Coroner fired investigator months after Henderson attorney’s death

Questions have surfaced in legal proceedings about the professional competency of a coroner’s investigator who concluded that attorney Susan Winters killed herself by drinking antifreeze in January 2015.

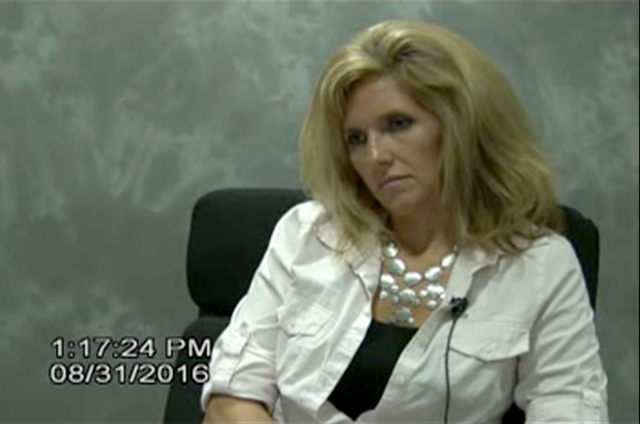

In a sworn deposition, Rhonda Borgia admitted that she had been fired months after Winters’ death because of poor job skills.

Borgia testified that her supervisors had issues with her investigative abilities, though she insisted her May 2015 termination was not related to her work on the Winters case.

After receiving Borgia’s investigative report and conducting an autopsy, a top pathologist in the coroner’s office concluded that the cause of Winters’ death was her consumption of a lethal combination of prescription painkillers and antifreeze at the Henderson home she shared with her husband and their two daughters.

The pathologist, Alana Olson, said the manner of death was a suicide.

But authorities now suspect that Winters, 48, met with foul play at the hands of her husband, longtime Boulder City psychologist Gregory “Brent” Dennis, who was informed in August that he was the target of a grand jury homicide investigation.

In her Aug. 31 deposition, taken as part of a lawsuit brought against Dennis by the Winters family, Borgia had trouble explaining the difference between cause and manner of death — one of the basic concepts of the coroner’s office.

“Do you understand what the definition of cause of death is?” Winters family attorney Anthony Sgro asked Borgia during her deposition.

“I know the difference between cause and manner,” Borgia responded.

“Tell me what the difference is,” Sgro said.

“One is how the person died and — and how that person died,” Borgia stated.

“I think you just said the same thing,” Sgro retorted.

Borgia then tried to explain the difference, but Sgro pressed her further for a definition of cause of death, prompting Borgia to reply, “I don’t recall the definition of that right now.”

“You worked as a coroner investigator for three years, correct?” Sgro asked.

“Yes, approximately,” Borgia responded.

“Cause of death and manner of death are pretty much terms of art you use every day, aren’t they?” the attorney asked.

“They were.”

“And a year or so since your departure from the coroner’s office, you’re unable to articulate today the definition of cause of death?”

“I am.”

Sgro asked Borgia to explain what led to her dismissal.

“There were issues that were of concern from my supervisor’s standpoint that were presented to me,” Borgia testified.

“And those issues being the quality of your forensic work?” Sgro asked.

“My performance as an investigator, yes,” responded Borgia, who admitted that the issues had been raised by her supervisors before she was assigned to the Winters case.

But when Sgro asked Borgia whether she thought she had done a “good job” on the Winters case, Borgia said yes.

Clark County Coroner John Fudenberg shared that opinion in a recent interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

“I don’t have any concerns with her investigation as it relates to this case,” he said.

Fudenberg would not say why Borgia left his office, calling it a private personnel matter.

He did, however, confirm that Borgia began working full time as an investigator in July 2014, five months before she was assigned to the Winters case.

She was hired in October 2012 as a part-time investigator earning $15 an hour and was put through normal investigative training in the office, Fudenberg said.

New investigators attend seminars at the office’s reserve investigator academy, undergo field training, learn about critical lab work and observe autopsies, according to Fudenberg.

He said the educational process lasts from two to five months, depending on the background of the applicant.

At the moment, Fudenberg said, the coroner’s office has 16 full-time and 12 part-time investigators.

Borgia did not return phone calls for comment last week.

She admitted in her August deposition that she had little experience for the job other than managing a medical office and serving as a certified respiratory therapist at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center. After leaving the coroner’s office, she took a job as a receptionist at a private charter school, she testified.

TWO-HOUR INVESTIGATION

In her investigative report and under questioning from Sgro during her deposition, Borgia said her conclusions about Winters’ death were primarily based on information provided by Dennis, who insisted that his wife had killed herself.

Borgia acknowledged under oath that she did little to challenge Dennis’ assertions and overall spent less than two hours investigating Winters’ death, mostly at the hospital and at the family’s home. Winters died Jan. 3, 2015.

In September, a Review-Journal story raised questions about whether Winters had killed herself. The story reported that the Clark County district attorney’s office had served Dennis with a Marcum notice, indicating it was going to present evidence against him before the grand jury investigating his wife’s death.

Since publication of the Review-Journal story, Henderson police have acknowledged that they reopened their investigation.

Police spokeswoman Michelle French said last week that she had no updates on the investigation.

Fudenberg declined to discuss whether his office has received additional information from police. He previously has said he would consider new evidence.

The reopened police investigation is the result of efforts by Avis and Danny Winters, the parents of the deceased. They refused to believe that their daughter took her own life. The Oklahoma couple, who became wealthy running Sonic hamburger franchises, hired Sgro and his partner David Roger to file the lawsuit against their daughter’s husband.

It alleges Winters died under “suspicious circumstances,” and it blames her demise on Dennis, 54, who it contends had a financial motive. It also alleges that the original Henderson police investigation into her death was inadequate. The lawsuit has been put on hold amid the new homicide investigation.

Roger, who served as Clark County district attorney for a decade, prepared a 49-page report with the help of a retired FBI agent. It delves further into suspicious circumstances surrounding Winters’ death and the alleged motives of her husband. The report, which was examined by the Review-Journal, was given to the district attorney’s office and Henderson police.

Dennis’ attorneys, David Chesnoff and Richard Schonfeld, have denied that he had anything to do with his wife’s death.

Chad Mitchell, a former Henderson detective, testified in his own deposition in the civil case that he relied in part on Borgia’s interview with one of the couple’s daughters in deciding to wrap up his original investigation on Feb. 19, 2015. He said the interview had corroborated Dennis’ contention that Winters was suicidal.

But when presented with some of the circumstantial evidence collected by the attorneys for the Winters family, Mitchell started to question his decision to close the case.

Mitchell, now a patrol officer for Henderson police, said he was unaware that, just days after the death, Dennis cashed a $180,000 check drawn from his wife’s bank account.

The detective also did not collect Dennis’ phone records around the time of his wife’s death. Lawyers for her parents reported that Dennis had made several phone calls, including some to his drug dealer the morning she died. Had he been aware of the calls, Mitchell said, he would not have closed his investigation.

“I’d have some questions as to why those weren’t told to me,” Mitchell said. “And I’d want to know who they were to and why those phone calls were being made at that time frame especially. … So it would have definitely piqued my interest as to why he’s making additional phone calls when his wife is lying dying next to him.”

Mitchell said he also was not aware at the time about Dennis’ now-admitted drug use.

DETECTIVE: NO PROBABLE CAUSE

Still, when questioned further by Schonfeld, Mitchell was hesitant to conclude that Winters had been killed.

“As you sit here, you’re still not convinced that this was a murder, correct?” Schonfeld asked during the Aug. 30 deposition.

“I’m convinced that it needs definitely some further investigation,” Mitchell replied. “But none of what I heard today proves murder.”

“Right,” Schonfeld said. “And none of what you heard today would give you probable cause with which to charge Mr. Dennis with murder, correct?”

Mitchell responded, “Correct.”

He said Dennis had been drinking and his behavior appeared erratic, but that also did not give police enough reason to pursue charges.

According to his testimony, Mitchell met with Borgia at St. Rose Dominican Hospital, Siena campus, and the two examined Winters’ body together.

“There was nothing really outwardly about the body that screamed foul play,” Mitchell said.

But in her deposition, Borgia acknowledged that she never had seen a case in her short career as a coroner’s investigator in which someone had drunk antifreeze.

“Did it not strike you as odd that this decedent had supposedly ingested antifreeze?” Sgro asked.

“No,” Borgia responded.

“There was nothing … no light that went off, no switch that clicked in terms of how this woman was poisoned supposedly with antifreeze?” the attorney asked.

“No,” she replied.

Borgia acknowledged, however, that she might have changed her opinion that Winters killed herself had she known about the evidence uncovered by her family.

“If the totality of what I’m beginning to represent to you is true, does it look like this is the kind of case that probably needed more than two hours … worth of your time?” Sgro asked.

“Yes,” Borgia replied.

Contact Jeff German at jgerman@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4564. Follow @JGermanRJ on Twitter. Contact David Ferrara at dferrara@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-1039. Follow @randompoker on Twitter.