Clark County schools try new approach to student discipline

Cindy Spencer didn’t have a great start to her time at Jerome Mack Middle School. After yelling and throwing something at a teacher — she doesn’t remember what — the 12-year-old ended up in the STEP classroom.

The STEP classroom, for Successful Temporary Education Placement, is almost a “school within a school.” It’s the main way Mack officials attempt to handle discipline in-house, rather than sending students to a behavioral school or banishing them through suspension or expulsion.

Under the patient tutelage of Candace Aplin — and after a few false starts — Cindy was able to improve her attitude and return to her regular classroom. Her disciplinary record is spotless over the five weeks since her return.

“It was hard and good at the same time,” Cindy said of her experience. “I wouldn’t have learned what I had learned in STEP (at home).”

The STEP classroom, now in its fourth year at Mack, is one example of how schools are using a Clark County School District grant program called HOPE2 (pronounced “hope squared”). The efforts vary in how they are set up, but they share a common goal: to move from a reactive disciplinary footing to a proactive approach that catches bad behavior early and prevents it from escalating.

Different approaches

Schools that apply for grants have some latitude in how they use them. Some opt for the “separate-and-rehabilitate” model being used at Mack, but others are trying other approaches.

Cheyenne High School operates a student-run tribunal to deal with lesser offenses. Bonanza High School has a dedicated staff member who works with students with histories of behavioral trouble and supports others who are experiencing issues impacting their learning.

But there are limitations to the programs. Some students don’t qualify for suspension or expulsion but have committed certain offenses where they’re disruptive to campus if they stay, said Dave Wilson, principal of Eldorado High School.

“I like having a HOPE2 program on our campus. I own my kids instead of putting them in behavior school,” he said. “But it’s not a panacea. It’s a fine balancing act.”

But HOPE2 programs, many of them fairly new, are creating success stories. Administrators say the instructors and counselors working in the program are forming relationship with students, setting expectations and changing culture, all of which takes time.

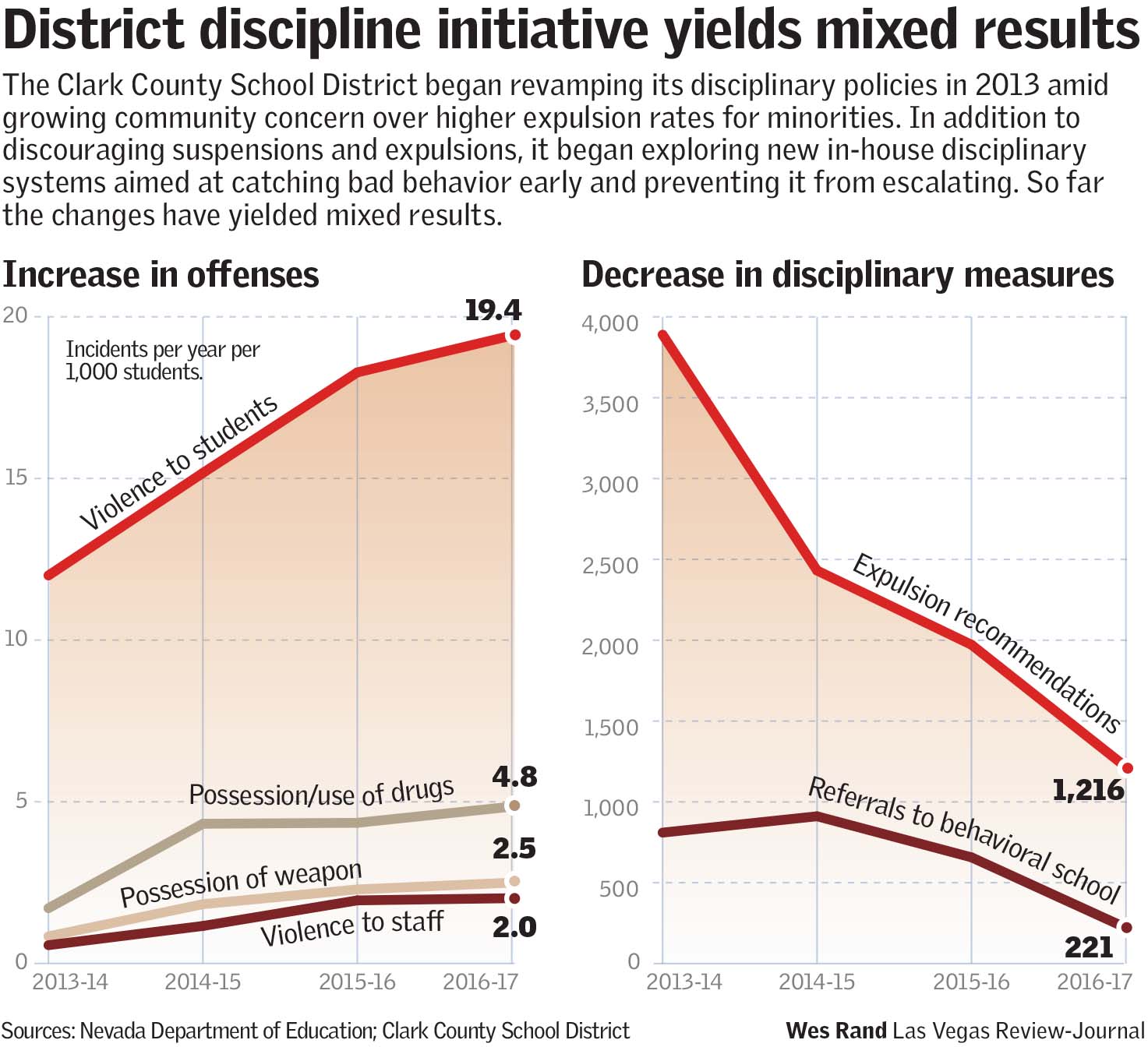

Districtwide, the results of the experiment have been mixed. Suspension and expulsion rates have dropped dramatically over the last three years, but overall violence in schools is up.

But Cheyenne officials say its grant-funded tribunal, now in its second year of operation, is generating promising early results.

The system works like this: When students are disruptive or disrespectful in class, teachers refer them to the dean’s office. The dean handles serious cases that may lead to suspension or expulsion, but lesser infractions are referred to the tribunal. It hears the cases and recommends disciplines, though adult staff make the final decisions.

Few repeat offenders

In its first year, the tribunal handled 434 cases. Only three of those students became repeat offenders, according to counselor Regina James and Gerald Robinson, the school’s social worker.

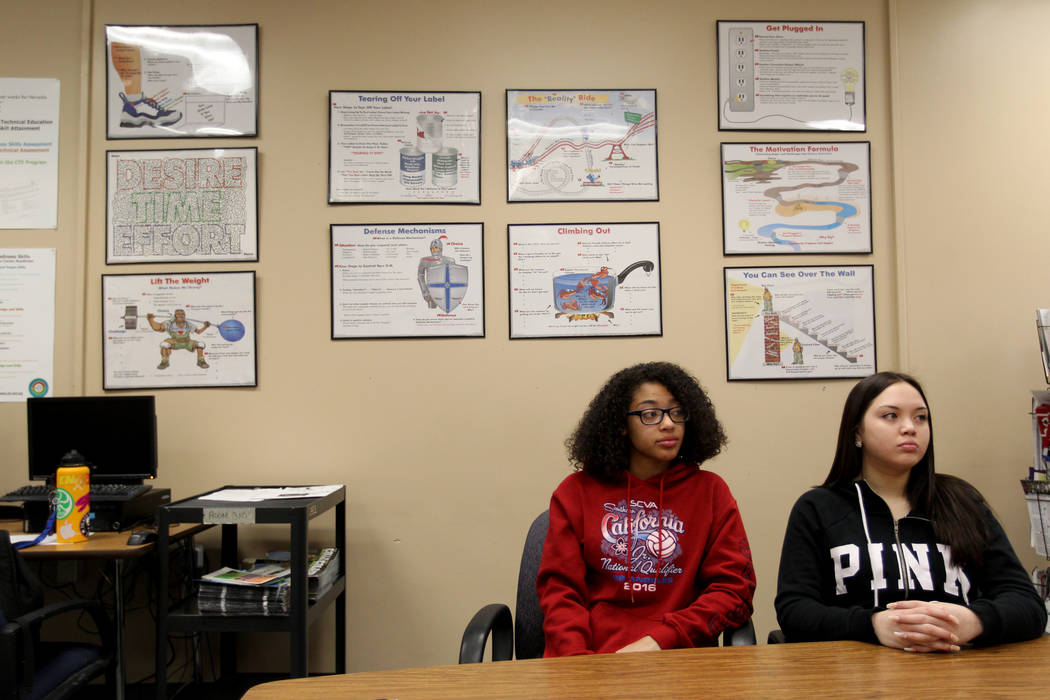

Right now, 16 students are trained to sit on the tribunal. They were selected for their leadership abilities. Miya Burns, a 17-year-old junior, is also the varsity volleyball captain. Alanna Keen, 16, is the junior class president.

The students, usually a panel of three, open the session with the offender — called the participant — with an icebreaker, as a chance to connect and find common ground.

James or Robinson will lead the participant through a set of questions, including having the student explain what happened, how it affected them and other people around them and what they think the solution is.

After that, the tribunal members usually settle on an appropriate punishment after discussions with James or Robinson. Most often it’s a written apology that the student reads in front of the class.

The system can also provide support for students in other ways. As a social worker, for instance, Robinson can help address problems at home that find their way into school.

While the tribunal might conjure up images of the Spanish Inquisition, students who serve on it say offenders usually don’t bear any resentment afterteward.

“They see me in the hallways, they say, ‘Hi,’” Miya said.

Minutes instead of days

At Bonanza, a classroom across from the main office is outfitted with a treadmill, a couch and ample art supplies and board games.

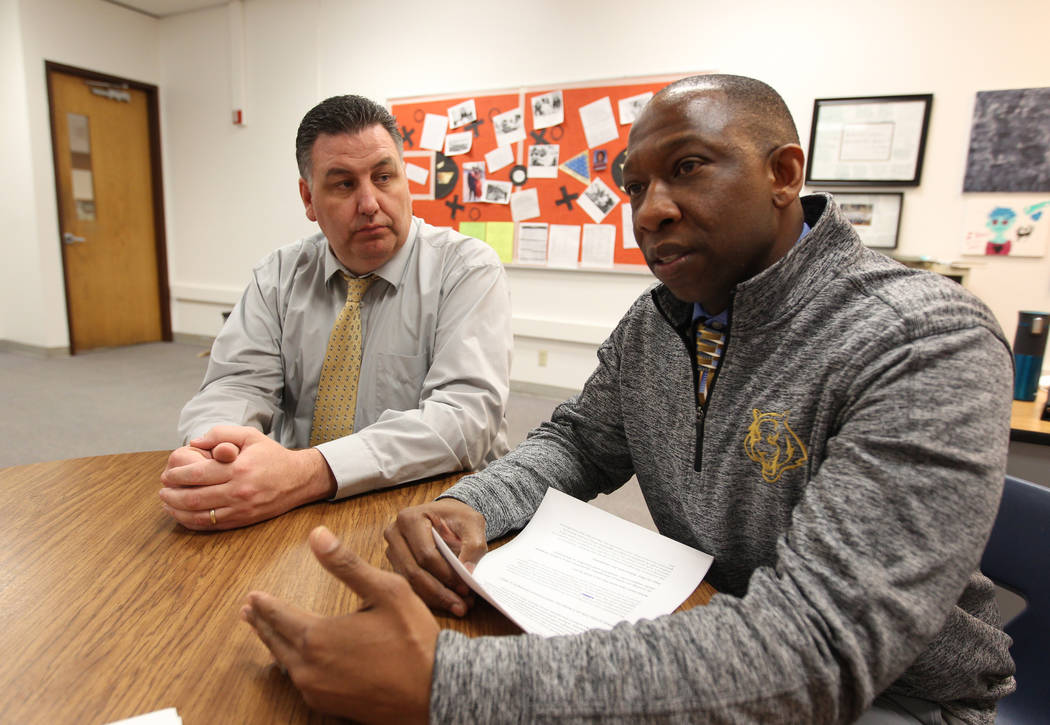

Jermone Riley, the school’s behavioral strategist, wanted it full of ways to help kids blow off steam and avoid confrontation. His position is partially covered by the HOPE2 funds, and the rest is covered in the school’s strategic budget. In three years, he’s become an integral part of the campus, principal Joe Petrie said. Riley previously worked at one of the district’s behavioral schools, so he’s well-versed in dealing with difficult students.

Students who are struggling can pop into his room, with the permission of their teachers. Bonanza Principal Joe Petrie endorses the impromptu visits, saying it’s better to miss “15 minutes now instead of a three-day suspension.”

Once they’re there, Riley tries to uncover what they need to get back into a learning frame of mind. Sometimes it’s a bottle of water or food, because they didn’t get any at home. Sometimes they nap on the couch after working late and getting up early for school.

Whatever it takes.

“I connect the dots,” he said. “I’m the bridge on campus.”

Riley also mediates conflicts between students or between students and teachers. He chats with any student who comes through his door and regularly meets with and mentors some students.

That includes a group of 15 freshman boys. Prior to attending Bonanza, each had multiple suspensions, expulsions or stints in a behavioral school. Only two have had a disciplinary issue this year.

A multi-tiered system

At Mack, the STEP classroom is one of the most severe measures for disciplinary infractions. There are lesser measures. Teachers attempt to handle issues in classrooms, and sometimes can. They’ve also got a ten-minute zone, called the TMZ classroom. Administrators will conduct meetings with parents.

Principal Roxanne James brings her therapy dog, Wrigley, to school to help calm student nerves.

Sometimes that’s not enough, though, and students land in Aplin’s classroom.

Mack is an all-digital school, so each student has a laptop and can keep up with their studies while working through the behavioral issues that landed them there.

“Every day is a new start,” Aplin said.

Students spend as few as 10 days in the STEP program or up to nine weeks, depending on the severity of their infraction and how they respond to one-on-one coaching. But Aplin can keep them longer or, if they’ve made enough progress, send them back early.

Administrators say they have seen change.

“They may have issues in the neighborhood, but they don’t fight here,” said Assistant Principal Rhonda Calvo.

Contact Meghin Delaney at 702-383-0281 or mdelaney@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MeghinDelaney on Twitter.

A different approach

The Clark County School District began changing its disciplinary culture around 2013, amid growing community concern over higher expulsion rates for minorities. In 2015, it also faced a complaint filed with the U.S. Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights on the same issue.

The district first changed protocols to reduce the overall number of suspensions and expulsions, limiting when a principal can recommend expelling a student. A student who commits battery on a school employee, sells controlled substances or possesses a weapon must be expelled, per state law. CCSD also mandates expulsion for battery to another student with significant injury and second-time use or possession of drugs or alcohol.

In 2014-15, the district began closing most of its behavioral schools. Money from the behavioral schools is now allocated as grants to the middle and high schools through the HOPE2 program, allowing schools to explore different approaches to student discipline.