Cajoling, bluffing are crucial skills for Clark County truancy officer

Tony Stark has a knack for detecting students who are skipping school.

He knows where kids go to smoke marijuana. He can tell if they’re about to make a run for it after seeing him pull up in his white Clark County School District van.

The street savvy comes from nearly two decades as an attendance officer, scouring the streets of Las Vegas during school hours to find students who are ditching class.

It’s a critical role, but one that comes with a heavy load.

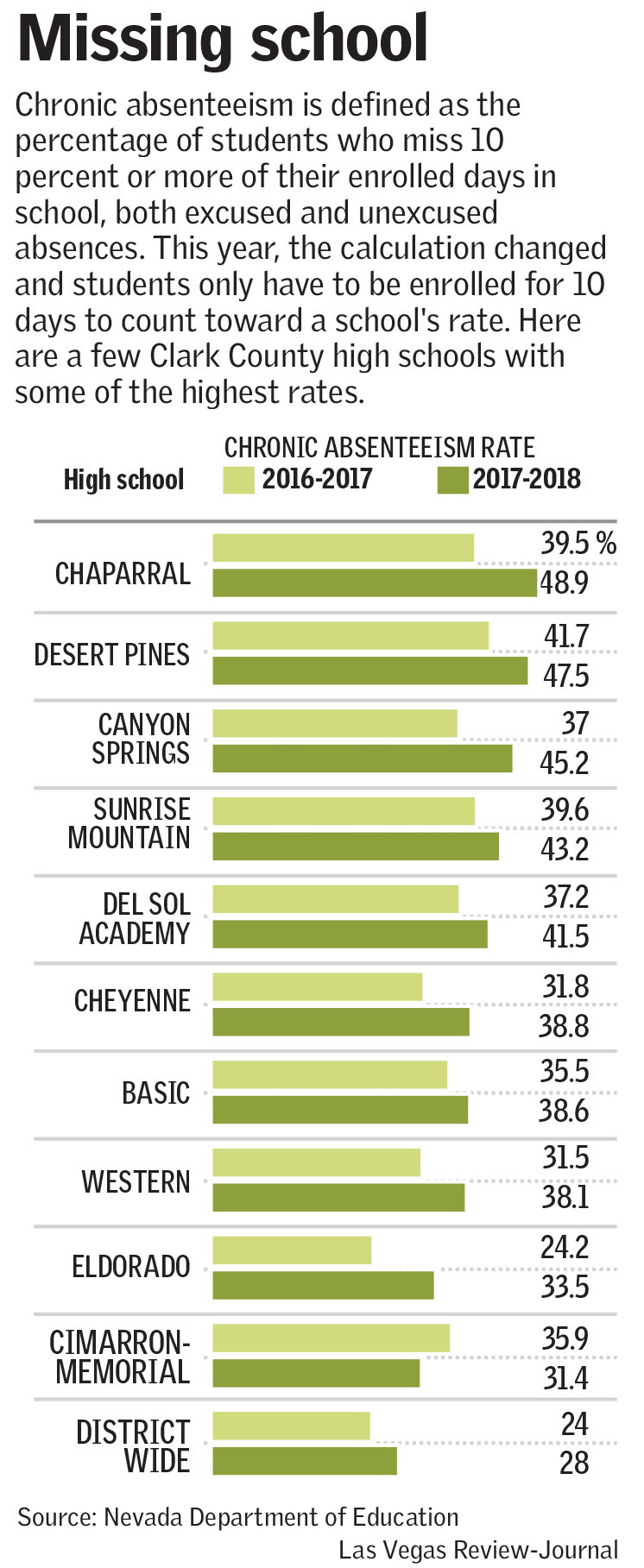

Chronic absenteeism in the district is on the rise — in part, perhaps, because the state recently changed the way it calculates the rate. That has consequences for schools, which are being held to a higher standard to limit the number of students who miss 10 percent or more of school days. Some are even losing stars in the state’s ranking system over it.

But Stark and many others who seek to enforce attendance argue that the problem is not just about numbers: Students know there are no real consequences for being truant and exploit that, they say.

Meanwhile, both the district and the juvenile justice system have been working to end the so-called school-to-prison pipeline — where juveniles who come into contact with the justice system for minor offenses often progress to more serious crimes and eventual incarceration. In this case, that means issuing fewer citations for truancy and attempting early interventions.

Stretched thin

It’s 10:20 a.m. on a recent Wednesday and Stark is pleading with a fourth-grader who hasn’t been going to school.

“Come on, man,” he says, standing in the doorway of the student’s Las Vegas apartment complex and trying to get him to Dailey Elementary. “You’re not doing nothing here.”

The boy’s mother had told Stark she’d simply given up. Her son just doesn’t like school.

It’s the last time Stark will make this house call. The next step: referral to Child Protective Services.

“OK, look,” he tells the boy after 10 minutes of fruitless coaxing. “You don’t go with me this time, or you don’t show up tomorrow, we’ve got to take it to a higher level.”

It’s a tough part of the job for Stark and the district’s 22 other attendance officers.

Some kids call him Iron Man — referring to the name he shares with the comic book character — but his powers are actually rather limited. He can’t step foot inside a student’s home. He can’t write citations for truancy. He can chase kids if he wants, but he doesn’t bother — it can be dangerous if a child dashes out into traffic.

All Stark can do is try to connect with the child.

And there’s precious little time for that. Stark is responsible for tracking down truants from 22 schools in the Winchester area, which stretches from the south end of the Strip east to Boulder Highway. It’s a high-needs, highly transient community that includes residents of numerous weekly-rental complexes.

His van serves as his office and is stacked with papers — each page representing a student identified as chronically absent by their school. He is required to perform an attendance check on each one, which typically means advising parents of attendance requirements.

But the paperwork piles up because he spends much of his day focused on other issues.

He transports sick students whose parents can’t pick them up. He warns parents who consistently fail to retrieve their children on time at the end of the school day. Once a week, he drops off clothes from Operation School Bell to schools with children in need.

Senior Attendance Officer Pam Foltz said the department should have one officer per 10,000 students. Over the years, it’s been one per about 18,000 students.

The addition of five more officers this year helped, she said, but it’s still not enough.

“We need more officers,” Foltz said. “If you want us to fight attendance, if you want us to fight truancy, I need the people in the field to do it.”

No teeth

Just after 1 p.m. that same day, Stark pulls up to four Valley High School students hanging out at Sterling Park apartments.

He’s a master at bluffing. In this case, he lies to the kids so they don’t run.

“If you go that way, somebody’s coming,” he says. “If you go this way, somebody’s coming.”

The freshmen giggle furiously as some of them lie to Stark about their names. Eventually they relent and admit they are ditching.

Then they pile into the van and Stark drives them back to school.

The encounter is an example of one of the biggest challenge’s in Stark’s job.

“Kids know that there’s no consequence, so they run rampant. They just do whatever,” he said. “… We can try to show our teeth and everything, but kids kind of know we only have so much.”

Stark recalls the days when he used to write truancy citations, which required the youths to appear in juvenile court. Now, only police officers can do so.

He also remembers seeing students locked up for being chronically truant when he worked at the Juvenile Detention Center.

But officials are attempting to prevent such relatively minor offenses from escalating to criminality.

Early intervention efforts

Schools may file for educational neglect with the state’s Division of Child and Family Services if absences continue for elementary students. That process, which requires extensive documentation, could lead to intervention by Child Protective Services.

Older students who end up in court for truancy could face fines, suspension of their driver’s license or community service. Yet that statutory punishment can be hard to enforce — families may not have money to pay the fines, for example, or students may not have cars.

These days the district attorney’s office rarely goes after truants — a truancy court, which used to handle such cases, ended around 2011.

Officials say that there were too many referrals to handle. Instead, they wanted to look at the root of the problem.

“All the statistics show that the formal court process for dealing with truancy is just not effective,” said District Court Family Division Judge William Voy. “Most of those issues can be resolved if you’ve got folks sitting down long enough to discover what those issues are, and then bring in resources.”

Now chronic truants can be referred to other services — such as the juvenile assessment center known as the Harbor — or less punitive programs, such as the Student Attendance Review Board or the Truancy Diversion Program.

“We’re trying to cut back on those citations and move forward on mentorship and ways to help households,” said Thomas Gerbracht, the district’s coordinator of attendance enforcement.

When families become disillusioned with the school, he said, all it takes is one mentor to invite them back and have that feeling of community again.

“Charging somebody into court does not give them a sense of community at a school,” Gerbracht said.

The diversion program, created in 2000, seeks to address the underlying reasons students aren’t attending school, and includes meetings with a volunteer judge, family advocate and other personnel.

An annual federal grant of $200,000 from 2014-2016 enabled the program to expand to 89 schools. But the number of participating schools has dropped to 49 now that the grant has ended, since schools must now pay for the $3,950 program.

Some on the front lines of the fight against absenteeism question the effectiveness of the gentler approach.

“Kids are not stupid,” said Foltz, the district’s senior attendance officer. “They know there is no truancy court. They know we have no teeth.”

New standards

A white board hangs in the front office of William Snyder Elementary to remind families of attendance goals.

The high-poverty school aims for no more than 30 absences total every day. On a recent day in October, the number stood at 69.

Principal Jenne Haynal said the school tries to tackle the reason why kids are missing.

“Is it that they’re not waking up? Do you need an alarm clock?” she said. “Sometimes the parents will say, ‘Well, he didn’t have any clothes.’ Okay, well, what’s the issue with that? Is it that you don’t have the clothes? Did they grow out of them? Do you need new clothes? Do you need laundry soap?”

Like other schools, Snyder is struggling with the change in the way the state Department of Education calculates absenteeism.

The state previously rated schools based on their average daily attendance, but now must count the number of students who miss 10 percent or more of the days they are enrolled. It does not matter if those absences are excused or unexcused.

In the 2016-17 school year, that metric only applied to students who were enrolled for at least 30 days at a school. But now, administrators are responsible for students who are on their books for 10 days.

That’s challenging for highly transient schools like Snyder because students who come and go in a few weeks can still count toward the absentee rate.

“When they first enroll and they miss a day or they miss two days, it doesn’t necessarily put up a red flag for you because a child that misses a day might have a cold,” Haynal said. “… they’ve only been enrolled for a handful of weeks. It doesn’t necessarily send up any warning signs. But then they withdraw.”

Students that officials can’t track down may only be withdrawn from the school after 10 consecutive absences, which also adversely affects the absenteeism rate.

Snyder Elementary missed out on reaching four stars this year, a goal it would’ve reached if it had not lost points for chronic absenteeism.

Haynal is trying to increase awareness among parents. Two days per month doesn’t feel like a lot, she said, but that makes a child chronically absent.

“We will do whatever it takes,” she said. “Including having a neighbor knock on the door every morning at 6:45 a.m. to make sure everyone’s awake.”

New hope

Diana Escobar didn’t see a point in coming to class.

The Chaparral High School senior was hardly ever in school during her freshman and sophomore year.

“At one point I just lost motivation,” she said. “I was just like, I really didn’t care.”

But her aunt and uncle intervened, warning her of the long-term consequences of dropping out. That talk resonated with Escobar and now she’s working to make up for classes and graduate on time. She’s even enrolled in an Advanced Placement anatomy class.

She regrets skipping as an underclassman, because she knows she could’ve had an easier senior year.

“I’m not struggling that much,” she said, “but it’s like a weight on me.”

That is the kind of outcome Stark hopes to engineer as he navigates the streets and apartment complexes of his beat. But even Iron Man can’t be in two places at once.

On a Thursday afternoon, he spots a student walking near Orr Middle School. But he’s taking a sick child home.

“You gotta freebie today,” he shouts as he drives by. “You know I’m going to catch you tomorrow.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.

Optional service

Another challenge for attendance officers: the district’s reorganization, which allows schools to determine whether or not they’d like to pay for an attendance officer from their own school budget.

Pam Foltz, the senior attendance officer, said that 35 schools so far have said they will not pay for attendance enforcement because they don’t use the service enough.

“What happens when we have that school that has a real emergency, a suicide ideation, a broken leg,” she said. “And now we’re not servicing that school because they didn’t provide for our services?”

Attendance review board

This year, the district expanded another truancy initiative as required by law — the Student Attendance Review Board.

The program allows schools to recommend chronically absent students for a truancy officer’s supervision throughout the year. The program previously had only one truancy officer until last year, when two officers worked with 16 schools total.

Now all 23 attendance officers are involved in the program, and every middle school may recommend three students for intervention. Eight high schools also are participating in the initiative.