Biggest outbreaks in US of deadly fungus strike Southern Nevada

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has sounded the alarm on the growing threat posed by a drug-resistant, potentially lethal fungus that has triggered the largest outbreaks in the country at Southern Nevada hospitals and long-term care facilities.

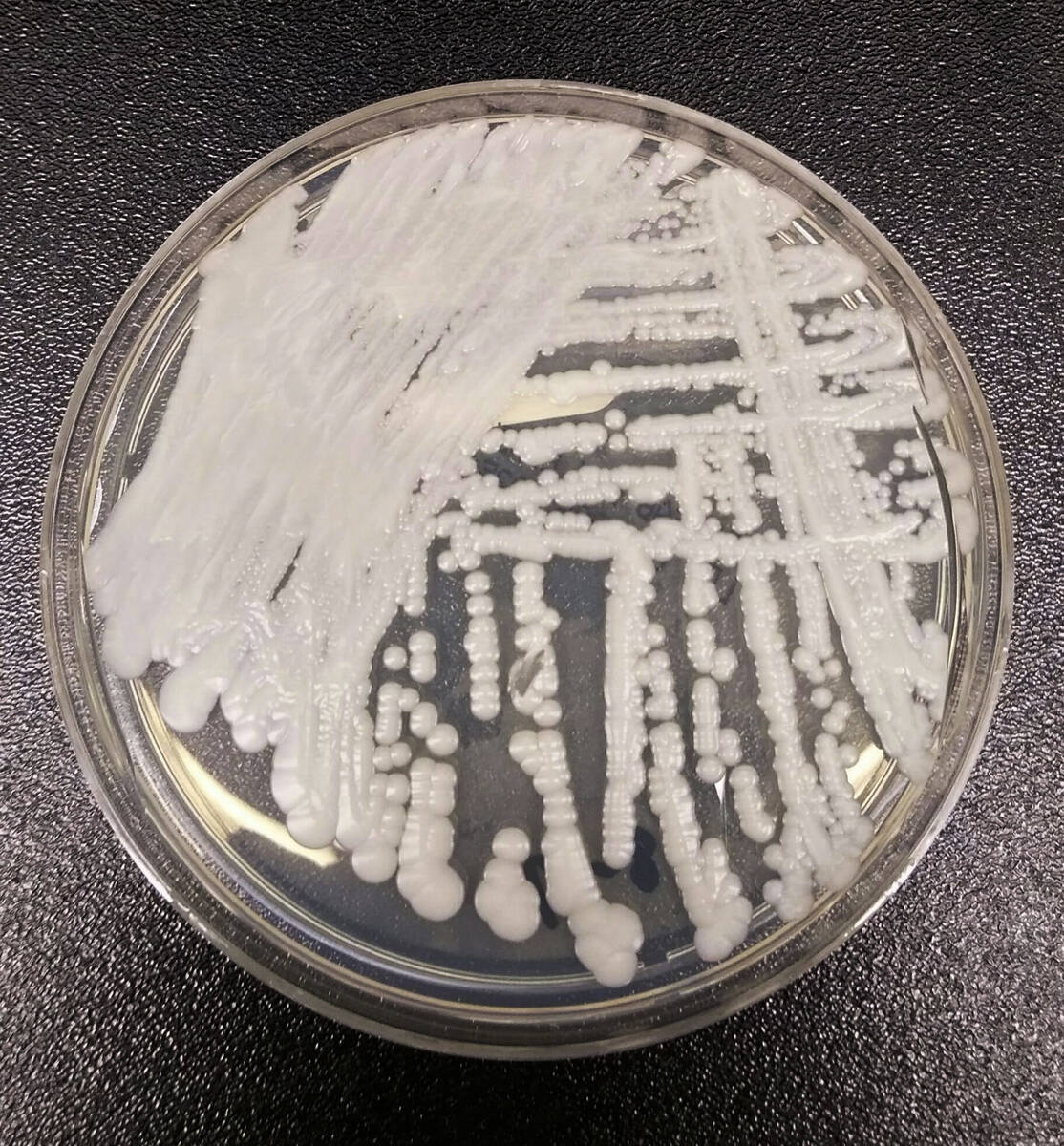

The Candida auris fungus has spread at an “alarming rate” in the U.S., with a tripling of the number of cases resistant to the most recommended antifungal used to treat infections, the federal public health agency said March 20. Its data was included in a new study published on the same day in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Eradicating the fungus in places where it has taken hold is unlikely, the study’s lead author told the Review-Journal on Wednesday.

“It’s more challenging if you detect this situation after there’s already been some transmission for some time undetected,” said study author and CDC epidemiologist Dr. Meghan Lyman.

This scenario has played out in several places, she said, including Southern Nevada. Last year, Nevada reported the highest number of cases of any state, according to CDC data.

In April of last year, the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services alerted health care providers of outbreaks of the fungus in Southern Nevada, as first reported in the Review-Journal. The earliest cases were identified in August 2021.

In 2022, Nevada reported 384 of the country’s 2,377 clinical cases of C. auris, according to CDC data. At least 27 states and the District of Columbia have reported cases, with the earliest infections in the U.S. reported in 2013.

Since August 2021, more than 1,000 people in Southern Nevada have been infected with the fungus, according to data from the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory at University of Nevada, Reno’s School of Medicine. There has been only one detected case in Northern Nevada, in Reno in 2019. One hundred C. auris patients have died, according to the lab’s data.

Nearly 500, or almost half, of Southern Nevadans identified with the fungus had clinical cases, such as an invasive infection of the blood, heart or brain.The remainder were colonization cases, in which the fungus was detected living on the person’s skin but had not caused an infection.

The fungus typically doesn’t pose a threat to healthy individuals. At highest risk for infections are patients with lengthy hospitalizations, with a central venous catheter — also known as a central line — or other lines or tubes entering their body, or who have previously received antibiotics or antifungal medications, according to the CDC.

The fungus can spread from colonized individuals who don’t know they have it. It also can spread from surfaces — such as a bed rail or a piece of equipment — where it can survive for long periods of time.

Not the new COVID

Candida auris isn’t viewed by health authorities as the next COVID-19, which spread widely through ordinary activities and infected — and sometimes killed — previously healthy people.

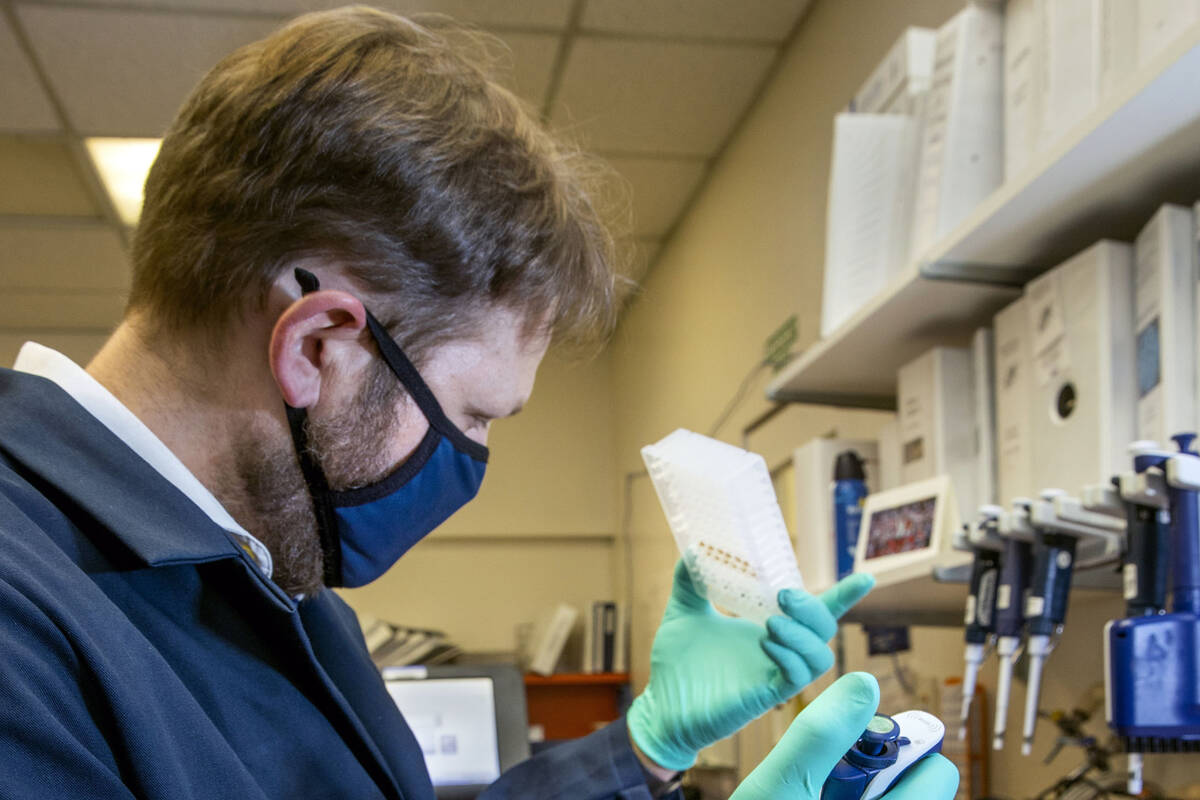

David Hess, a genomic scientist with the state public health lab, said C. auris is more comparable to MRSA, a drug-resistant staph infection that also is associated with health care settings.

In other words, it’s a serious threat to public health. To better track the threat, the lab, after it received notification about the outbreaks, began a year ago to conduct whole-genome sequencing, an advanced technique of genetic analysis, on specimens from every positive test result for C. auris.

The lab’s scientists have found that the fungus is mutating in ways that make it resistant to the preferred antifungal drug for treating it, a development the lab’s molecular supervisor, Andrew Gorzalski, described as alarming.

Just three classes of antifungal drugs are in use, the scientists said. Most cases of C. auris are naturally resistant to one type, azoles. A second type, polyenes, may cause fevers and tremors in patients, giving it the unfortunate nickname of “shake and bake.”

In 2 to 3 percent of cases, C. auris is showing increased resistance to the preferred treatment, echinocandins, laboratory analysis shows.

“We’re seeing that resistance evolve in the Nevada outbreak where we did not see it before, and that’s something we’re still sort of getting our hands around,” Hess said.

Nevada is doing the most real-time screening for fungus drug-resistance of any state with an outbreak, he said. By quickly identifying drug-resistant cases, authorities can work with doctors and health care facilities to focus on stopping their spread.

“We think that’s going to be one of the best strategies going forward,” Hess said.

The CDC’s Lyman noted that new antifungals are being developed and that the federal government will consider authorizing existing FDA-approved antifungals for other conditions to treat invasive C. auris cases.

Tracing a pathogen’s path

Through its genetic analysis, the state lab also has been able to trace the path of the fungus. It initially found three separate clades, or strains, in Southern Nevada. One quickly died out. The other two spread among medical facilities.

The two other strains were initially identified in cases at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center and Centennial Hills Hospital Medical Center, Shannon Litz, a spokesperson for the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services, said last year.

Two additional strains have been identified more recently, including one from Texas. Analysis indicates that patients from Nevada have introduced strains in Arizona and Utah, Gorzalski said.

The fungus has been identified in more than 30 hospitals and long-term care facilities in Southern Nevada, according to data last year from the Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health. The department did not provide a requested update on the data.

Candida auris is rising everywhere across the country and around the globe, not just in Nevada. “We had the biggest outbreak, it kind of got established, but this is something that’s being seen everywhere,” Hess said.

To help stop transmission, the lab offers free, rapid turn-around testing to screen high-risk patients for C. auris, such as those being admitted to a long-term care facility after transferring from a hospital. Identifying a case at admission allows precautions to be taken before more people become infected.

Speaking generally about cases in the U.S., Lyman said, “I think that there are definitely opportunities for improvement with identifying cases, either through clinical specimens or screening. Oftentimes cases are identified late, or after they’ve been in a facility for a while, and have had the opportunity to spread to others.”

She said there’s also room for improvement in infection-control practices at health care facilities.

“A lot of health care workers and health departments are working really hard at that, and it’s not easy to actually have good adherence and good compliance,” she said.

Highlighting areas for improvement with Candida auris will “help for the next emerging pathogen, whether it’s a virus or a bacteria or fungus,” she said. “Maybe by addressing Candida auris, we’re a little bit ahead for the next one.”

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.

For more stories on the Candida auris outbreaks, visit lvrj.com/superbug.