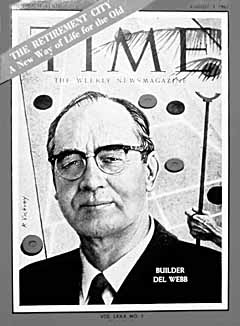

Del E. Webb

Del Webb had friends in high places and low, and was not yet sure where he should count Ben Siegel, his new client. Webb, a Phoenix construction man with a can-do reputation, had taken on an unfinished Nevada hotel as a favor to a banker friend with serious money at stake. Before he knew it he found himself bound by contract to a man of doubtful repute.

And before very long, Siegel would remove all doubts. Siegel bragged that he had personally killed 12 people. Now another mob figure was getting under his skin. “I’m going to kill that S.O.B. too,” Siegel added.

Webb’s face must have reflected his shock, for Siegel then reassured him:

“Del, don’t worry. We only kill each other.”

Webb walked a thin and dangerous line with Siegel, but it was all in a life’s work. Construction contracting was inherently risky. Somebody in his company once pointed out that it was a business where things do not even out. Bid too low, you lose money. Bid too high, you don’t even get the job.

Even by construction standards, Webb was daring. He took jobs nobody else had tried, finished them fast, did them well. He helped shape not only Nevada but its gaming industry, the entire American Southwest and even major league baseball.

Born to a wealthy Fresno, Calif., family in 1899, Webb saw his father go broke about 1914. His father lost his shirt in construction.

Webb originally had learned carpentry as a hobby. He turned to it as a livelihood, dropping out of high school.

But his main job, as he saw it, was playing baseball. Webb played for minor league teams in Oakland, Alameda, Modesto and other places, sometimes under an assumed name. A pitcher, he might have made it to the big leagues, but for an exhibition game at San Quentin prison in 1927. He caught typhoid fever from an inmate, nearly died of it, and for a year was unable to play baseball.

More than 6 feet tall, he normally weighed 200 pounds; his weight dropped to 99. Webb and his young wife, Hazel, moved to Phoenix in hopes of recovering his health. He did. He even played baseball again.

Margaret Finnerty, who wrote a biography of Del Webb, encountered at least three versions of how he got into the contracting business; two of those were from reputable journalists quoting Webb himself. All versions, however, involved a construction job gone bad.

“The guy I worked for was kinda on a shoe string,” Webb said in one case. “We would need material, and he’d show up with a board or two and then disappear. … One Friday I drew my pay check from this guy and walked to the bank. I figured I’d check out and maybe go to the Grand Canyon, where I had heard there was some work. The bank refused to cash the check, saying it wasn’t any good. … The next day (the client who needed a building faster than he was getting it) came to me and said, ‘You seem to know what you’re doing. Why don’t you go ahead and finish this building?’ From then on I was in the contracting business.”

Webb’s total beginning assets in 1928 are now legendary: “A concrete mixer, 10 wheelbarrows, 20 shovels, and 10 picks.”

The Los Angeles Times reported, years later, that the company was a $3 million operation by 1933, the height of the Depression. In 1935 Webb opened a branch office in Los Angeles. In 1938 he built an addition on the Arizona State Capitol.

Webb had great personal will power. In the 1940s he came down with what was presumed to be flu. A doctor began asking him routine questions for medical background.

“When I told him I drank 10 to 20 bourbons a day, he damn near dropped his teeth,” Webb related later. “He said I ought to cut down but I told him I damn well would quit. And I did. Not another drop of whiskey has passed my lips since that day. All that time I spent drinking I could now spend working.”

Herb McDonald, now director of special events at the Showboat and formerly a vice president of Del Webb Hotels, remembers that Webb ordered the same meal every time they dined together. “New York steak, green beans, no bread, maybe a baked potato, and one scoop of vanilla ice cream.”

Most construction companies banged together job-site shacks of unfinished framing lumber, but Webb used portable offices — identical in color, furniture and what went on inside. A manual outlined procedures, down to where where a given report would hang on the office wall.

That organizational mania paid off richly in the frantic opening days of World War II, when new military facilities and war plants had to be built yesterday.

World War II made Webb rich.

Having seen his father lose everything in construction, Webb put some eggs in other baskets. It was in that mood that Webb struck what he would call “the best deal I ever made.” With a partner, Al Topping, Webb acquired the New York Yankees in January 1945. The acquisition included not only the famous club but its farm teams, for a total of 450 players. And it included stadiums in New York, Newark and Kansas City.

The partners paid $2.8 million and promptly sold some unneeded land for $2 million. They would sell the club itself at the end of the 1964 season for $14 million. In the intervening years, the Yankees won 15 pennants and 10 World Series.

Yankees tickets clinched deals for corporate construction contracts and made Webb a friend to senators with porkbarrel projects to build.

Webb claimed he didn’t quite understand who Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel was when he agreed to finish Siegel’s new Las Vegas hotel. Robert Johnson, a longtime employee Webb assigned to work on the Flamingo and who later became president of Del Webb Corp., remembered that the job was plagued by elegant, but ill-conceived, design. “We never had a complete set of plans. We would build what he wanted, and then the architect would draw what we had built.”

Webb went on to build dozens of important structures in Las Vegas, including its present City Hall and Clark and Valley high schools.

It would not be Webb himself but one of his employees who would put the corporation into the casino business. It was L.C. Jacobson, an ex-carpenter who Webb hired as a timekeeper in 1938 and who eventually served as the company’s president from 1962 to 1966. In 1965 Jacobson told Fortune magazine that his original interest in gambling was shooting the dice. “I was never what you’d call a high roller, but I’ve taken my share of lickings up there — up to $9,000 or $10,000 on a few nights. … I thought it was high time I got some of it back.”

That hobby made him the acquaintance of Alfred Winter, who ran gambling operations illegally in Portland, Ore., and later legally in Las Vegas. In 1951, Winter wanted to build a bigger joint but didn’t know how to raise money. He asked Jacobson for help and got it; Jacobson, then executive vice president for Del Webb Corp., also landed the construction job for his company. And in return for his help, Jacobson was allowed to personally buy 20 percent of the stock in the new hotel.

It was called the Sahara, and it became for some time the most prestigious temporary address a visitor or a top performer could have in Las Vegas.

In 1961, Jacobson brokered a deal turning over the interests of the Winters bunch, including himself, in exchange for 1.5 million shares of Del Webb Corp. stock.

William Bennett, who joined Del Webb Corp. not long after and rose to operate two of its hotels, explained, “All these hotels originally belonged to owners who owned a percent here, a percent there, which is a bum deal because those guys think they have a license to steal. And they don’t. Jacobson and Winters got tired of having 15 guys in the count room taking a little for their bosses. So they made a deal to sell the thing to Del Webb for stock, and that enabled us to clean it up.”

Del Webb Corp. had gone public in 1960, and the purchase marked the first entry of a respected public stock corporation into Las Vegas gaming. In those days Wall Street was afraid of gaming, and Nevada gaming authorities were afraid of Wall Street. After a series of scandals involving mob investments in casinos, Nevada had passed a law requiring licensing and background investigations for new casino owners. That rule seemed to eliminate public corporations, whose stock is traded every day.

Del Webb Corp., however, devised a system of operating companies which “leased” casinos. Bennett said the arrangement was a polite fiction. “You just ignored it and ran the whole place.”

Del Webb Corp. quickly expanded, buying the Thunderbird Hotel and the Lucky Club downtown. It expanded the Mint and it built a new casino at Lake Tahoe. In 1978 the company was the largest gaming employer in Nevada, with some 7,000 workers.

It isn’t clear whether Webb’s entry into Nevada gaming inspired Howard Hughes’ entry. They shared interests in flying and played golf together in the 1940s. After Hughes lapsed into eccentricity and reclusiveness, Webb was one of the few people Hughes would meet with face to face.

Johnson told Webb’s biographer how those meetings were arranged. “He would call Mr. Webb, give him directions like ‘Go 10 miles to a dirt road, then go five miles to the top of a sand dune, then blink your lights twice.’ They’d get together and talk until maybe 4 in the morning. But whatever Hughes wanted, the company did it.” Webb did more than $1 billion worth of business with Hughes.

Unlike the group of hotels that Hughes would assemble, Webb operations were innovative. It was the Sahara that sponsored the Beatles appearance in Las Vegas in 1964. Booking an act which then appealed mostly to teens, who couldn’t gamble, was daring.

Webb did not simply acquire classy hotels and wait for rich people to go on vacation. They targeted wealthy subcultures. The Sahara Invitational was a highlight of the PGA tour. The Webb hotels sponsored trap shoots, realizing that men and women who could afford to burn 100 shotgun shells every outing also might throw dollars at a hardway eight. In the 1970s, the Mint 400 off-road race exploited interest in trendy vehicles. The Nevada resort operations did the main thing they were supposed to do for Del Webb Corp. — insulated the company against misfortune in other endeavors. Webb’s planned communities, aimed specifically at the retirement market, are considered landmark innovations both in American sociology and American business, and they have been very profitable in the long run. But they weren’t profitable every month.

Del Webb Corp. officials acknowledge they weren’t the first to think of a retirement community, but nobody had done it on the scale Webb did. Nobody knew if a sizable market really existed; some thought the elderly would grow depressed and die early if separated from extended families.

Market research, however, disclosed that putting substantial distance between themselves and their extended families was a major benefit many Americans hoped to get out of retirement, and yes they would move to Arizona to get it. Del Webb Corp. struck a deal to gradually take over and develop a former cotton ranch as the first Sun City.

The opening of model homes on New Year’s Day, 1960 showed that the market for retirement communities was larger than expected. Del Webb Corp. had hoped to get 10,000 people over the three-day grand opening.

They got 100,000, and sold 237 homes on the first weekend.

The company continued its diversification program until early 1974, when Webb fell ill. Webb had taken care of his health religiously ever since the 1940s, and had a checkup at the Mayo Clinic every year.

He was famous for the “No Smoking” sign on his desk when most adult males smoked. Yet it was lung cancer that felled Webb. He died on July 4, 1974.

Webb’s marriage to his childhood sweetheart, Hazel, broke up in 1952. Nine years later he married Toni Ince, a millinery buyer for a Phoenix department store. Toni Webb survives him and lives in Beverly Hills. Neither marriage produced children and much of Webb’s fortune went into the Del E. Webb Foundation, which funds medical projects in Arizona, California and Nevada.

In 1988, the same year it sold its last Las Vegas resort, Del Webb Corp. brought the Sun City concept to Las Vegas with the construction of Sun City Summerlin for 14,000 seniors.

The company followed up with Sun City McDonald Ranch in Henderson, which will accommodate about 9,500 homes. And in October 1998 Del Webb Corp. opened models for Anthem, a master-planned community in southwest Henderson, which will include not only a section for the retirement market but also a gated country club community and a section of traditional homes.

Some 12,000 homes will accommodate a population projected at 30,000.

Webb’s final contribution to Las Vegas may be a sea-change in desert demographics. He found Las Vegas a fast, young city full of young men and women on the make. And his upscale retirement communities will leave it a gracefully-paced home for those who have it made.

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full