Former Las Vegas developer’s big project ideas still going nowhere

BEE CAVE, Texas — Chris Milam once said he is different from most developers.

He wants a fair profit, not an excessive one, and is driven “more by a desire for the greater good,” he wrote in an email to a Bee Cave councilman nearly three years ago.

Milam’s group later sued Bee Cave leaders, and his real estate proposals ended the same way as his big projects some 1,300 miles away in Southern Nevada: He never built them.

Developers are building projects throughout the Las Vegas Valley, including several that cost a billion dollars or more. But as construction booms, the region’s history of real estate flops should not be forgotten.

Southern Nevada, despite boasting plenty of massive projects that are up and running, also has a lengthy track record of developers pitching big ideas and never following through. And in the not-too-distant past, Milam was prolific at it.

He spent years pursuing billions of dollars worth of projects in the Las Vegas area before and after the economy tanked with nothing to show for them. His last plan in the valley — a four-venue professional sports complex south of the M Resort — ended in 2013 with the city of Henderson suing him, and Milam agreeing as part of a settlement to never again do business in the city.

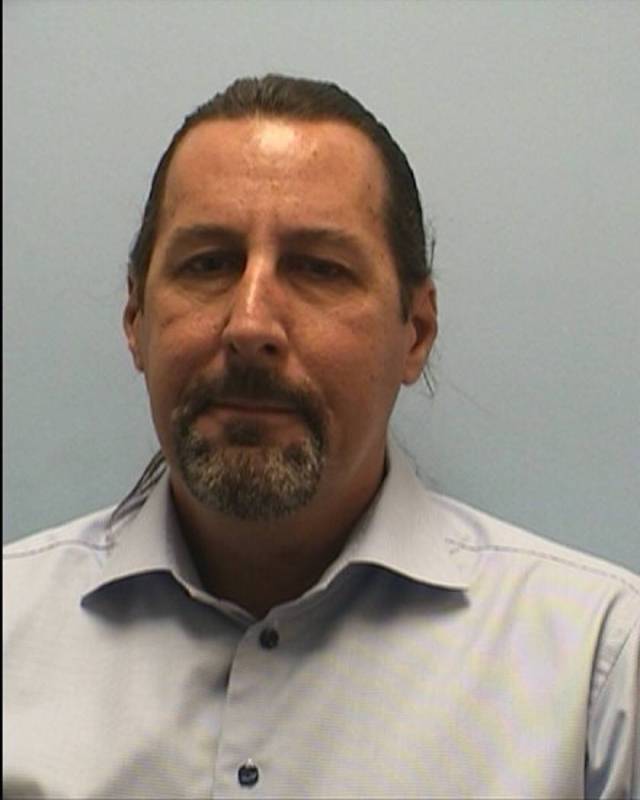

In written responses to questions for this story, the 58-year-old developer told the Las Vegas Review-Journal he loves Las Vegas, he “took quite a lot of abuse” over his multivenue sports proposal because people thought he wasn’t realistic, and he hasn’t been to Southern Nevada for years.

He also said his years in the valley were “difficult for all of us. But we tried.”

After his time in Las Vegas, Milam headed back to the Austin, Texas, area and followed a familiar arc: He partnered with a wealthy business figure and made big projections but never built his projects.

“He’s a very good salesman,” Bee Cave Mayor Bill Goodwin told the Review-Journal last year.

Unlike other developers, Milam was a “serial” promoter, said RCG Economics founder John Restrepo, who did a fiscal benefits analysis for Milam’s Henderson project.

Typically, he said, developers might pitch project plans a few times but move on if they flame out.

Big plans

Milam surfaced in Las Vegas after Hard Rock Hotel developer Peter Morton announced plans in 2004 for a $1 billion hotel-condo project next to the off-Strip resort. Milam was involved with the project by spring 2005, appearing with Morton at a media event, but their business relationship eventually fell apart, according to court records.

Morton shelved the expansion and sold the Hard Rock and other assets for $770 million in cash in 2006. He could not be reached for comment.

Amid the bloated real estate bubble, Milam reached a deal in 2006 to buy the 27-acre former Wet ’n’ Wild water park site on the north Strip for $450 million and filed plans for a monster skyscraper: a 142-story casino-resort.

Australian billionaire James Packer later teamed with Milam and a New York investment firm to develop Crown Las Vegas at the Wet ’n’ Wild site. But by mid-2008, with the economy stumbling, they bailed on the $5 billion high-rise project.

Packer’s company Crown Resorts did not respond to an inquiry from the Review-Journal seeking comment from Packer.

In 2010, after the market had crashed, Milam filed plans for the 20,000-seat Silver State Arena at the same property. The $750 million project would “light this area on fire” with economic activity, he said at the time.

That, too, wasn’t built.

With the economy still spiraling in early 2011, Milam proposed building Las Vegas National Sports Center, a downtown complex with an arena and two stadiums that would reportedly cost nearly $1.6 billion. By spring 2011 he wanted the project – then slated to cost almost $2 billion – at the current Allegiant Stadium site west of the Strip.

But he soon changed the location again, drawing up plans for an arena and three stadiums in the Henderson desert.

‘Best interests of the city’

Milam told the Henderson City Council he had the rights to the next Major League Soccer expansion franchise; was in discussions with several NBA team owners; held talks with billionaire tech mogul Larry Ellison; and could guarantee 200 events per year even if he couldn’t land a pro basketball team, according to the city of Henderson’s lawsuit against him.

He also told council members his sales staff was generating new business every day, his financing was “fully approved,” and there was a key difference between him and his competitors.

“The rest of them don’t have the best interests of the city of Henderson in mind,” Milam said. “We do.”

Milam bought the project site, some 480 acres of federal land, in mid-2012 with a $10.5 million bid to the Bureau of Land Management. But months later, the same day the balance of the purchase was wired into escrow, he hand-delivered a letter to the city terminating the project plans, saying they were no longer viable, according to court records.

The city sued Milam and others involved in the project in early 2013, claiming they made “numerous false and misleading” statements to city officials, and “conspired” to acquire public land at a discount and sell it in pieces to developers “at a substantial profit.”

Milam settled the lawsuit within a few months. According to a federal report, he agreed to pay the city $4.5 million, to have his investors replace him in the land sale process, and to never do business in Henderson again.

After the case settled, M Resort developer Anthony Marnell III told the Review-Journal that Milam “bit off more than he could chew” and “has a track record of more proposed and not-built projects than anybody who has ever come to Las Vegas.”

Former Henderson City Attorney Josh Reid, who took his post after Milam reached a development agreement with the city, said a few months ago that the situation with the developer was a product of the recession.

With the economy limping along, officials were “a little too overeager” to land a big project, causing them to not scrutinize the proposal close enough, he said.

“Hopefully people remember the lessons there,” Reid said.

‘World class’

Several months later, in fall 2013, Milam was in Bee Cave pitching plans for a film studio, saying it was “intended for major Hollywood productions,” according to a news report.

He was no stranger to the area. His company, International Development Management, was based in Austin, and Bee Cave officials said he had developed two big retail projects in their city, some 15 miles west of the Texas Capitol: Hill Country Galleria and Shops at the Galleria.

“He had some credibility here,” Bee Cave City Manager Clint Garza told the Review-Journal last year.

Milam set out to build a 35-acre project with sound stages, office buildings, a hotel and more at The Backyard, a shuttered music venue in Bee Cave. He later scrapped the film-production space and added data centers and a power plant to the project, city records show.

He also drew up plans for The Terrace, a 19.5-acre project nearby that was supposed to feature condos and offices.

The Backyard was projected to cost more than $358 million, and The Terrace was estimated at nearly $203 million, records show.

Milam, who said the proposals were part of the same project, teamed with Texas billionaire John Paul DeJoria, co-founder of Patrón tequila and John Paul Mitchell Systems hair products, and held a ceremonial groundbreaking in 2017.

Ultimately, the most construction at The Backyard while Milam was still involved with the project was the unauthorized removal of trees, Lindsey Oskoui, Bee Cave’s director of planning and development, told the Review-Journal last year.

Milam indicated that only “underbrush for fire control and surveying” was removed. The subcontractor cleared more than the permit allowed and was replaced, he added.

DeJoria, whom Milam called “the owner” in the venture, could not be reached for comment for this story.

$50 million lawsuit

Milam talked up his efforts to Bee Cave officials, as seen in emails obtained by the Review-Journal in a public records request.

In mid-2016, he sent financial records to then-City Manager Travis Askey and cited the “huge ongoing monthly expenditures on world class architecture and engineering.” In early 2017, he told officials that The Backyard would be “the foundation of a significant evolution” in Austin’s fine arts community.

However, legal troubles soon surfaced. In summer 2017, an energy company that expected to provide utility services for the project sued Milam, claiming, in part, it was cut out of the deal before it received “any reasonable compensation.”

They settled the case, court records show.

In early 2018, Milam’s Backyard Partners entity sued then-mayor pro tem Goodwin and two Bee Cave council members, seeking more than $50 million if the city did “not allow” the project to move ahead as planned.

The lawsuit, which claimed the city leaders “actively campaigned to prevent” the redevelopment of The Backyard site, was reportedly dropped last year.

“I’m just gonna be blunt: If there hadn’t been a $50 million lawsuit, and there hadn’t been this guy, it wouldn’t have been as high-profile,” said Garza, who took the city manager’s post after the suit was filed.

Last year, a representative for The Backyard confirmed that Milam was no longer involved in the project.

Milam said he doesn’t know whether he will build another project, though he will not try something in Southern Nevada again, adding he “of course” doesn’t “feel good” about how the arena-and-stadiums project ended.

“It was jarring that I could spend so much time, energy and capital attempting to do something beautiful and positive for the community at a very difficult time,” he said, and “ultimately be painted in such a negative light.”

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342. Follow @eli_segall on Twitter.