Otto Ravenholt

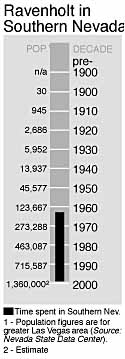

One afternoon in 1982, Otto Ravenholt, chief health officer for the Clark County Health District, was talking to a reporter about contagious diseases and what the doctor had done about them in his 19 years in office.

Ravenholt explained that the infant mortality rate had dropped dramatically. Tuberculosis, once common, was now rare, and venereal disease was dropping.

“I asked why the numbers were getting smaller,” said Mike Green, the reporter, and now a professor of history at the Community College of Southern Nevada. “He gave me detailed medical reasons for the decline of infant mortality and tuberculosis.”

“What about venereal disease?” asked Green.

“The economy,” answered Ravenholt.

“The economy?” asked Green, scribbling frantically.

“Yes,” said Ravenholt. “You see, when the economy is bad, people don’t have the money to do the things that give them VD.”

Green was impressed with the Ravenholt’s insight and frankness, and his longevity in the contentious world of local politics.

During his 36-year tenure, Otto Ravenholt created the Clark County Health District. He reformed the state’s 19th century mental health laws, and reduced infant mortality by providing more and better prenatal and infant care for the poor.

Perhaps his greatest achievement was setting very high standards for restaurant sanitation.

Otto Hakon Ravenholt was born May 17, 1927, on a farm in rural Wisconsin, one of the nine children of Ensgar and Kristine Peterson Ravenholt.

After graduating high school in 1946, Ravenholt enrolled in the University of Minnesota, working full time to pay his way.

In 1947, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, was sent to its language training school, and mastered Japanese.

After his discharge in 1952, he returned to college to pursue a medical degree. In 1958, Ravenholt earned his M.D., and served his internship at the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital in Seattle.

“I reasoned that getting a medical degree and going into public health would be the kind of community thing that interested me,” said Ravenholt. “All of my brothers and sisters more or less followed the public service track.” Among his siblings are two nurses, two physicians and a distinguished journalist.

In 1960, young Dr. Ravenholt was hired to head the Shawnee County Health Department in Topeka, Kan. During his three-year tenure, he supervised the completion of the new county health department, and traveled the state lecturing on health issues.

In January 1963, he met with members of the newly created Clark County Health Board for lunch under pink chandeliers at the Fremont Hotel. He wasn’t in Kansas anymore — and he liked it. He was hired at a salary of $22,000, and was scheduled to start on Sept. 1. Instead, he showed up in July to help persuade voters to approve a $1.2 million bond issue for construction of a new health center.

The bond issue passed and R-J political columnist Jude Wanniski wrote that Ravenholt “our new, exuberant County Health Officer … was just about the most gleeful fellow in town, kicking up his heels with great delight.” Then he went to work.

“Our infant mortality rate in Clark County is 50 percent higher than it is nationally,” he reported in October 1963. “Instead of 24 deaths per 1,000, we have 36 deaths per 1,000 — through bad prenatal care and poor care in the first months of a child’s life. There were 50 babies who died last year that could be living today if this department had been properly staffed.”

In the black community, the infant mortality rate was 45 per 1,000.

Not surprisingly, the city had an alarming amount of venereal disease, but no real program for education or treatment.

Animal control was spotty, and there was no countywide licensing or inoculation system for pets.

The area at the foot of Frenchman’s Mountain, around the old county landfill, and along Vegas Wash, was patrolled by packs of wild dogs, mostly litters of puppies dumped there and gone feral.

In early 1964, a North Las Vegas veterinarian destroyed some 15 dogs owned by people living in the eastern valley. They all had leptospirosis, a virulent disease that attacks the liver and kidneys, and is spread by dog urine. Ravenholt announced the outbreak, and calmly reassured the worried public. However, he used the occasion to point out the need for a coordinated animal control program, which was not long in coming.

One of the biggest health issues in the Las Vegas Valley during the 1960s was air pollution.

The dust storms that periodically cloaked the valley were truly dangerous. The valley building boom resulted in hundreds of square miles of land being denuded. The storms were fierce, of dust-bowl magnitude.

The solution was ridiculously simple, and Ravenholt implemented it. That is why today, whenever one sees graders leveling a new building site, there also will be a water truck or two following along, wetting the loose dirt to keep it in place.

By the early 1960s, Las Vegas’ resort owners were beginning to realize that a tourism-dependant town could ill afford to give its guests food poisoning. Bad for repeat business.

Ravenholt had a radical idea. What if the department employed only credentialed sanitarians and paid them a liveable wage?

“There was a need for stronger sanitation control in the food facilities in the hotels,” said Ravenholt. By the 1960s, he said, Las Vegas had become a dumping ground for worn-out restaurant equipment from Los Angeles. Refrigerators that didn’t get cold, freezers that didn’t freeze, lukewarm steam tables. Since the key to avoiding outbreaks of food poisoning is to keep foods sufficiently hot or cold, faulty equipment could make people sick.

“We locked the door against used equipment being shipped into Las Vegas,” said Ravenholt.

Of course, to some Strip bosses, Ravenholt seemed a zealot, meddling in their business. In 1964, the Flamingo decided to test his resolve. An inspection of the hotel kitchen had shown it to be in deplorable condition, and Ravenholt politely asked to meet with the food and beverage manager at once to recite a long list of repairs and renovations that would have to be made at once. At the appointed time and place, Ravenholt and an aide were waiting when a cook and a dishwasher showed up. Neither knew why they had been sent. The gauntlet was down, and Ravenholt didn’t hesitate.

It was Friday afternoon, and he sent a message to the food and beverage manager, informing him that at noon on Monday, the restaurant would be closed unless substantial progress had been made to remedy the problems.

“They brought in quite a crew from Los Angeles, and they worked 24 hours a day to finish the job,” said Ravenholt. “That was a milestone in terms of credibility. They knew we could literally close their operation.”

In 1965, under a new state law, Ravenholt donned the hat of Clark County coroner and wore it 26 years through about 2,000 homicides.

“Prior to that, there hadn’t been any office of the coroner. The justice of the peace was coroner by statute …

“I’m sure the most challenging test in the coroner thing came with the policy I initiated of holding inquests,” said Ravenholt. The catalyst, he said, was the fatal shooting in 1969 of a 17-year-old black teen, Aaron Butler, Jr., by North Las Vegas Police. District Attorney George Franklin instantly ruled the shooting justifiable. Ravenholt was suspicious, and was further spurred to action by expressions of outrage in the press and from black leaders such as Charles Kellar, who called the shooting murder.

The police maintained that Butler reached under his jacket for what they believed was a weapon. An eyewitness claimed Butler had his hands in the air when he was shot. The weapon was a flashlight. Two days of testimony from 19 witnesses concluded the shooting was justified.

In early January 1967, Gov.-elect Paul Laxalt offered to make Ravenholt executive director of the Nevada Department of Health and Welfare.

“I was flattered by the overture. But it turned out that this was a much more persistent thing than just an invitation,” said Ravenholt. “For some reason, he was determined that I should be director.”

Laxalt persisted for several weeks, but Ravenholt had a personal reason behind his reluctance.

In the mid-1930s, the Ravenholt family homestead had been foreclosed, the family evicted. The children were dispersed to various farms, homes, old hotels and barns. Eventually, they were reunited on a rented farm. But father Ensgar Ravenholt had a long history of emotional problems, which became worse after the loss of his farm. He eventually was confined to the state mental hospital. His young son got a firsthand look at the barbarity of the mental health system.

“Unpopular family members, or those who were an embarrassment got committed in those days,” said Ravenholt. “Once in, getting out was tough, because civil rights had been suspended. There was no voluntary exit.”

So Ensgar Ravenholt escaped. A manhunt was organized, the radio blared warnings about the dangerous escaped lunatic. One evening, 400 miles away, he walked across a field and greeted his sons, who persuaded him to return. With the help of his close-knit family and therapy, he recovered, and spent the last 10 years of his life tending the Rose Garden in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park.

Ravenholt told Laxalt he would take the job for six months. He kept his old one, and commuted between Carson City and Las Vegas. In wooing Ravenholt, Laxalt had promised to support any measure the doctor proposed.

“Nevada had no out-patient facilities for the mentally ill,” Ravenholt recalled recently. “I wanted to modify the rules at the Sparks Mental Hospital and move mental illness treatment from in-patient to out-patient … we changed it to more of mental treatment than confinement.”

Ravenholt was both coroner and head of Clark County Emergency Medical Services in November 1980, when the worst hotel fire in the city’s history roared through the MGM Grand, now Ballys. He was in charge of recovering the bodies of 87 people who had died of burns and smoke inhalation, and transporting about 700 who required hospitalization.

Ravenholt knew that a procession of body bags on stretchers coming out of the hotel would attract TV cameras and photographers, and he wanted to avoid that. Oddly, the problem took care of itself.

“By 11 or 12 o’clock, there’d been an overload on the media, they had more than they could handle, and they were off to file stories and have something to eat.” The grueling job of hand-carrying the victims down from the upper stories began just after noon.

Ravenholt was amazed at what he found on the upper stories. Flames had not reached some floors, but poisonous gases from below had risen up the elevator shafts like chimneys, and leaked under doors. Many people were found sitting in their rooms, where they had been waiting calmly for the ruckus to pass, when they died.

“I remember one bell captain, in his uniform and all. He’d been sitting in a chair, looking out the open window with his feet up on the sill. The chair had tipped back onto the floor, and he’s sitting in this chair with his toes sticking up, dead. And that was the case with 10 to 20 people. They had died completely unsuspecting in those rooms.”

As he speaks of the MGM Fire, Ravenholt sounds oddly detached.

A bit of emotional detachment helps in politics, too.

“Frankly, in over 35 years in Las Vegas, politics were never a problem for me,” said Ravenholt. “With all the winds that blow one way or another, the personalities that rise and fall, I never had any serious distress about the politics of Clark County and Las Vegas. I had a pretty good talent for friendships and comradeships when they elected someone, and at the same time for not getting too close to them. That’s what gets you in trouble; you get tied up with one faction or another, and you become one of the strong boys’ people. And you get to where you’re keyed to what he wants, and the others get angry with you because you’re in his pocket.”

Then he smiles, thrusts out his FDResque chin, and peers over his trifocals.

“Of course, one of the best advantages you can have politically is if people underestimate your ability to play the game.”

Part III: A City In Full