Reed Whipple

One afternoon in the spring of 1986, Reed Whipple lay down on the carpet in his den to take a nap. At age 81, it had become part of his daily routine. But after three hours, his wife, Birdie, went to check on him. He had died in his sleep. Quietly. At peace with himself and his God.

Meanwhile, out on the end of East Bonanza Road, the initial earthwork was under way for the foundation of what would be the Las Vegas Temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

It was as though the Mormon leader’s work on Earth had concluded.

Whipple was first and foremost a religious leader. But he also was a civic leader, serving on the Las Vegas City Commission during two decades of phenomenal growth.

“He was a straight, no-nonsense person, and I don’t think he had any interests other than serving the people and city of Las Vegas,” says former Mayor Oran Gragson. “When I was first elected (in 1959) I relied on his counsel in many matters.”

Reed Whipple was born the same year as the city he would serve, 1905, in Pine Valley, in the mountains 30 miles from St. George, Utah.

He was the second youngest of the 11 children of Edgar and Althea Whipple, both faithful Mormons who reared their children in the church.

Edgar Whipple operated a sawmill, which provided a small cash income, and made the red bricks from which he fashioned a sturdy, two-story house, where Reed was born.

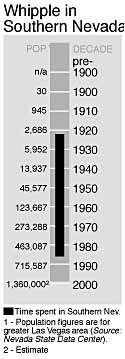

By 1917, most of the older Whipple children had married and moved away, many to the country along the Virgin and Muddy rivers of Southern Nevada. Father Whipple decided to do the same and, in September of that year, the family set off with a wagon piled high with household goods and driving a herd of cattle ahead. They spent seven days covering the 140 miles to Logandale, where Edgar Whipple purchased a 40-acre farm for $8,000 and planted a cash crop of cantaloupes to pay off the mortgage on the new place.

In 1918, the entire family was stricken by the Spanish influenza epidemic that swept the nation that year.

“The high fever … caused me to lose much of my hair and left me partly bald,” Whipple later recalled.

At age 17, Whipple moved to Las Vegas, where he graduated from the old Clark County High School. Following a stint with the Union Pacific Railroad, the 21-year-old went to work in 1926 for First State Bank as a bookkeeper at a salary of $145 per month. He would remain with the bank, after its acquisition by First National Bank, until his retirement in 1970, when he had reached the post of vice president.

In 1947, Whipple was elected to his first term on the Las Vegas City Commission. Though the position was nonpartisan, Whipple was a Republican and was fiscally conservative. In later years, he would often note that during his tenure, the city never had to take an emergency loan from the state, a remarkable feat, given the postwar population boom that kept city leaders scrambling to provide needed services. Of his first term, he said in 1979, “The financial situation of the city looked rather dim. We were borrowing money to meet our payroll and we had to make four or five substantial loans to run the city. However, all our loans were paid off prior to their due dates, and today we are one of the most financially stable cities in the country.”

Gragson recalls that it was Whipple who conceived the idea of municipal parking garages downtown. Whipple negotiated the deal whereby the Foley Federal Building was located downtown. The property was, at the time, owned by the Clark County School District, and a deed restriction prohibited the land from being used for anything except educational facilities. Whipple snipped the red tape and provided the feds a clear title.

The only public building bearing Whipple’s name is the Reed Whipple Center at 821 Las Vegas Blvd. North. It was originally opened by the LDS Church in September 1963 as a combination church administrative building, stake center and multipurpose recreational facility, including indoor basketball courts and outdoor softball fields. Its cost was about $600,000, and it was sold to the city in 1970 for $1,067,000. It has since been remodeled and opened as the Reed Whipple Cultural Arts Center.

In 1955, Whipple was appointed as the city’s delegate to the Clark County Fair and Recreation Board, which was finalizing plans for the Las Vegas Convention Center. Following its completion in 1959, Whipple served until 1967 on the board, which evolved into the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority.

Whipple was active in practically every charity and service organization in town. His favorite was the Boy Scouts of America. An Eagle Scout himself, he served as president of the Boulder Dam Area Council of the Boy Scouts, and in 1953, received scouting’s highest award for adult volunteers, the Silver Beaver.

Whipple was offered the state GOP candidacy for governor in 1950, but he declined to run, preferring to stay in Southern Nevada.

In the 1967 City Commission race, Whipple was unseated by tavern owner and political newcomer Jim Corey.

“If there was any single cause for Reed’s defeat,” says Gragson, “it was the widening of Maryland Parkway and Eastern Avenue.” The former mayor explained that in the late 1960s, portions of those thoroughfares were narrow, residential streets. Turning them into the arterials they are today upset those who owned homes along them, and it became a campaign issue.

“But it had to be done,” he says.

Whipple was ready to turn his full attention to church work, anyway.

In 1926, when Whipple arrived, Las Vegas had only the Las Vegas First Ward. It was part of the Moapa Stake. (A stake is a district of six to 10 wards.) In 1944, he was named bishop of the First Ward. In 1946, he was chosen president of new Las Vegas Stake and held that office until 1970, longer than any other Las Vegas Stake president before or since. During that tenure, he conducted an ambitious but necessary building program. And he did it at a time when local congregations were expected to raise most, if not all, of the money for those buildings. Today, the church headquarters in Salt Lake City typically funds 100 percent of new facilities.

“The church experienced tremendous growth … during this time,” Whipple wrote in 1979, “It has grown from two wards to 46.” There now are about 120.

In 1970, he retired from his banking job, and was named president of the St. George (Utah) Temple.

“Of all my church positions and service, being president of the St. George Temple was the most rewarding,” said Whipple.

To the LDS faithful, the temple is the most sacred of places, and is open only to members in good standing, who must be recommended by their ward bishop.

In 1971, Whipple was hospitalized with a heart attack, but was back on his feet in time to oversee a massive renovation and expansion of the St. George Temple.

Released from his temple duties in 1979, Whipple returned to Las Vegas with the title of stake patriarch, a position in which, according to LDS belief, he is authorized to bestow divine blessings or guidance on people.

That same year, the Washington County News in St. George reported that Whipple had been named to chair a committee charged with “attracting philanthropic support for LDS programs.” In fact, the primary purpose of the committee was to raise funds for a Las Vegas Temple. At the time of his death, the building fund contained some $5 million, enough to commence work.

Today, though, his name is not as well known to the general public as it was during his lifetime. Among Mormons, he is legendary.

“I know of no one individual,” eulogized church official G. Dwayne Ence, “that can match his record of unselfishness.”

Part III: A City In Full