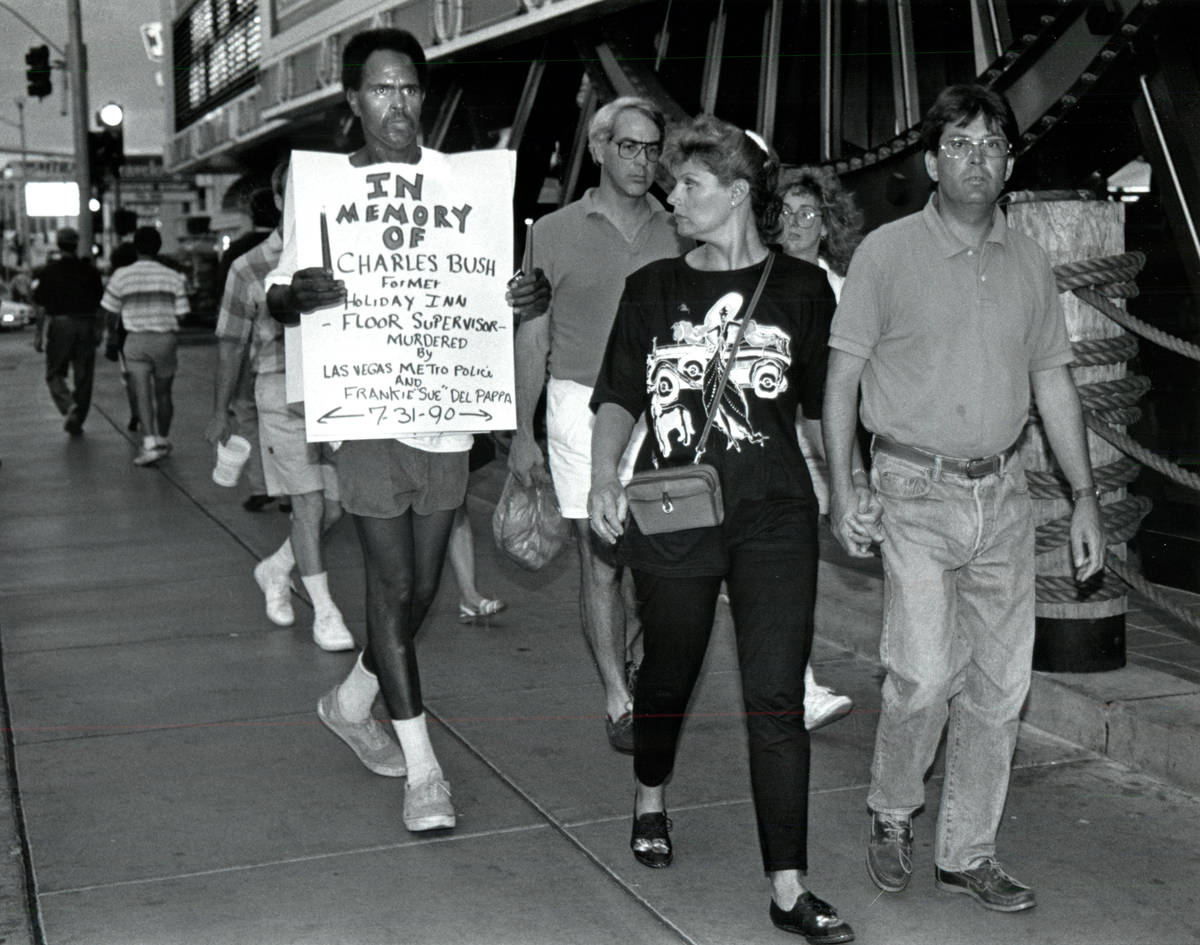

swelling crowd of protesters fills the streets, demanding a long-overdue racial reckoning in America.

“Enough is enough,” they angrily chant in unison, their signs bobbing up and down as they march. “WHO WILL DIE NEXT?” one sign reads. Another warns, “BEWARE OF BAD COPS!”

It is a sight of unrest that could be mistaken for any Black Lives Matter demonstration happening today in cities across the country, sparked by the Memorial Day killing of George Floyd, a Black man who suffocated as a white Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes.

But this scene isn’t set in present-day America.

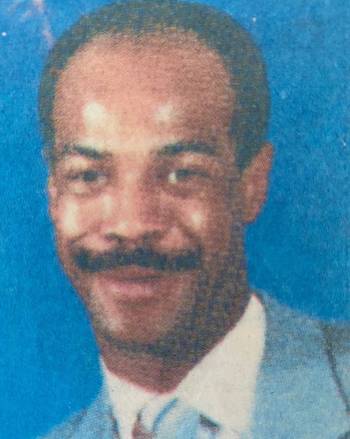

The year is 1990, and little more than a month has passed since Charles Bush, a 39-year-old Black man, was choked to death in Las Vegas shortly after three white Metropolitan Police Department officers entered his apartment without a search warrant as he slept.

His death, on July 31, would lead to a new state law, still in place today, setting limits on the use of chokeholds by police, and force top Clark County officials to reexamine a process known as the coroner’s inquest, a system meant to provide transparency in police shootings and in-custody deaths but criticized by some as being biased in favor of law enforcement.

But for all the change that his death inspired, the 30th anniversary of the casino floorman’s killing this month underscores America’s glacial pace toward dismantling and adequately addressing systemic racism in policing.

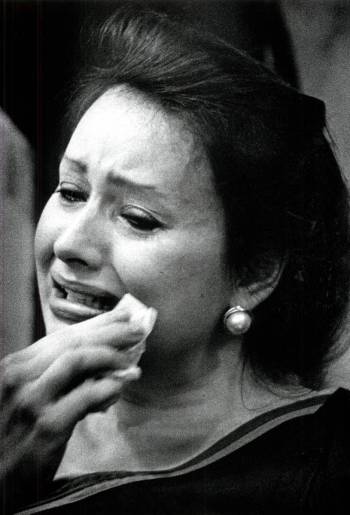

“What I don’t want is for us to be here in another 30 years saying the same thing — that nothing has changed from 30 years ago, and even 30 years before that,” Terri Siddoway, who was Bush’s pregnant girlfriend at the time of his death, recently told the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

Deadly encounter

Charles Jr. was around 12 when he learned how his father died. Siddoway explained to him that she stepped out of their apartment at the Paradise Resort Inn, sometime around 12:30 a.m., to buy a pack of cigarettes.

Bush would be dead less than an hour later.

“To a point, it shaped everything in my life,” Charles Jr., now 29, said of his father’s death in a sit-down interview this month in Oregon, where he was born and raised.

Under the dark sky that morning, a squad of six plainclothes vice officers was attempting to arrest prostitutes along Paradise Road, a known problem area for prostitution just east of the Las Vegas Strip, not far from the couple’s apartment.

Siddoway, who had once worked as a legal prostitute in Nevada, has said she accepted a ride from a stranger to the convenience store because her blistered feet were in pain. Police said otherwise.

By 1 a.m., after her arrest, three vice officers — Gerald Amerson, Thomas Chasey and Michael Campbell — entered the couple’s apartment, using Siddoway’s key, to conduct a follow-up investigation. The officers did not have a search warrant to enter.

Inside Room 409, at what is now a Red Roof Inn, Bush lay asleep naked in bed, his back turned to the door.

Siddoway has said she did not give the key to the officers, nor did she give them permission to enter the apartment. Police said otherwise.

Her arrest and Bush’s death occurred long before the existence of police body cameras, and long before cellphone video had become an everyday weapon of sorts for civilians in documenting police brutality and misconduct. So three decades later, the police remain in control of the narrative surrounding Bush’s final moments: He charged the officers, they say, and a struggle broke out.

“We still don’t really know what happened in that room,” Siddoway said. “After all this time, we just don’t know.”

After Bush was handcuffed and placed on the bed, according to Metro, he began wheezing and died before paramedics arrived.

“I had no choice but to hold onto this man,” Amerson, the officer who placed Bush in a chokehold, said two weeks later in his testimony during a coroner’s inquest. “He was like a crazy guy.”

Grand jury indictment

Bush’s official cause of death was strangulation, and it was ruled a homicide by the Clark County coroner’s office. The chief medical examiner at the time testified to that during the inquest. Still, the seven-member inquest jury ruled unanimously that Bush’s death was “justifiable,” marking the 44th consecutive justifiable verdict handed down in coroner’s inquests since 1976.

Two days later, then-District Attorney Rex Bell announced that he would not charge the officers. “I would destroy the whole integrity of this process if I overturned it,” Bell said of the coroner’s inquest.

The integrity of the process, which is no longer used today, was questioned anyway by top county officials. It was replaced in 2013, following years of discussions, with a new process called the fact-finding review, which is held only after the Clark County district attorney’s office already has made a “preliminary determination” that no charges will be filed against an officer.

Las Vegas police now may use neck restraint only when lives threatened

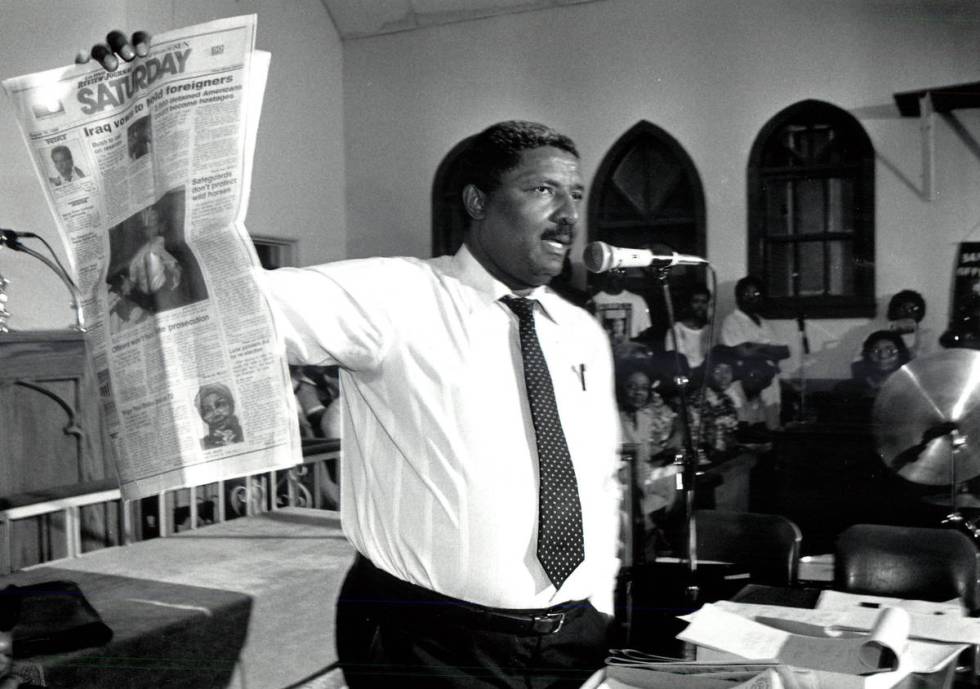

During the 1991 session of the Nevada Legislature, lawmakers had the chance to outright ban the use of chokeholds by law enforcement officers.

The bill, sponsored by then-Assemblyman Wendell Williams, was inspired by Charles Bush, who a year earlier had died after he was placed in a chokehold by a Metropolitan Police Department officer.

In his testimony at the time, Williams, D-Las Vegas, characterized the chokehold as a “license to kill.” The medical community largely supported his efforts in 1991.

By the time the Legislature met that year, it had been at least 15 years since the Police Department had conducted any sort of training on neck restraints, then-Metro Capt. Randy Oaks testified.

After fierce opposition by Las Vegas and Reno police, a watered-down version of Williams’ original bill was passed, permitting the use of the restraint as long as officers had received training. The law is still in place today.

“We know from medical research that it’s unsafe,” Williams said this month of the restraint. “You don’t know if someone has a preexisting condition. It’s just unfair, because at that point, when you use the chokehold, you become the judge, the jury and the executioner.”

Widespread conversation among community leaders and lawmakers about the controversial restraint resurfaced in 2017, after another Metro officer used an unauthorized, martial-arts-type chokehold on a man named Tashii Brown for more than a minute, killing him.

This month, Brown’s relatives reached a tentative agreement with Metro to settle a lawsuit for $2.2 million, surpassing payouts in Bush’s death. If finalized, it would be the largest settlement in the department’s history.

Both deaths — nearly three decades apart — resulted in the only two instances in the Police Department’s history of an officer facing charges in connection with an in-custody death. Neither case resulted in convictions.

Since Brown’s killing, Metro has repeatedly claimed that the department has never permitted the use of the chokehold.

Testimony from the 1991 Legislature contradicts that claim.

Oaks, the Metro captain, testified that use of the chokehold was left to the discretion of individual officers, according to news stories at the time.

“To foreclose the use of this hold by making it a criminal act is certainly overkill in this instance,” then-Metro Undersheriff Eric Cooper also said at the time.

Metro has said it only allows its officers to use a type of neck restraint technique known as the lateral vascular neck restraint. But that tactic is included in the state law’s definition of “chokehold.”

“I know Metro likes to play this semantics game, as I like to call it, and say, ‘It’s actually a different technique that does this or that,’” said Wesley Juhl, spokesman for the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada. “But it’s your arm around someone’s neck. It’s a chokehold.”

The permitted technique restricts blood flow to the brain by compressing the carotid arteries. Metro claims it is not the same as a chokehold, which restricts breathing.

At least twice since Brown’s death, Metro has made major changes to its use-of-force policy regarding the neck restraint.

In 2017, the department reclassified the tactic as an “intermediate or deadly use of force.” This month, following weeks of local Black Lives Matter protests in response to the death of George Floyd, Metro again updated its policy to say that the neck restraint could only be used in “life-threatening situations.”

Floyd, a Black man, cried out, “I can’t breathe,” as a white Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes.

Almost 30 years since the first chokehold bill was passed, Williams hopes to finally see a moratorium in Nevada on neck restraints following the 2021 session of the state Legislature.

“I was personally disappointed that people just didn’t get it back in ‘91,” he said.

On the national level, amid ongoing protests, congressional lawmakers are working toward one of the most ambitious policing overhauls in decades, including bans on chokeholds and no-knock warrants.

Unlike at coroner’s inquests, officers no longer testify during the new review process. And since its inception, not a single preliminary determination has been overturned following a fact-finding review.

“It is not a perfect process because the involved officers that caused the death of one of our citizens cannot be forced to testify,” Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson told the Review-Journal this month, adding that the process “is probably ripe for review to determine if any more improvements could be made.”

After Bell’s decision in 1990, the Nevada attorney general’s office stepped in, and the officers were indicted on charges of involuntary manslaughter and oppression under the color of office. A Clark County jury deadlocked 11-1 to acquit the men a few months later, and a mistrial was declared.

Then-District Judge J. Charles Thompson personally disagreed with the jury and said the officers had illegally entered Bush’s apartment. Thompson also said that had Bush survived and been arrested, he would have thrown out the case in court.

Amerson was fired in March 1991 by then-Clark County Sheriff John Moran, who since has died, and both Chasey and Campbell were demoted. Chasey left the department five years later, and Campbell retired in 2007. Amerson died in 2004 at the age of 74, and Chasey died in December at the age of 78. Efforts to reach Campbell for this story were unsuccessful, though public records indicate that he now lives in Arizona.

Twenty-seven years would pass before another Metro officer faced charges in connection with an in-custody killing.

Revised use-of-force policies

Black people make up just 12 percent of the population in the Las Vegas Valley, but on average in the last five years, according to Metro statistics, 32 percent of the people shot by police were Black.

Nationally, Metro has been praised as a model for police reform and transparency since 2012, when the U.S. Department of Justice opened an investigation into the department’s use of force in light of a Review-Journal series that uncovered examples of poor training within the department, a lack of clear policies and an unwillingness to discipline problem officers.

But for Metro, the years that followed the DOJ cleanup also have been marked by several high-profile killings of unarmed Black men, including the deaths of Tashii Brown in 2017 and Byron Williams in 2019.

A white officer shocked Brown seven times with a stun gun and punched him at least a dozen times before placing him in an unauthorized, martial-arts-type chokehold for more than a minute.

Williams, who was stopped for riding his bicycle without safety lights, told police, “I can’t breathe,” at least 17 times while officers pinned him on the ground using their hands and knees. A fact-finding review is set for Aug. 26.

Significant changes to Metro’s use-of-force policy, specifically regarding restraints that cut off the flow of oxygen and blood, came after both deaths. This month, following weeks of local Black Lives Matter protests, Metro again changed its policy on a certain neck restraint technique — this time only allowing its use in “life-threatening situations.”

The department previously permitted the neck restraint, known as the lateral vascular neck restraint, in any instance when an officer was confronted by “an assaultive person.”

“I don’t think reclassifying it is enough,” said Wesley Juhl, spokesman for the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada and a former crime reporter for the Review-Journal. “I think every cop knows what to say to avoid any accountability, and it’s just as easy enough for them to say, ‘I felt like my life was in danger.’”

The ACLU has long been at the forefront of local conversations surrounding police brutality and played a significant role in the aftermath of Bush’s death, calling for transparency and charges against the officers.

Metro did not respond to a request for an interview with Sheriff Joe Lombardo for this story, but at the time of the policy change the department issued this statement: “We are constantly evolving and looking for ways to improve our Use of Force standards. In this case, a national conversation about this technique showed us that we had room for improvement.”

In Las Vegas, there was outrage after Bush’s death 30 years ago. There was outrage after Brown’s death three years ago. And there was outrage after Williams’ death last year.

Each of the killings prompted local protests. None has resulted in convictions.

“My first reaction in reviewing Charles Bush’s killing was how eerily familiar it is,” Juhl said. “If you change some of the names, this could have happened yesterday. It’s the same thing: zero accountability, a district attorney that’s reluctant to act, questions about racial bias involving policing. It’s really sad that we haven’t made more progress.”

In 2015, 51 percent of Americans said they believed racial discrimination to be a “big problem,” according to a poll conducted by the Monmouth University Polling institute, a leading center for the study of public opinion on national and state issues. Now, five years later, that figure has jumped to 76 percent, a recent Monmouth poll found.

“George Floyd’s death was so blatantly wrong, I think it got everyone’s attention,” said Charles Hayes, an ex-Dallas police officer who went on to study bias in policing and write a book about it. “Now there are conversations happening that might not have ever taken place before.”

Kenneth Lopera, the officer who killed Brown, was initially charged in 2017 with involuntary manslaughter and oppression under the color of office. He was the first officer, since Bush’s killing, to be charged in an in-custody death. But Wolfson stopped pursuing charges against Lopera after a grand jury declined to indict him.

Thirty years ago, before Wolfson became the top prosecutor in Clark County, he was a criminal defense attorney who represented Amerson, the officer who choked Bush.

Asked whether his role in the Bush case could cast doubt in the community about his willingness to prosecute police officers, he told the Review-Journal: “It is nonsense to suggest that my office is not willing to prosecute law enforcement when we are currently prosecuting so many of them.”

He said his office, as of this month, was prosecuting 15 police officers for charges ranging from sexual assault and domestic battery to DUI and embezzlement.

“In my role as the DA, my responsibility is to prosecute persons where we believe it is warranted under the facts and circumstances of a particular case,” Wolfson said. “Police are no different than any member of our community in that respect.”

Leaving Las Vegas

A few months after Bush’s death, Siddoway was convicted of soliciting for prostitution, but she has long maintained her innocence.

She left Las Vegas that same year, in late 1990, to give birth and raise Charles Jr. near her family in a city in western Oregon.

“It was traumatizing — all of it,” Siddoway said. “It’s truly a miracle that he was born, seriously, because I hardly ate.”

For a long time, she missed Bush. They’d been together for about three years when he died. And maybe, she admitted this month, their relationship wouldn’t have lasted all these years, but their relationship’s end wasn’t Metro’s decision to make, she said.

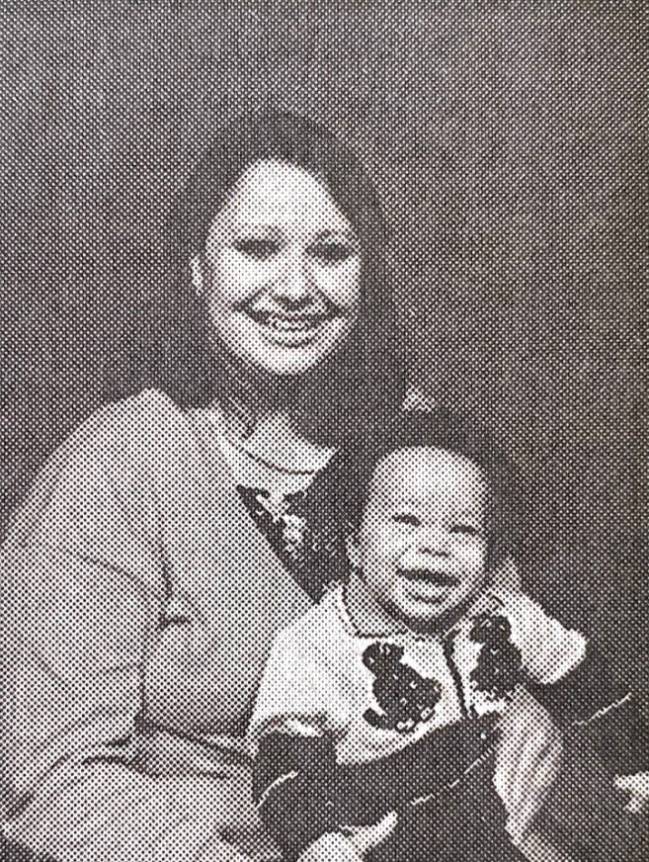

She still thinks of him from time to time. But how could she not, when her son is the spitting image of his father? Same eyes, same smile, same athletic gifts. Bush, who was 6-foot-6, was once a college basketball star. Charles Jr., an inch taller, was once a college football star.

Siddoway never married. In a way, she said, her youth was stolen from her the night Bush died. She was 31 at the time.

“My perspective on trust after Charles’ death is very different. That part of my life is long gone,” she said of dating. She paused, glanced at her son seated across from her, and added, “But I have a partner right there.”

Charles Jr. smiled.

Speaking up

In all, Metro paid out $1.1 million in settlements in Bush’s death. When Charles Jr. was 1, Metro settled a civil rights lawsuit filed on his behalf for $625,000. At the time, it was thought to be the largest Metro civil rights settlement.

Several months later, Metro settled a wrongful death lawsuit for $475,000 filed on behalf of Bush’s mother, Eula Mae Vincent, and his daughter, Angela Nicole Robertson, who was 17 at the time of his death. Vincent died in 2013, and Robertson could not be reached for this story.

The money for Charles Jr. helped pay for his private school tuition and sports throughout his childhood. It helped Siddoway build a better life for her son.

Still, Siddoway said, the money could never replace what was taken from him: a father and a Black man to look up to.

Charles Jr. was raised by a single white mom in Oregon, where the population is 87 percent white. He didn’t have Black friends growing up, he said, because usually, he was “the Black friend” in the group.

He’s lived his life toeing the line between black and white, constantly feeling like he never really fit in anywhere.

“That’s something he’s never admitted to me before,” Siddoway later told the Review-Journal.

Siddoway now works in the medical field and wants to advance her career. Maybe nursing school, she contemplates. In her free time, she shops at thrift stores and tends to her flowers outside her cozy one-story home, where she lives with Charles Jr., her aging father and a pit bull terrier named Prince.

Charles Jr., who uses his mom’s last name, was recently laid off from his job at a bar due to the COVID-19 pandemic. He didn’t finish college but promises his mom that he will go back to school.

They live a quiet, boring life, far removed from the city where their family member was killed by police — exactly how Siddoway envisioned their future 30 years ago. But the scars remain, so neither stays silent.

“It’s important to get out there and have our voices heard,” Charles Jr. said.

So on a recent Friday evening, a few weeks ahead of Bush’s death anniversary, Siddoway strolled down a sidewalk, the Oregon sun’s golden light washing over her porcelain skin.

Moving slower than the rest of the crowd, because of a bad knee that will soon need to be replaced, Siddoway joined in on the chants: “Black lives matter! Black lives matter!”

Even in this city, where Black people account for less than 2 percent of the population, protesters continue to show up in the hundreds more than a month after Floyd’s killing appears to have finally woken America up.

Contact Rio Lacanlale at rlacanlale@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0381. Follow @riolacanlale on Twitter.