William G. Bennett

In a town famous for giving people second chances, nobody made more of that chance than Bill Bennett did. Bennett went broke trying to be a financial player. It wasn’t his fault, said Bennett, but “I was so damned embarrassed I wanted to get out of town.” So he moved to a new city and a new industry, and became arguably the most successful gaming executive of the 1960s and 1970s.

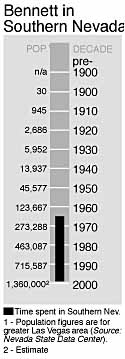

Bennett and his partner, Bill Pennington, took over Circus Circus when it was bleeding red ink, and turned it into a money machine. They showed Las Vegas how to cater to a middle-American family market, establishing the trend which dominated the casino industry for two decades. The company they took public started Wall Street’s love affair with casino stocks. They diversified the company’s operations into other cities, yet Bennett also pressed the industry to nurture its own town and talent.

In his 70s, when younger executives pushed him out, Bennett promptly bought an ailing casino and started rebuilding it.

Becoming a gambler wasn’t in his life plan. Son of an Arizona rancher, he was born Nov. 16, 1924, and served in the Navy as a dive-bomber pilot during World War II. He came home to build a chain of furniture stores headquartered in Phoenix, then sold out in 1962 and concentrated on investments.

“A friend of mine started a financial corporation. Every other company the guy ever started made a lot of money.” When stock didn’t sell as well as expected, Bennett, believing in the company, snapped up all he could get. “I got to be kind of a pig,” he admitted ruefully. Mismanagement by a company official led to public scandal and the stock dropped $20 in a single day, and eventually dropped to $2. “It bankrupted me,” said Bennett.

Bennett was acquainted with L.C. Jacobsen, president of the Phoenix-based Del Webb Corp., a construction and land-development company that had diversified, at Jacobsen’s urging, into casino resorts. “He had been wanting to get nongambling types into the business,” explained Bennett in a 1975 interview. “Most of the people running the hotels at that time had come up through the ranks as dealers, shills and so forth, and they really had no business background at all.

“Jacobsen’s idea was to get people with business backgrounds and business educations, and teach them the gambling business really fast. At that time it was a pretty revolutionary idea, and I’m the only one who was ever accorded the privilege by the Webb corporation — Jacobsen’s reign as president ended soon after that.”

He began in 1965 at Del Webb’s Sahara Tahoe, where he worked as a casino host at night and spent his days working in the hotel’s departments, one by one, until he thought he understood them all. In six months he was made “night general manager.”

“I never heard of such an animal but the general manager didn’t like to work at night, and they wanted to accommodate him,” said Bennett. “About five months after that they transferred me to run the Mint in downtown Las Vegas. It had been losing about $4.5 million a year. … I made some money that year starting out $2.5 million in the hole. The next year we made $9 million … and the year after I think it was $19 million.”

Del Webb later asked Bennett if he could manage both the Mint and the Sahara Tahoe. He answered, “I can if you buy me an airplane.”

“No damned airplanes,” roared Webb. “Air West has all kinds of them.”

Bennett took on the additional job anyway at no additional pay. He was annoyed about both conditions, though. He had noticed that the Webb organization seemed able to train or hire bright managers, but they moved on to become stars in other resorts. He attributed the turnover to Webb’s pay structure. “I was managing two hotels, and the rest of the managers had one each, and we were all paid the same $150,000 a year, whether you were making money or losing money.”

His future corporation, Circus Circus, would be noted for paying some of the highest executive salaries in the business.

Webb did reward Bennett with stock options, and Bennett said he realized $5 million on the stock. Bennett left the company in March 1971, and teamed up with Bill Pennington of Reno to form a company that leased novelty electronic gambling machines to casinos.

In May 1974 the partners leased the troubled Circus Circus casino from its founders, Jay Sarno and Stanley Mallin. An option to buy came with the lease, and the partners eventually exercised that option in a complex transaction that would not be complete until 1983.

Bennett acknowledged Sarno as “the greatest idea man to ever hit Las Vegas,” and is close-mouthed about any mistakes he made. (Other industry watchers, however, say Sarno’s biggest mistake was opening with no rooms at all, in the mistaken belief the unusual casino would attract all the players it needed from less interesting properties.) Bennett prefers to talk about changes he and Pennington wrought, starting by adding a 395-room tower.

The hardest change, Bennett said, was bringing Circus Circus’ unique carnival-style midway under management control. “We had a few problems with concessions fleecing the customers, or at least conducting their operations in a way that made people angry,” said Bennett in 1975. Bennett and Pennington closed down the questionable operations and converted most to a midway department answerable to the hotel.

The partners had noticed most casinos seemed to mismanage slot machines.

They figured this resulted from putting casino managers in charge of slot machines. “A casino manager is always a person who came from the live gaming end of the business so he doesn’t usually care very much about slots,” explained Bennett in 1975. “Yet it is well known that the slots are one of the more important aspects of the business.”

They established a slot department with a head answering directly to the resort president, and found their slot machines soon were better chosen, better maintained, better located, more popular and more profitable.

Bennett admitted he might not have chosen middle-American families as his market, but the Circus Circus theme locked him in.

Mel Larson, a retired Circus Circus corporate vice president whom Bennett originally hired to market the casino, said, “I found out that half the people coming to town did not have reservations, and more than half were driving, so we just hammered radio on the stations that reached people on the freeway. We captured all this walk-in business, which was unheard of at the time. … Mr. Bennett and I spent a whole day coming up with the theme: `Rooms available, if not we’ll place you.’ And I put it on the marque the same day. … We advertised on rock stations, country stations, gospel stations … everybody else was after the upper income people, but we just wanted a lot of folks.”

The hotel sponsored special events which appealed to that market. Bennett rode motorcycles and personally owned and flew two of the finest stunt airplanes ever built, and Larsen had been a stock-car racer. So Circus Circus became an important name in hydroplane racing and motor sports.

The partners opened a property in Reno in 1978, and expanded it to 725 rooms in 1981. Pennington became its on-site manager; he retired in 1988. Bennett concentrated on Las Vegas. In February 1983 they bought the Edgewater Hotel and Casino in the emerging Colorado River resort of Laughlin.

Meanwhile, the partners took the stock public on Oct. 25, 1983, at $15 a share, and it hit $16.87 before closing on its first day.

Corporate counsel Mike Sloan, one of the few executives from the mid-1980s who is still with the corporation, said the stock performed well because Circus was especially able to take advantage of growth opportunities presented at the time. “Circus was the first public company to go to Laughlin, during a time Laughlin was booming. Laughlin, particularly, had Circus Circus demographics, a gaming city patronized largely by people who traveled by auto or RV, and perhaps combined gaming vacations with camping and water sports.

“The quickest way to grow your earnings is to grow your capacity, and ours was the fastest expansion of any major gaming company of the time,” continued Sloan.

By this time, however, other players were in the building-fast game, and Circus Circus sought to make its resorts outstanding in other ways. Acquiring a new site at Tropicana Avenue and the Strip, the company resumed founder Sarno’s practice of establishing some exotic theme and carrying it out in such detail that a visit to the resort became a pleasurable escape from reality. The theme of the $300 million Excalibur, opened in 1990, was the legend of King Arthur, and it was carried out in a 4,000-room storybook castle.

By 1993, the year Circus Circus opened the $375-million, Egyptian-themed Luxor, the company was Nevada’s largest employer, with 18,000 employees.

In 1999, after Bennett’s departure, the company opened the Mandalay Bay, aimed at a more upscale patronage but again using an exotic theme. The company then renamed itself for the upscale property.

Bennett himself was worth $600 million, according to the Forbes list of the 400 richest people in America.

Bennett could be a hard taskmaster. According to Larson, Bennett figured that since he gave department heads almost total authority, their main problem would be finding enough time to do all the tasks they would set for themselves. One executive, said Larson, made the mistake of asking Bennett if he had something else for him to do, because he had some free time on his hands.

“He said, ‘You can go look for another job, because you don’t have one here,'” Larson related. “He figured if the guy had to ask for work, he didn’t know how to run his department.”

Joyce Gordon, who worked more than 20 years for Circus Circus as a publicist during Bennett’s tenure there, remembered, “When you met Mr. Pennington, it was almost like you went over and hugged him. But you wouldn’t think of hugging Mr. Bennett. Yet … I never met a person who worked for him who didn’t worship the ground he walked on.

“If you approached a door at the same time Mr. Bennett did, he would reach forward as a gentleman does and hold the door for you. And it didn’t depend on your rank; I have seen him do that for a cleaning lady.”

Bennett kept his family life relatively private. He was widowed and remarried. His two grown children, Diana and Bill Jr., worked at Circus Circus, where their kinship to the owner reportedly was concealed.

Bennett believed in sharing the hotel’s financial success with the lower-level employees. While he was in charge, Circus Circus agreed up front to pay whatever wages were eventually negotiated in a townwide union contract. When the Frontier Hotel held out for a contract more favorable to management than the other hotels signed, Bennett started feeding pickets from Circus Circus kitchens. He kept doing it even after he left Circus Circus and moved to the Sahara, and to the bitter end when the Frontier owners sold the hotel in the strike’s seventh year. By then he had spent nearly $1 million feeding pickets, according to a union source.

In the mid-1990s, stockholders and higher executives began to question Bennett’s leadership. At a stockholder’s meeting in 1994, shareholders peppered the 69-year-old Bennett with pointed “questions about everything from the exodus of top executives … to the quality of the `Winds of the Gods’ stage show at the pyramid-shaped Luxor,” reported the Review-Journal. The previous fiscal year had been the first in a 21-year history as a public corporation in which the company’s net income declined. The stock price had dropped from $49 3/4 to 22 3/8. Bennett blamed the decline in earnings on pre-opening costs for the giant Luxor and for the Grand Slam Canyon theme park at the original Circus Circus. He predicted a quick turnaround.

But before the year was out Bennett stepped down as chairman. Even that didn’t quiet the criticism; Bennett became involved in a dispute over his attempt to purchase the site of the old Hacienda Hotel. Bennett attempted to buy the property personally; since Circus Circus was also an interested potential buyer, his critics charged that he had violated his responsibilities as a Circus Circus board member. It led to a lawsuit, and in a 1995 settlement, Bennett relinquished all claim to the property and resigned from Circus Circus. The property became the site of Circus Circus’ most luxurious property, Mandalay Bay.

Bennett sold his stock in Circus Circus for $230 million, and bought the aging Sahara for $193 million. Despite suffering a heart attack in 1996, at age 71, Bennett remodeled it in a heavily Moroccan theme, greatly enlarging the casino and adding a variety of virtual-reality family attractions related to his beloved motor sports. And old patrons of Circus Circus, walking through the hotel, see face after familiar face, veteran casino workers who accepted Bennett’s offer of benefits and pay equivalent to the jobs they were leaving. They’d bet on Bennett before, and believed.

Part III: A City In Full