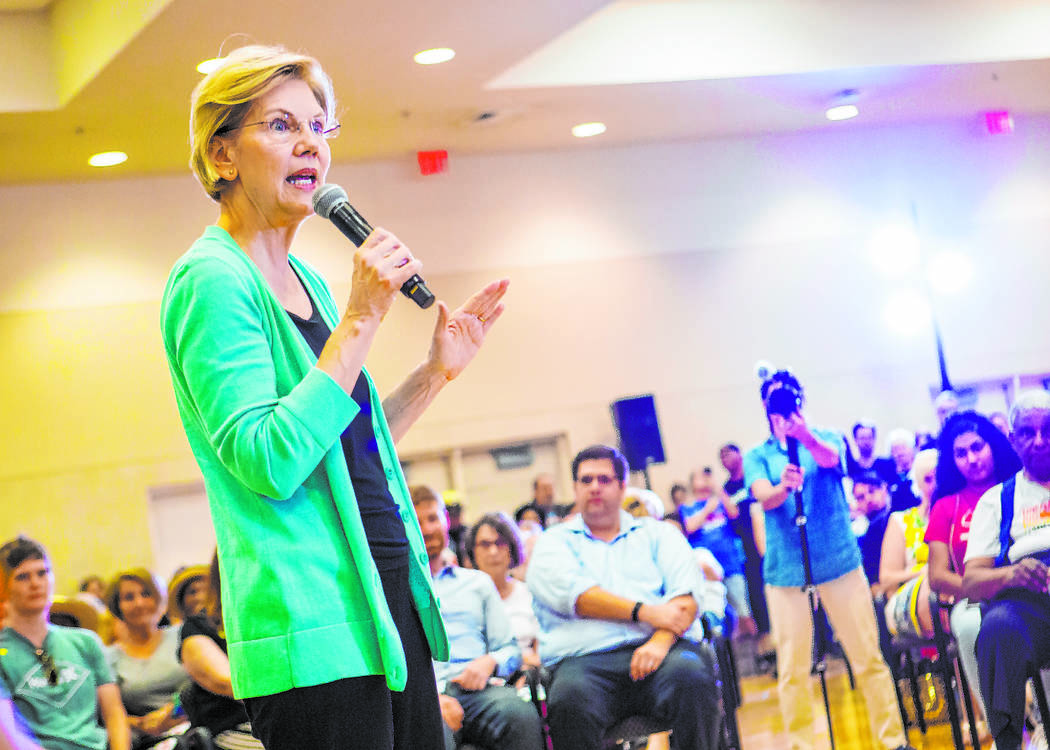

STEVE SEBELIUS: Warren’s war on the new Gilded Age

It’s obvious Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren isn’t going to appeal to everybody.

Warren, who visited Nevada last week on her latest campaign swing, is among the most liberal of the Democratic candidates seeking the presidency in 2020. Not only does she support much more vigorous regulation of big banks, she wants to break up big corporations and impose a 2 percent wealth tax on assets of more than $50 million.

Warren promises universal child care, universal preschool, universal health care and universal free community college, trade and technical school as well as public college tuition.

But no matter what you may think of her political views, Republicans and Democrats should be able to agree on the philosophy that undergirds Warren’s war on the new Gilded Age: the naked power of special interests over the government.

A recent New York Times magazine piece noted the odd similarity between Donald Trump’s call to “drain the swamp” and Warren’s disdain for the government’s subservience to the lobbying class that regularly peddles influence in order to advantage corporate America over smaller businesses and regular people.

It’s not to say they share the same idea: Trump seems to believe (like a skein of Republican presidents stretching to Ronald Reagan, from whom Trump appropriated the Make America Great Again slogan) that government itself is the problem. Warren, by contrast, believes government can do good for people, if only it’s insulated from corrupting influence.

But both protest the current state of the government — and with good reason.

It’s hard to argue with Warren’s call to, say, end private prisons when abuses in such facilities abound, including some of the detention centers where immigrants are being held near the southern border.

“I don’t believe anybody should be making a profit of off locking people up,” Warren told me in an interview. “You know, if we really believe people need to be locked up, then that is a government function and it should be run by the government.”

Ditto with her idea to ban former Cabinet members, senators and members of Congress from returning to lobby their ex-colleagues for pay.

“I think that when you work for the government in a position like that, you’re working for the taxpayers,” she said. “And no one in this country should wonder whether or not you’re looking … at the next job that’s going to pay you millions of dollars. For what? For your Rolodex, for access to who you know.”

That’s especially true because regular citizens and small businesses seldom have the resources to hire lobbyists to argue their case behind Washington’s closed doors.

The same goes for her assessment of the state of the overall economy and how government works well for big drug companies booking record profits, even as patients struggle to pay for their prescriptions. Or how so much wealth is concentrated in just a few hands at the top. Or should we believe the disparity exists because those elites are so much smarter, harder working and more naturally virtuous than the rest of the population?

Said Warren: “Understand, it’s not just something that’s happened in the last couple of years. It’s been going on now for decades, in which the rich and powerful just keep calling the shots, just keep day by day by day getting a little more power and doing a little better, while everybody else just gets left behind.”

Few people would be surprised to hear Warren talk about Roosevelt as her favorite president. But many might be shocked to learn she means Republican Teddy and not Democrat Franklin Delano. Why? Because Teddy Roosevelt took on the corporate monopolists of his day, just as Warren wants to take on big technology companies in hers.

Skepticism of large industry is hardly confined to a single person or party. Republican Dwight Eisenhower, a lifelong soldier, warned of the growing power of the military-industrial complex. He saw what Warren now sees: Powerful special interests bending government and regulators to their will, often at the expense of the public good.

Yes, regulation can go too far and stifle industry unnecessarily. Any freshman Republican congressman worth his or her salt can give you an example of that. But those regulations generally stem from the excesses, negligence or intentional wrongdoing of private actors rather than anti-business zeal.

So while Warren’s solutions might not appeal to everyone, the philosophy that drives her ideas cuts across party lines. In a polarized political world, there’s something downright refreshing about that.

Contact Steve Sebelius at SSebelius@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0253. Follow @SteveSebelius on Twitter.