John Dubeck’s death he had evidence that Milano, Calaway, who bankrolled the casino operation, Vaccaro, who supervised the blackjack and dice games, and Gelfuso, a debt collector, all plotted to kill Dubeck and Klyatt, but the judge declined to press charges, the Chicago Daily News reported.

‘Big man in the valley’

During the trial in Los Angeles on Aug. 15, 1974, prosecution witness Robert Diamant, a Sunset Boulevard restaurant owner, testified that he had a meeting in 1971 with Calaway, Vaccaro, who was the restaurant’s manager and accountant, and Dubeck, a restaurant employee, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Vaccaro, Diamant said, proposed arranging a $50,000 loan to help Diamant’s restaurant stave off bankruptcy and then $15,000 of it would be kicked back to jumpstart a gambling operation.

Diamant said that John Dubeck told him Peter Milano “had some people who would take care of things for me” and was “a big man in the valley.”

But Diamant rejected any involvement for fear he might lost his business license, the Times reported.

The floating casino operation soon shifted to the San Fernando Valley, with Vaccaro and John Dubeck taking shares of the winnings and 85 percent going to Milano and other partners, according to the Times.

On Aug. 31, 1974, a jury found defendants Milano, Vaccaro, Calaway, Gelfuso and Endreola guilty of felony conspiring to violate gambling laws and conducting an illegal gambling business, the Times reported.

Vaccaro was convicted of separately transporting blackjack and dice games across state lines from Las Vegas.

On Oct. 21, 1974, the judge sentenced Milano, Vaccaro and the three others to four years each in federal prison.

Narcotics connection

Another possible connection to the Dubeck homicides and a narcotics deal involving Peter Milano was also investigated by federal authorities, according to Fieselman.

Milano was arrested in Los Angeles with three other suspects on Jan. 15, 1974 in an alleged conspiracy to import $7 million in heroin from Honolulu, based on a story in the Los Angeles Times.

Weeks later, in Honolulu on March 6, 1974, John Chang Ho Lee, also arrested in the suspected organized crime heroin deal, was outside the Hawaiian Hilton Hotel, entered a sports car, turned on the ignition and dynamite in the left fender blew up but a second dynamite bomb under the hood failed to work, leaving Lee uninjured, according to the Times.

Fieselman said that “it might have been as simple as Milano or one of the West coast crime crew was thought to be involved in this, and he was also involved in this gambling thing, and there was a murder.”

‘We’d all like to solve them’

Meanwhile, solving the Dubeck killings remains an uphill battle because no one witnessed any part of the shooting, Fieselman said.

“It comes down to somebody coming forward, whether it’s a deathbed confession or a letter they wrote because they want to get it off their chest that somebody finds in their grandpa’s dresser or whatever.”

Another factor in the Dubeck case is Metro has younger cold cases that have more viable leads for prosecution, Johansson said.

“And a lot of times those aren’t the ones that have the most notoriety or anything that goes along with them,” Johansson said. “So you have these old cases that are that are interesting. We’d all like to solve them.”

Contact Jeff Burbank at jburbank@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0382. Follow him @JeffBurbank2 on X.