Walter Liberace

As he strolled down Fremont Street, the cherub-faced young man with the dark, wavy hair offered passersby a broad grin, his hand and a handbill that introduced him.

“Have You Heard Liberace?” it asked. If they hadn’t, Walter Liberace would first correct their pronunciation of his name, “It’s Liber-AH-chee,” then ask them to come to his show at the Hotel Last Frontier.

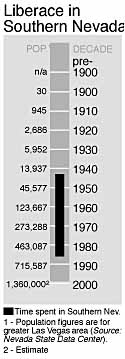

It was November 1944, and the young pianist was making his Las Vegas debut. The city would become the entertainer’s home — one of many around the country — but more important, it would become the place he would develop his spectacular stage persona. Liberace would pack Las Vegas showrooms for the rest of his life, and after his death, his collection of antiques, custom cars and elaborate costumes would fill a museum that is in itself one of the city’s more popular tourist attractions. The museum is the financial wellspring that funds scholarships for aspiring musicians and artists.

Asked in a 1985 interview how he wished to be remembered, Liberace replied: “I’d like to think that the most enduring quality about me will be the music, because everything I’m doing … is to promote the music of future talent.

“My foundation is based on promoting new talent, and I feel that my longevity will survive through other people in this business because I’m going to provide a lasting support and a foundation for artists.”

It was, after all, a scholarship that provided musical training for the boy who would become “Mr. Showmanship.”

Wladziu Valentino Liberace was born in 1919.

His father, an Italian immigrant who played French horn in orchestras providing background music for silent movies, required his children to learn music. Walter was capable of picking out tunes at age 4.

But he had difficulty speaking and had speech therapy, concentrating on giving his speech a smoother flow, eliminating the effect of listening to one parent who spoke with an Italian accent and another with a Polish accent. The result was a slow, deliberate style of speech.

The year 1929 marked the onset of the Great Depression and talking pictures. Mom worked in a cookie factory, brother George drove a a grocery truck and gave piano lessons, sister Angelina worked as a secretary and nurse’s aide. And Walter, still a pre-teen, played the piano for dance classes and washed dishes.

“Except for music, there wasn’t much beauty in my childhood,” he later recalled. “We lived in one of those featureless bungalows in a featureless neighborhood. I hated shabbiness. I’d walk 27 blocks and pay 15 cents to sit in a new, clean movie house when I could have walked five blocks and paid 5 cents to sit in an old, dirty one.”

He excelled academically at West Milwaukee High School, and was active in extracurricular activities, excluding sports. (He couldn’t stand to get dirty.) One of the school’s traditions was “Character Day.” Every student was supposed to dress up as a famous character from history, and Walter nearly always won. He appeared one year as Emperor Haille Selassie of Ethiopia, another as Yankee Doodle Dandy. One year, he came in full drag as Greta Garbo.

His big break came in 1939 with an audition for Dr. Frederick Stock of the Chicago Symphony. His audition was flawless, and he was invited to play at the Pabst Theatre in Milwaukee. In the meantime, he found a spot with the Jay Mills Orchestra, a popular dance group. When the band went on a radio show, and Walter was introduced, the manager of the Chicago Symphony heard it, and complained to Stock.

“I don’t care if he played on a street corner with the Salvation Army Band,” said the maestro. “He will play with us.”

The symphony asked only one thing of Liberace; that he change his name until after the concert. That was why, for the next six months, Walter Liberace performed as “Walter Buster Keys.”

Sometime in 1942, perhaps emulating his idol, the great Polish pianist Paderewski, Walter Liberace dropped his first name altogether. His friends would thereafter simply call him “Lee.”

Liberace was moved by the film “A Song to Remember,” about the life of Polish composer Frederic Chopin. He was especially impressed by the elegant candelabrum atop the piano whenever Chopin played. He decided to borrow the image.

In 1944, while performing at the Mount Royal Hotel in Montreal, Liberace received a phone call from Maxine Lewis, entertainment director at the Hotel Last Frontier. She asked him if he would be interested in playing Las Vegas. He would. She asked how much he was currently making.

“Seven hundred and fifty a week,” he lied. His salary was $350, but Lewis agreed to $750 per week.

Liberace sized up his first-night audience, and decided to delete several of the classical pieces, concentrating on boogie-woogie and popular tunes. The audience went wild, and Maxine Lewis called him to her office, where she tore up the $750-per-week contract and gave him a new one for $1,500. Later, he would sign a 10-year contract with the hotel at an even higher salary.

In later years, Liberace never failed to recall for interviewers one rehearsal in particular. One afternoon he arrived for a rehearsal and found no one in the room to assist him except a tall, thin disheveled man standing next to a lighting board. Liberace walked up to him and began instructing him in what lights he wanted for which numbers. As he was delivering the spiel, Maxine Lewis walked up to the man, who nodded to her. Then she turned to Liberace: “I didn’t realize you knew Howard Hughes.”

His next encounter with a Las Vegas legend would be less embarrassing and a bit scarier.

In 1947, Liberace made a return engagement at the Last Frontier and, as usual, the audience loved him. After the show, he milled in the casino with the crowd, chatting and signing autographs. As Liberace biographer Bob Thomas tells the story, Liberace felt a hand grip his arm, and a gruff voice say, “Hey kid, I want to talk to you.” Liberace protested and moved away. The man followed. Liberace asked a security guard, “Who is that creep over there, the one who looks like a gangster?”

“He is a gangster,” said the guard, “That’s Bugsy Siegel.”

Terrified that he had offended a known killer, Liberace went to prepare for his second show. After, he received word that Siegel wanted to see him in the lobby. The Bug wasn’t angry, just trying to steal the Last Frontier’s headliner for his new Flamingo Hotel. He offered to double Liberace’s $2,000 per week salary.

“A classy act like you should be playing the Flamingo, not this cheesy dump,” said Siegel, who then left Liberace to fret over whether to accept the offer and insult his current benefactor, or refuse and risk a very abrupt end to his career. The problem solved itself a few months later when Siegel was shot dead in his girlfriend’s Beverly Hills, Calif., home.

George Liberace had become his brother’s road manager when he was discharged from the Navy, and Liberace also had hired a press agent, Sam Honigsberg. Together, their efforts saw Liberace’s name recognition rise dramatically. In 1948, he headlined at some of the most prestigious hotels in some of the largest cities in the nation — plus Las Vegas.

Liberace’s public persona, that of an effeminate mama’s boy, often brought caustic comments. At a concert in San Francisco, Liberace responded to his detractors with characteristic wit, “I don’t mind the bad reviews, but George cries all the way to the bank.”

The question of Liberace’s sexual orientation can still start an argument. But it is fairly certain that he was, indeed, gay.

“In fact,” wrote Thomas, “Liberace was confused about his sexual identity.” He explains that his first sexual encounter, with a female blues singer who practically raped him in a car, had “obliterated any boyish notions he had about romance.”

Aside from the occasional one-night stand, he seems not to have had a regular gay partner, at least in his early days. Publicly, he steadfastly maintained that he was just waiting for the right woman to come along, and even had some high-profile courtships to quell the rumors.

His most devoted fans, middle-age and elderly females, were, in his mind, the group most likely to desert him if he stepped out of the closet.

In the fall of 1956, Liberace toured Great Britain. Adoring crowds of women swarmed him at every stop, and groups of male homophobes screamed things such as “Queer go home” and “Send the fairy back to the States.”

A scribe for the tabloid Daily Mirror, William Connor, writing under the name “Cassandra,” wrote perhaps one of the nastiest reviews ever suffered by Liberace, called him “the biggest sentimental vomit of all time,” and went on to describe him as “this deadly, winking, sniggering, snuggling, chromium-plated, scent impregnated, luminous, quivering, giggling, fruit-flavored, mincing, ice-covered heap of mother love.”

It was that crack about “fruit-flavored” that prompted Liberace to sue the paper for libel, and caused him to bluster, “If … my appearances didn’t depend on my hands, I would knock Cassandra’s teeth down his throat. And I ain’t kidding.”

The British High Court ruled in Liberace’s favor, and a jury later awarded him $22,400 in damages.

But by the late 1950s, Liberace was letting his guard down more, inviting young men to his homes in Malibu, Palm Springs and Las Vegas. While few of his business associates ever recalled seeing him in the company of a male paramour, one person knew all too well of Lee’s secret dalliances; his brother, George. One day, he confronted his younger brother.

“Goddammit Lee,” he said, “how can you keep saying in public and in courtrooms that you’re not a homosexual and then hang out in the Springs with a bunch of faggots? You’re gonna get nailed someday.”

Furious, Liberace fired him, then rehired him under pressure from their mother, who boycotted Lee’s concerts until they reconciled. However, according to Thomas, it would be many years before they were friends again.

In the early 1980s Liberace hired an 18-year-old named Scott Thorsen as his private, live-in chauffeur, bodyguard and secretary. In 1982, Liberace had Thorsen bodily ejected from his house, ostensibly because of his drug use, and because he had made a death threat against the entertainer.

Thorsen filed suit for palimony, asking for $380 million, and claiming that part of his initial agreement with Liberace had been that sex would be part of his job description. Thorsen asserted that since he had been Liberace’s de-facto spouse, he was entitled to half of his assets. After some lurid testimony, a few spicy tabloid articles and some unnerving interviews by the media, a California judge ruled in Liberace’s favor, dismissing the palimony claims as being void because they were essentially a contract to perform an illegal act — prostitution.

Later, he would find a more suitable companion in 19-year-old Cary James, who was content to remain quiet.

Liberace was perhaps the most ardent collector of art, antiques and curios since William Randolph Hearst. Everywhere he went, he sought out antique stores, junk shops and garage sales. He bought rare pianos, one owned by Chopin, another by George Gershwin. Soon, like Hearst, he had filled warehouses to the ceiling with the objects he called his “Happy Happys.”

However, unlike Hearst, he wanted to display his goodies — all of them. So he bought houses, and incorporated his collections into their startlingly elaborate interior schemes. As his fortune grew, so did the number of customized houses he owned. He explained that while his profession required him to travel, he preferred to own homes in the cities where he worked most. In his life, he owned homes in Sherman Oaks, Hollywood Hills, Palm Springs, Malibu, Los Angeles, Lake Tahoe, Lake Arrowhead, New York and several in Las Vegas. When he was forced to stay in a hotel room, he often re-decorated it.

Always a fop, Liberace had, in his early years, appeared clad in the concert pianist’s uniform — black tux and tails. When he appeared at the Hollywood Bowl in the early 1950s, he had been concerned about being visible against the black-suited orchestra and had gone onstage in a white tux. At the conclusion of the show, someone asked him what he would wear at his next appearance, in Las Vegas. Standing next to him was a woman in a gold lamÈ dress.

“I’ll be wearing a gold lamÈ dinner jacket,” he answered offhandedly. He did. For Liberace, the fact that the audience responded to gay apparel was all he needed to know. Next came the diamond shirt studs, the multicolored tuxes, the capes and furs and boas and rhinestones and sequins, the dashes backstage with the parting quip, “Pardon me while I slip into something more spectacular.”

“I hate to admit it, but I just keep piling things on and on,” he later said of his act. Las Vegas, he found, was the perfect venue for his increasingly elaborate productions.

“These extravaganzas are a form of vaudeville, really, and I love doing them. There are only a few places left, like Nevada, where you have places that can handle them. In the other places, I have to simplify things a bit, like cut out some of the cars, or the dancing water, you know.”

He also noted that he had some competition in the garish costume sweepstakes. Elvis Presley, who had bombed in Las Vegas during his first appearance in 1956, was appearing regularly at the Las Vegas Hilton, and had abandoned his modest slacks and sport coat for garish costumes festooned with, of all things, rhinestones and sequins.

Liberace opened at the Las Vegas Hilton in 1972, lured by a salary of $300,000 per week. No other Las Vegas headliner made more. Las Vegas became his legal residence, and he played here about 16 weeks a year, four in Reno and Lake Tahoe. He decided to find a suitable Nevada home. He purchased an unremarkable tract home, then the adjacent house, and linked them together into one mansion. He then set about giving them the Liberace touch. A reproduction of Michelangelo’s painting of the roof of the Sistine Chapel loomed over his bed, an indoor lagoon had a miniature version of the “dancing waters” show and everywhere were marble, mirrors and gold.

He also decided that his collection of “Happy Happys,” which had grown to include several rare autos, works of art and a desk once used by Czar Nicholas II, constituted the raw material for a museum.

He found a moderately-priced shopping center on East Tropicana Avenue in Las Vegas and opened his museum personally on Easter Sunday in 1979.

The museum is a significant Las Vegas tourist attraction, drawing well over 100,000 visitors a year.

In August of 1986, Liberace returned to Caesars Palace for a two-week engagement. It was his final Las Vegas show. His friends, staff and the Caesars stagehands noticed that the normally ebullient and gregarious Liberace was quiet and spent most of his offstage time in his dressing room.

His obviously deteriorating health prompted many inquiries from the media. Liberace laughed them off, explaining that he had gone on a “watermelon diet” that had made him ill. But he was recovering nicely, he added.

He remained secluded in his Palm Springs home until he died Feb. 4, 1987, at age 67. The rumors that he was dying of AIDS began even before his passing, but were all dismissed by his staff and family. His Las Vegas physician, Dr. Elias Ghanem, would not comment.

His Palm Springs physician, Dr. Ronald Daniels, filed a death certificate stating that Liberace had died of heart failure, brought on by a brain inflammation.

However, before the pianist could be put to rest, his body was seized by Riverside County Coroner Raymond Carrillo and autopsied. Carrillo announced that Liberace had indeed been carrying the HIV virus.

Liberace was buried in a 6-foot tall tomb at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in the Hollywood Hills. The tomb stands between a pair of flowering pear trees trimmed to resemble candelabra.

He was eulogized in Time magazine as “a synonym for glorious excess,” and the writer went on to say, “Liberace was a visual, rather than an acoustic phenomenon. He charted a path followed by the unlikeliest of proteges, from Elvis Presley to Elton John and Boy George: the sex idol as peacock androgyne.”

Liberace was nothing if not an astute businessman, and he knew this of himself.

“I have more or less made Liberace a person other than myself,” he explained. “I’ve created a product for the public that the public has continued to buy and to remain interested in. I treat it as a commodity or product. Like General Motors creates a car.”

Part III: A City In Full