Howard W. Cannon

As soon as Howard W. Cannon was elected a U.S. senator, he began to look like one. He already had a great ear-to-ear smile, but he also got kind of jowly. He gained a reputation for frankness and for not making promises he couldn’t keep.

He was a master of the possible. Maybe that’s why President Lyndon Johnson called Cannon to the Oval Office for what the Nevadan was sure would be some of LBJ’s legendary “arm twisting.”

It was 1964, and the Civil Rights Act was being debated on the Senate floor. It was in trouble. Southern senators had begun to filibuster and the only way to stop it was a vote of cloture.

Nevada’s Sen. Alan Bible had already voted against cloture. Nevada had traditionally found it prudent to uphold other states’ filibustering rights. It was a handy tactic often used to thwart anti-mining or gaming legislature.

When it began to appear that one of his pet pieces of legislation was going to die on the floor, Johnson made an offer to Cannon.

“Lyndon was a real dealmaker,” says Cannon. “If you needed a deal made, he’d make one for you.”

So what was the deal? Johnson is dead and the 86-year-old Cannon won’t say. But remember the preceding words when we reach the subject of water.

The late Las Vegas attorney Bob Archie worked for Cannon from 1959 until 1967, first as an elevator operator, later as an administrative aide. As a black, he was curious about how Cannon planned to vote.

“So I went into his office and sheepishly asked,” said Archie. Cannon was mum, but told Archie to be in the Senate the next day.

Cannon moved for cloture, ending the filibuster. The Civil Rights Act passed on June 10, 1964 — by four votes. It is doubtful it would have made it to a vote had Cannon not acted. Not only had he done the right thing, but he had made a very wise investment in Lyndon Johnson, one that would pay his state huge dividends.

He also had taken a huge risk. In a state then known as “The Mississippi of the West,” his position on civil rights probably hurt him politically.

The New York Times once described Howard Cannon as “a rather colorless man, who has never cut a swath through Washington.”

Perhaps his understated manner and classic Western wry humor are not appreciated at the parochial Times. The Cannon countenance is craggy, usually staid, but can quickly change into a wrinkled grandfatherly grin or the steely-eyed stare of a stern two-star general — which he is.

As for swaths, Cannon cut one through the green fields of the federal treasury and sent the harvest home to Nevada.

He began life on Jan. 26, 1913, in St. George, Utah, the first of Walter and Leah Sullivan Cannon’s three children. His father was a rancher, dairy farmer, banker and St. George postmaster. The Cannons were of English extraction, converted to Mormonism in Liverpool.

Howard was especially fond of lassoing wild horses and breaking them to ride. Some he sold; some he kept. It was, he says with a shrug, “just a hobby.” But it got him a job. On one of those horses, he delivered The Deseret News to widely-scattered ranches.

There is a snapshot, dated 1931, of young Cannon astride a beefy-looking motorcycle. He smiles broadly as he sees it.

“Oh yes. It was a Harley-Davidson,” he says, then turns to his wife, Dorothy. “I think I’d like to have another motorcycle,” he says. One senses that the 86-year-old ex-biker is only half-kidding.

Cannon doesn’t recall the very first time he went aloft in an airplane, but thinks it was probably with an itinerant pilot who came through town offering rides. In any case, flying would remain his lifelong passion.

“I admit I was more than a little impressed by the glamour of flying in those days,” he said in 1971. “Lindbergh had recently made his epic ocean-crossing flight, and that added to the pilot mystique that dominated that era.”

Even earlier, he had taken up playing the saxophone and the clarinet, and by his early 20s, had turned professional.

“I was a very good saxophonist,” he says proudly.

Howard Cannon and his Orchestra, which varied in membership from five to 15, had no trouble finding gigs in nearby towns and at colleges. And they got a long engagement on a cruise ship, which took them to Yokohama and Tokyo.

All of which would seem to indicate that Cannon was unsure of his future. Not so. He would be a lawyer. He had always wanted to be a lawyer.

“I wasn’t even thinking of politics then,” he says. “I guess I just kind of sloughed off into politics.”

He graduated from Dixie Junior College, then went on to the Arizona State Teachers College in Flagstaff where he earned a bachelors in education. Then it was on to the University of Arizona at Tucson, where he earned his law degree in 1937.

Both Cannon and his roommate, Johnny Milner, managed to learn to fly while attending law school. Cannon financed his lessons with proceeds from his band gigs.

Milner scraped together enough money to buy a Waco biplane, and the pair worked local fairs, carnivals and aviation meets, performing aerobatics and taking paying passengers aloft.

The Waco burned up in 1937, and Milner replaced it with a two-place Stearman biplane, capable of advanced aerobatics. Then the Tucson Citizen newspaper offered them an aerial newspaper route, dropping bundles at rural Arizona towns.

“I jumped at the chance,” Cannon recalled in 1971. “Not so much for the money; in fact I didn’t get any pay. But I did get in flying time and above that, it was exciting.” Milner flew; Cannon dropped the bundles, aiming for fat bushes to break the fall.

He returned to St. George in 1938 and began his law practice. Shortly thereafter, he enlisted in the Utah National Guard, aware of sabre-rattling in Europe, but not expecting to see immediate military duty.

He did. He was called to active duty in early 1941, before Pearl Harbor, at the rank of first lieutenant. His initial assignment was with a unit of combat engineers, but the Army soon began searching its ranks for men with flying experience, and offering them transfers to the Army Air Corps. By then, Cannon had multi-engine and instrument ratings.

February 1944 found him in Exeter, England, a captain in the 440th Troop Carrier Group. When the war ended, Cannon came back not to St. George, but to Las Vegas. He resumed his law practice in 1946, shortly after marrying Dorothy Pace in 1945.

In 1949, he was named city attorney of Las Vegas and served three consecutive terms.

In 1956, Cannon unsuccessfully challenged Walter Baring in the Democratic primary for Nevada’s sole congressional seat. It was a brief setback. In 1958, as the Democratic nominee for the Senate, he beat Republican George “Molly” Malone.

In Washington, Cannon lost no time in revealing his legislative priorities. The first was maintaining American military superiority; the other was the economic development of his state. Often, these two goals were synonymous.

In his first term, Cannon was named to the Senate Armed Services Committee, where he would remain for 23 years.

But one of his greatest accomplishments had nothing to do with air. It was the Southern Nevada Water Project, which allowed the phenomenal growth of Las Vegas since the 1970s.

Under the Colorado River Compact, signed prior to the construction of Hoover Dam, Nevada was entitled to 300,000 acre-feet per year of Colorado River water. But because of the high cost of piping it in, no water was drawn until World War II, when the federal government ran a 40-inch pipe from the lake to the Basic Magnesium plant in Henderson.

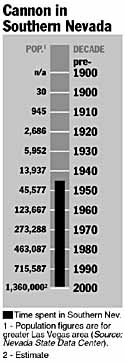

After protracted negotiations, the Las Vegas Valley Water District in 1955 began receiving water via the BMI line. But the pipe could not keep up with the meteoric rise in the city’s postwar population.

In mid-1965, Sen. Alan Bible and Cannon co-sponsored a bill that would fund construction of six pumping plants, a reservoir, a four-mile tunnel and 31.4 miles of pipeline to deliver water to every part of the Las Vegas Valley. It would cost $81 million, to be paid back over 50 years at 3 percent interest.

The bill rolled through the full Senate unopposed. It then moved on to the House of Representatives, and into the clutches of Baring, whom Cannon now admits he longed to punch in the nose “many, many times.”

Baring began raising semi-relevant questions about the bill, the amount of interest Nevada would have to pay. Even so, the bill passed the House 239-134, and went to Lyndon Johnson’s desk. The president had good relationships with both Bible and Cannon, but loathed Baring. LBJ sat on the bill for quite some time before Cannon surmised that the chief had a burr in his shorts. He paid the Texan a visit, assuring him that if he had any genuine concerns about the bill, they could be worked out. Johnson signed the Southern Nevada Water Project Act Oct. 25, 1965.

“I used a lot of my brownie points with Lyndon Johnson to get that on,” says Cannon firmly. “And I got it on. And nobody else had anything to do with it.” Actually, says Mike Green, a professor of history at the Community College of Southern Nevada, LBJ didn’t really have the luxury of alienating such staunch allies as Bible and Cannon. He sat on the bill, says Green, just to teach Baring a lesson.

Cannon fully backed Johnson’s conduct of the war in Vietnam, but in 1970 he opposed President Nixon sending U.S. troops into Cambodia. In 1972, he was openly critical of Nixon’s decision to mine North Vietnamese harbors.

“It is questionable,” Cannon said, “whether the president’s decision will have the desired effect of stopping the flow of supplies and material to the North Vietnamese without provoking a wider war or forcing a confrontation with the Soviet Union.”

Which is not to say that he had grown soft on national defense — especially the development of new and better war birds. In fact, he personally test-flew all new aircraft before voting for money to develop them.

“We flew some that shouldn’t have been flying, probably,” Cannon laughs. “There were a few clinkers.”

Some of the nonclinkers he piloted are the F-14, F-15 and F-111 fighter planes. He carefully monitored the progress of the F-117 stealth fighter, developed at the super-secret Groom Lake facility of Nellis Air Force Base, which he says he visited “many times.”

“Sometimes we were afraid it wasn’t ever going to get off the ground,” he says. “But it became a real ‘hot flying bird’ in our jargon.”

Of his many military interests, none had more impact on Southern Nevada than his work to transform Nellis Air Force Base into one of the most important military installations in the world.

“Senator Cannon, along with Senator Bible, built Nellis Air Force Base,” said the late Gen. Zack Taylor, base commander from 1966 to 1969, who explained that the base was constantly on the appropriations chopping block. Cannon says he and Taylor analyzed the potential of the base, resulting in it being designated a fighter weapons training school, pioneering “real-time” dogfighting training for U.S. and NATO pilots.

But it was in civilian aviation that Cannon achieved what he regards as his most significant accomplishment — deregulating airlines.

His career was marred by a few accusations, most of which remain merely that:

- In 1964, Bobby Baker, secretary to the senate Democrats, helped organize a fund-raiser for Cannon. When Baker was later accused of tax evasion, larceny and fraud, Cannon was on the investigating panel and was accused of suppressing a document and of voting to cut the budget for the investigation.

- In 1980, the FBI intercepted an innocent telephone call between Cannon and Allen Dorfman, an official with the Teamsters Union Central States Pension Fund. But Cannon later asked Dorfman about a land purchase. Cannon was attempting to intervene on behalf of 50 constituents who wanted to buy nearby land to halt a high-density apartment project.

- In 1980, New York Times investigative reporters accused Cannon of profiting from the placement of an off-ramp on U.S. Highway 95 (the supposed amount was $27,000) and of lobbying to have the Mizpah Hotel in Tonopah, in which he owned an interest, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, thus making it eligible for a federal preservation grant. Cannon later said the grant amounted to $24,000 of a $4 million project.

So, if Cannon was a crook, he wasn’t a very ambitious one.

In 1964, Cannon was challenged by Nevada’s popular lieutenant governor, Paul Laxalt. From the start, Cannon realized it was going to be tough to beat the glib, boyish Laxalt. So did Lyndon Johnson, who called Cannon and made him an offer.

“I’ll come on out there and campaign either for you or against you,” drawled Johnson. “Whichever you think will do you the most good.” Cannon took him up on the offer.

Even so, it was one of the closest races in Nevada history. It took several days to get a final count, but when it came, Cannon had squeaked past Laxalt by 48 votes.

In 1970, Laxalt was again tapped by his party’s leadership to challenge Cannon. He declined, and Vice President Spiro Agnew personally called on Washoe County District Attorney William Raggio to carry the GOP banner. Cannon won by 24,349 votes.

Cannon rolled to victory again in 1976.

Cannon says he had planned to serve one more term when the 1982 elections rolled around. In the Democratic primary, Cannon was astonished when he discovered that his challenger would be Congressman Jim Santini.

It was a rancorous and expensive battle, which Santini lost. However, Cannon had been weakened by the fight.

Still, his foe was Chic Hecht, a virtually unknown former state legislator and longtime Las Vegas businessman who had hitched his wagon to Ronald Reagan’s star. He relied on slick “image” ads that portrayed Cannon as an old style “tax and spend liberal” of questionable integrity.

It worked, and Howard Cannon became a private citizen once again.

Though Cannon is reluctant to speculate on what might have been, he is certain of one thing: The Yucca Mountain nuclear waste dump would not be an issue today. As chair of the Armed Services Committee, he says, the waste dump proposal would have had to come before him.

“I think that it could’ve been headed off,” he says simply.RELATED STORY: Walking out of the War

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full