An old idea gains traction with Las Vegas Strip train tunnel proposal

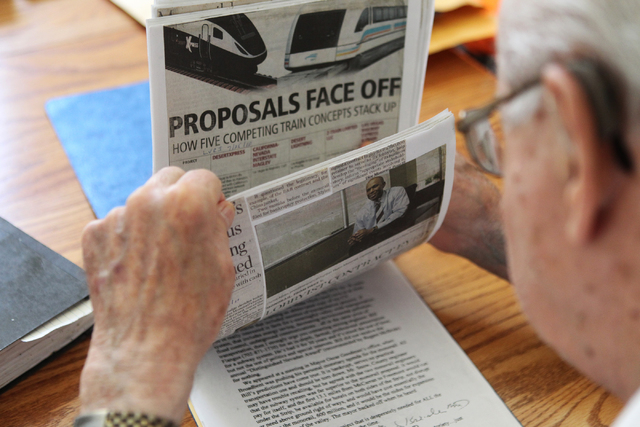

When historians look back at the achievements of Las Vegas resident William “Bill” Flangas, they may end up remembering him most for a tunnel project he pitched but never got to see built.

Flangas proposed an underground train from McCarran International Airport and along the Strip — in 1974.

In light of last week’s unveiling of the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada’s Transportation Investment Business Plan, which includes an underground light-rail system beneath the Strip, this makes Flangas about 41 years ahead of his time.

Flangas, who was graduated from the University of Nevada, Reno with a degree in metallurgical engineering in 1951, worked for Kennecott Copper in South America and in Ruth before enjoying a 37-year career at the former Nevada Test Site.

He eventually became manager and vice president with Reynolds Electric and Engineering, the general contractor of the Nevada Test Site, now known as the Nevada National Security Site.

But some of his best days were from 1958 to 1979, when Flangas was tunnel superintendent and manager for the team that moved atmospheric nuclear weapons testing underground.

Flangas oversaw the excavation of seven major tunnel complexes, including a 12-foot-diameter vertical “big hole” for nuclear testing. By the time his work was done, he had overseen the drilling of 47 miles of tunnels.

He also was part of the first underground recovery team entering a ground zero zone after an atomic blast and once miraculously escaped serious injury when a hydrogen gas pocket explosion hurled him several hundred feet.

Aboveground, he was on monitoring teams for the Threshold Test Ban Treaty and the Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty and was involved in Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty efforts.

When in Moscow on a monitoring trip, Flangas saw the city’s extensive subway tunnels, inspiring an idea that would serve him in his post-Test Site life:

Why not tunnel under McCarran and run a line along the Strip?

MOSCOW IN THE DESERT

Flangas has the original copy of an eight-page proposal given to the Clark County Commission on Aug. 5, 1974.

He envisioned an 11.2-mile system from the airport to downtown, with vehicles 11 feet wide and 10 feet tall on dual tracks 150 to 200 feet below ground-level. A pipeline at the bottom of the tunnel would provide both drainage and a conduit for utilities.

He suggested that the government be responsible for the main transportation line, but resorts along the line pay to access the system, including construction of their own stations.

The Strip corridor eventually would be the core line for a system that would branch out across the valley, much as the Moscow subway has a Moscow circular route with intersecting points. His objective was to have routes to Henderson, the Summerlin area, northwest Las Vegas, North Las Vegas and the east side of the valley, all connecting to the central core.

Then-Gov. Mike O’Callaghan embraced the concept, writing about it years later as executive editor of the Las Vegas Sun when the proposal resurfaced when the Regional Transportation Commission was debating construction of a monorail system. But decision-makers at the time argued the cost of going underground was too great, and the monorail proposal, spearheaded by former Clark County Aviation Director Robert Broadbent, won out as the preferred project.

Flangas argued that an underground system would be shielded from the intense summer heat and would be more durable than a monorail. Resort officials didn’t like the idea of a center-Strip monorail because they felt the tracks would detract from iconic resort themes.

Although Flangas penciled out costs equal to or less than the monorail, the proposal was scuttled as too expensive.

The monorail along the rear entrances to properties on the east side of the Strip was built with the promise that it would be extended to the airport, and a second line would serve the west side of the Strip. But as ridership waned, the Las Vegas Monorail Co. drifted into bankruptcy without ever being extended.

Flangas, who turns 88 today, is in declining health, with some short-term memory loss; but he remembers most of the details of the system he designed. He and his wife, Marilyn, a former White Pine County beauty queen who also worked for Kennecott, live in Summerlin.

Flangas kept meticulous notes on the project as well as newspaper clippings about his proposal and about the monorail that defeated it. He has thousands of pages of documents and notes, neatly preserved in binders.

MOVING MANY TOURISTS

What may be the most striking aspect of Flangas’ tunnel plan is how closely it resembles what was rolled out last week by CH2M, the Transportation Commission’s transit consultant.

David Knowles, senior transit planner and vice president for CH2M in Portland, Ore., doesn’t believe his colleagues have reviewed any of Flangas’ proposals.

“We have our own tunnel expert who was a part of our team that drafted the proposal, and the group came to the conclusion that an underground light-rail system would be a viable solution to the challenge,” Knowles said.

While the consultants haven’t conducted any boring tests, the company’s tunneling expert believes the geology would be suitable for the system envisioned.

The commission is eyeing a plan that would transport the high demand of tourists through the most congested parts of the Las Vegas Valley. Local proponents who developed the plan want to move large volumes of people in vehicles that would enhance the visitor experience.

Most urban transit systems focus on commuters, but the prime users of the Las Vegas system would be tourists. Knowles also explained that the Las Vegas system is envisioned as underground light rail, not a traditional subway.

Light-rail systems have an overhead power system and can operate below grade, on street surfaces and on elevated tracks. Subways draw power from an electrified third rail and tend to be bigger and louder.

Like Flangas, Knowles and his team see little challenge in boring through any surface, including caliche, a cement-like sedimentary rock common in Southern Nevada. Flangas considers caliche a plus because hard tunnel walls would be easier to shore up as a boring machine cuts through.

Although Knowles and his group haven’t met Flangas, they consider his 40-year-old plan an assurance that they are on the right track.

As for Flangas, he is happy to see his idea come up again.

“It is never too late to start doing the right thing,” he said.

Follow @RickVelotta on Twitter. Contact reporter Richard N. Velotta at rvelotta@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3893.