Nevada Cancer Institute facing lawsuit

The commitment to compassionate care for cancer patients is on the Nevada Cancer Institute’s website for all the world to see: Giving "support and hope" to them is "first priority."

Whether that assertion by the institute is true — at least as it applies to one of the nonprofit’s top administrators who is battling cancer — is now open to question as a result of a lawsuit filed against the institute in state District Court.

It turns out that as the financially troubled institute shed jobs last month as it tried to manage $100 million in debt, cancer patient Meredith Mullins, then the institute’s senior vice president of research operations and associate center director of research administration, was one of the more than 150 researchers, doctors, nurses and administrative staff who were fired.

The institute’s senior management team, according to the lawsuit filed by Mullins, "were aware that plaintiff (Mullins) suffered from cancer … aware that plaintiff was on medical leave … aware that plaintiff needed medical insurance to cover her cancer treatment."

"I didn’t want to file a lawsuit," Mullins said Friday. She said she told top officials within human resources that she would be more than willing to take much less salary to keep the insurance that she was using to pay for thyroid cancer treatment.

The answer, she said, was no.

She said she then had an attorney write a "nice letter" requesting more time on the payroll so she could keep the insurance she had for herself and her fiance, Martyn Bouskila, an artist who is undergoing treatment for cardiovascular problems.

"When we received no answer, I felt I had no alternative but to file a lawsuit," said Mullins, who began working at the institute in 2009. With overseeing contracts and winning grants for the institution, she was in charge of laying the foundation for the institute becoming one of National Cancer Institute’s Centers of Excellence,

That designation, held by only 63 centers in the nation, would mean the institute could use a greater variety of treatment regimens.

"I love helping startup institutions get that (designation)," said Mullins, who worked with cancer centers in Florida and Oregon that earned the prestigious classification.

Mullins’ litigation, which asks the court for special damages more than $10,000 as well as compensatory and punitive damages to be proven at trial, said her employment agreement provided for her to receive "one year notice prior to any termination" and "severance pay for one year."

Hilarie Grey, a spokeswoman for the institute, said she could not comment on pending court matters.

Mullins’ April 26 lawsuit, prepared by attorney Daniel Marks, was the second filed in the wake of the April 8 layoffs at the institute.

An earlier lawsuit filed in federal court by former clinical research coordinator Shamine Poynor, which seeks class-action status, argues that she and all of the more than 150 employees who were laid off on April 8 should recover 60 days of wages and benefits.

That lawsuit said the federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act of 1988 requires employers to provide a 60-day notice before a mass layoff. Companies that do not follow the law can be ordered to pay former employees back pay and benefits for two months.

Dr. John Ruckdeschel, the former director and CEO of the institute who was fired a week before the mass layoffs, confirmed that senior management was aware of Mullins’ cancer fight. "It was not an easy time for her," he said.

Mullins, 45, said she learned she had thyroid cancer in February. With surgery pending in March, she said she signed up for the Family and Medical Leave Act, which allows employees with serious health conditions to take up to 12 work weeks off during a year. The act allows employees to work part time and gives them the right to return to the same or equivalent position, pay and benefits at the conclusion of their leave.

Unfortunately, Mullins said, she had to go out of town for surgery after she concluded that local surgeons weren’t familiar enough with the surgical intervention she needed. So she went to UCLA’s medical center in Los Angeles, where she had a total thyroidectomy, an operation that involves the removal of the diseased thyroid gland.

Heather Murren, a co-founder of the institute, has said a major reason for starting the research and treatment institution in Summerlin was to ensure that cancer patients wouldn’t have to leave town.

The institute hospital that Ruckdeschel said was necessary to help make the institute financially viable has never materialized, and he now believes it never will.

Shortly after her March operation, Mullins said she received calls from the institute.

"Within eight hours of rolling off the operating table, I was receiving calls asking me to further reduce my personnel budget," she said. "I asked them if I could please have some time (to recuperate)."

Mullins said she was well-aware that the institute was having financial problems.

"We had just had some other layoffs prior to my operation," she said.

In March, the institute’s board fired 30 support staffers, blaming the economic downturn for hurting fundraising.

Hoping to help the board through its fiscal challenges and desiring to make a reality out of Murren’s dream of developing the institute into one of the National Cancer Institute’s Centers of Excellence, Mullins said she started working more part-time hours than her doctors preferred.

"They told me to slow down," she said.

On April 8, she said she received a phone call from human resources telling her that the clinical trials office would be downsized, and she might be one of those who could be terminated.

She told the caller that she thought she was protected by the Family and Medical Leave Act and said if she were going to be fired, she wanted to know immediately.

She said she was not told she was fired then and continued to work part-time through April 13, when she was notified through a phone call.

Mullins said she thinks a financial consultant hired by the institute to keep it solvent was responsible for her firing,

"I think he saw my cancer treatment as an expensive liability and argued that they should get rid of me," she said. The consultant, she said, was paid $600,000 "upfront" by the board to advise them on financial matters.

Mullins, who earned more than $200,000 a year at the institute, is using money from her retirement to pay her mortgage, day-to-day bills and the $800 a month to keep her health insurance active under the federal COBRA act. Her fiance, an artist whom she is marrying in Arizona on June 5, is now without health insurance.

"I’m doing everything I can right now to land another job somewhere," she said. She does not believe her cancer will be held against her.

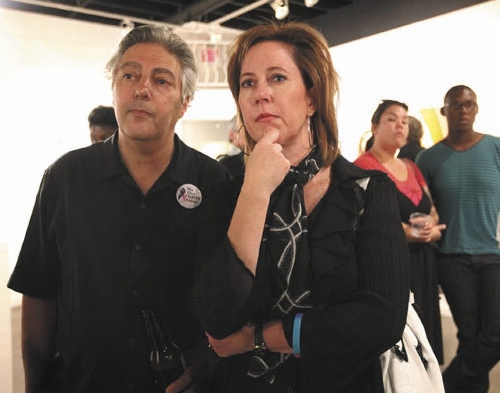

On Thursday night, Mullins, who holds a master’s degree in business on top of a bachelor’s in biology, was trying to be upbeat as her fiance exhibited artwork at the Arts Factory on Charleston Boulevard. In a week, Mullins will have something else to be upbeat about: She will graduate from University of Detroit Mercy School of Law. (After moving to Las Vegas, she completed some studies at UNLV’s Boyd School of Law.)

But the stress from her situation at the institute, Mullins said, has taken its toll, with doctors saying it has compromised her immune system.

"My doctors tell me I can’t have my radiation treatment now until later this summer," she said. "My prognosis is supposed to be good once I get that over with."

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@review journal.com or 702-387-2908.