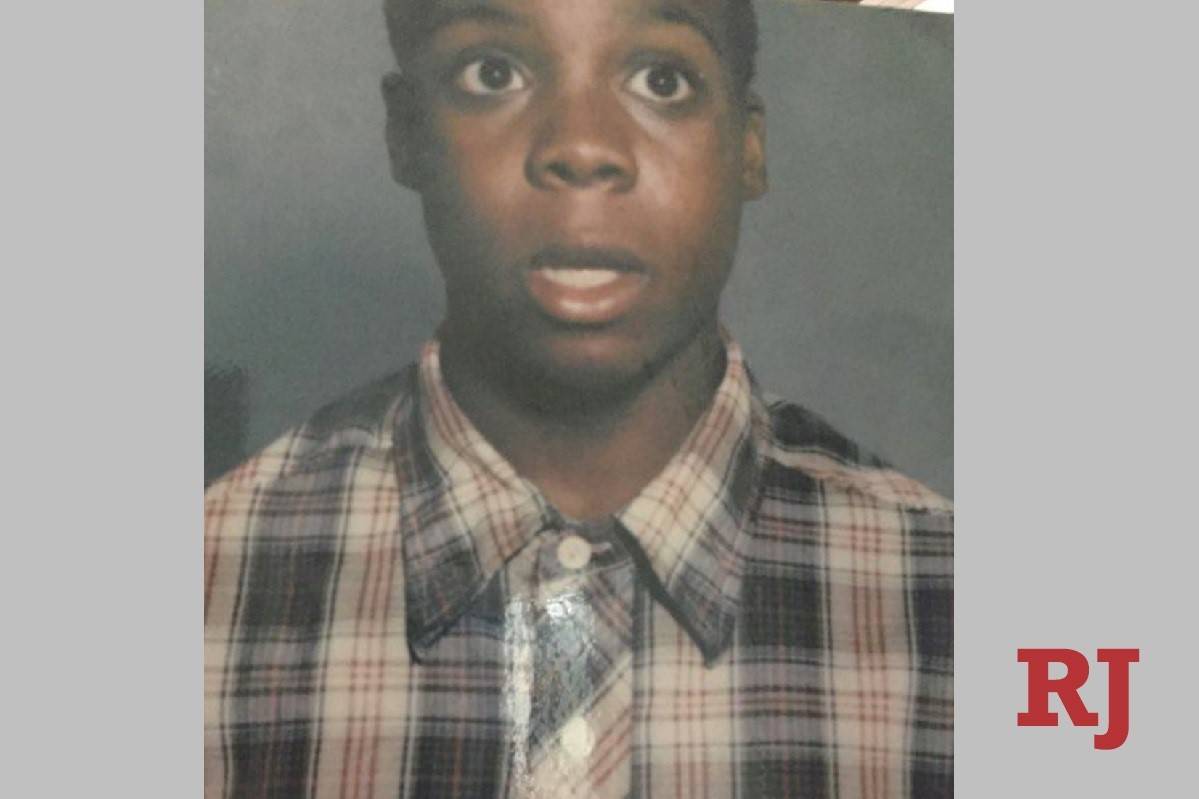

Wrongly convicted as a teen, it took decades to win his innocence.

Reginald Hayes had spent nearly half of his life in prison for a murder he did not commit by the time he was freed from custody in 1998.

Clark County prosecutors have never accused Hayes, born Reginald Mason, of any involvement in the 1985 killing that landed him in prison for 13 years, three months and 11 days. Instead, they argued that the 14-year-old middle school student with no criminal record was guilty under Nevada’s felony murder law because he was present at the time of the victim’s kidnapping, which led to the slaying.

“It was a tragedy that he was even convicted, let alone in prison for all these years,” then-Las Vegas police Undersheriff Richard Winget wrote in a letter of support to the judge who ultimately granted Hayes freedom after years of appeals.

A year after his release, the state Board of Pardons unanimously pardoned Hayes based on his innocence. But more than two decades would pass before the Las Vegas man was granted the highest form of criminal record expungement: a certificate of innocence, awarded this week by the state along with $975,000 in compensation.

“I am elated that after many years, Mr. Mason has been declared an innocent man after he was arrested and convicted as a teenager. Time was stolen from him at a young age and no one can replace that,” Attorney General Aaron Ford said in a statement Thursday. “The pursuit of justice is paramount to the mission of my office and I could not be prouder of the attorneys in my office who worked on this case to obtain justice for Mr. Mason.”

Growing up in a cage

Through his lawyer, Franny Forsman, Hayes declined to speak for this story. But on Friday, Forsman told the Las Vegas Review-Journal that Hayes, now 50, turned out to be “a really, really solid guy for somebody who grew up in a cage.”

“The award is not enough to make up for the most important years of his life spent in a cage,” she added. “But it’s a little bit of justice.”

Forsman has known Hayes since he was 15 — “longer than I’ve known one of my own kids,” she said Friday.

The longtime defense attorney represented Hayes through all the stages of his appeals, his release, the pardon and, finally, his certificate of innocence, which marks the “very last case” of her decadeslong career.

“It was an honor,” she said of her work in seeking justice for Hayes.

Looking back on the case, Forsman said, “It took a long time, knocking on a lot of court doors, to get someone to listen to us.”

“The real breakthrough came when the undersheriff, Richard Winget, spoke up,” Forsman recalled.

In addition to Winget’s letter, other letters of support were written by family members, community leaders and even the two detectives who arrested Hayes on the night of the shooting.

“This young man has spent half of his life in prison because he was in fear of what might happen to him if he didn’t stay,” one of the detectives wrote. “I’m just glad that when I was 14 years old, I didn’t have to make that type of decision. I may have gone to prison instead of becoming a police officer.”

‘A tragedy of errors’

On Aug. 10, 1985, Hayes accepted a ride home from a group of older teenagers that changed his life. The others in the car were Philip Minor, 18, and Eddie Hampton and Donald Lee, both 16.

Instead of taking Hayes home, according to a 1999 Review-Journal story, Lee took a detour and, at gunpoint, kidnapped John Brown, a 21-year-old Nellis Air Force Base airman. Authorities have said Lee and Minor beat Brown in an alley and robbed him of $9 before fatally shooting him.

At trial, the four defendants also were accused of shooting out the car window earlier that day, trying to kill four other people.

Hayes’ trial attorneys argued that he was not inside the car during the earlier shootings and was merely present, helpless and terrified during the kidnapping that led to Brown’s death.

In 1999, about a year after his release, he told the Review-Journal: “I’ve learned to channel my anger and frustration with the justice system. Now I understand it’s sometimes not about justice, it’s about dollars.”

At the time, he said he didn’t blame the jury that convicted him, nor did he harbor any hard feelings for his co-defendants.

But he did find fault with other key participants in his trial:

— His attorneys, who had provided ineffective counsel.

— The prosecutors, who, Hayes said, were more interested in winning than properly evaluating the roles each of the defendants played.

— And the presiding judge, Paul Goldman, who less than a year after the trial resigned in light of an “emergency investigation” of judicial misconduct by the Nevada Supreme Court. The investigation later revealed “willful misconduct” by Goldman that began about a year before Hayes’ trial.

“It was a tragedy of errors,” Forsman, Hayes’ attorney, said Friday.

Today, Hayes works as a foreman on a construction crew in Las Vegas. And with his compensation from the state, Forsman said, her client hopes to soon pursue a college degree — maybe in communications.

“He’s a pretty remarkable fellow. He’s so responsible,” Forsman said. “I really want people to know that.”

Contact Rio Lacanlale at rlacanlale@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0381. Follow @riolacanlale on Twitter.